Saint Paul’s, the Antwerp Dominican church, a revelation

The Chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

of the Holy SacramentIn Christianity, this is a sacred act in which God comes to man. Sacraments mark important moments in human life. In the Catholic Church, there are seven sacraments: baptism, confession, Eucharist, confirmation, anointing of the sick, marriage and ordination.

and of the Sweet Name of Jesus

The AltarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine. with the

Ecclesiastical Dispute of the Holy Sacrament

(P.P. Rubens, ca. 1609)

Ca. 1609 the Dominicans ordered this altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. and the two predella pieces Moses and Aaron from P.P. Rubens. As a result of the new choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. rood loft with two side altars, the Baroque Sacrament’s Altar was built by Pieter Verbruggen in 1654-1656. Due to of aesthetic (and other?) motives the new altar – according to contract – was conceived as a counterpart of the opposite Mary-altar, which had been initiated four years earlier. To fit neatly into this portico altar Rubens’ panel was enlarged in 1680, especially at the top and bottom, as well as slightly in the width (up to 377 x 246 cm / 12.37 ft x 8.07 ft).

In 1616 the painting was entitled ‘The reality of the Holy Sacrament’, in other words: The real presence of Christ in the Holy Sacrament. The term ‘dispute’, derived from Italian, by which this painting is known, must not be interpreted as a discussion because of a difference in opinion, but rather as a colloquium among like-minded Catholics looking for arguments to back up this point of doctrine concerning the EucharistThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live.. That it does not concern a pious worship of the Sacrament, but an intellectual dialogue, characteristic of the scholastic tradition, is made clear by the gesticulations of authorized scholars and ecclesiastical office holders: “fingers are being raised, are pointing, emphasizing, refuting and summing up the arguments”. The mannerist, slightly elongated figures are typical of Rubens’ early period.

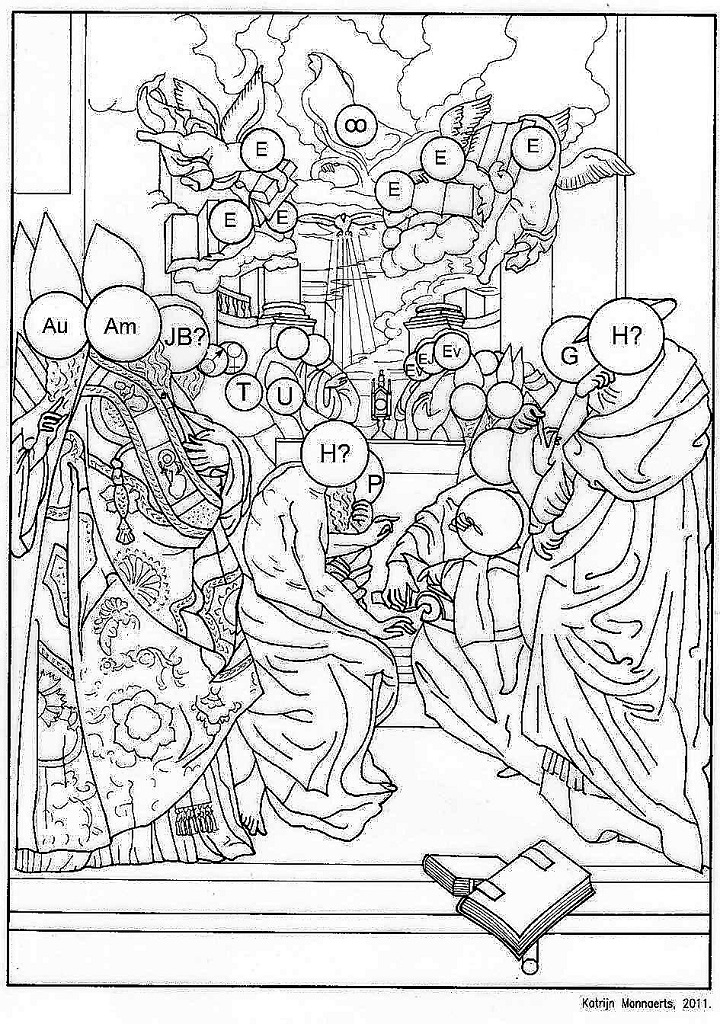

God the FatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. (∞), in heavenly soft shades of white, rosy and yellow, and the dove, symbol of the Holy Ghost, in the upper register emphasize Jesus’ real presence in the consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words. hostA portion of bread made of unleavened wheat flour that, according to Roman Catholic belief, becomes the body of Christ during the Eucharist..

Frisky little angels (E) hold open the Books of the Bible, showing phrases from the New TestamentPart of the Bible with texts from after the birth of Jesus. This volume holds 4 gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, 14 letters of Paul, 7 apostolic letters and the Book of Revelation (or Apocalypse). that give evidence to the actual presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, but in order to allow the spectator to read the text from a large distance, only one syllable a line has been depicted.

On the far left: “Caro mea vere est cibus, et sanguis meus vere [est] pot[us]” (= John 6:56; He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood abides in Me, and I in him.) In the centre this is paraphrased both left and right: “Hoc est corpus meum, quo pro vobis datur” (“This is My Body, which is given for you.). And on the far right: “Accipite et comedite: hoc est corpus meum” (Matthew 26:26-27: “Take, eat; this is My Body.”

Moreover Rubens accentuates this point of doctrine by the composition and the colours.

Moreover Rubens accentuates this point of doctrine by the composition and the colours.

The rhombic composition must create a tension around the white host, which, set in a gothic cylinder monstranceA decorated glass holder on a base, in which a consecrated host can be placed for worship. In general, there are two types of monstrances: the ray monstrance and the tower monstrance, with the name referring to the shape of the object. The tower monstrance is very similar to the reliquary, which was very popular before the adoration of the Blessed Sacrament became widespread., not only stands in the iconographical centre of interest, but was initially, before the enlargement of the panel in 1680, the formal centre as well.

The supernatural dimension in the tangible Holy Sacrament is stressed because the white host is marked off against the heavenly, blue middle section.

This blue colour is accompanied in the colour composition by both figures in the foreground: on the left in a golden cope, on the right in cardinalIn the Roman Catholic Church, a cardinal is a member of the pope’s council and thus he has an important advisory role. Up to the age of eighty, the cardinals also elect the new pope. Most cardinals are also bishops, but this is not a requirement. red. Thus the three primary colours are neatly divided in a triangular pattern.

At the time of the Counter Reformation the Catholic Church wanted to build and defend its views, also concerning the Eucharist, against the Protestants by calling upon authorized theologians from the unsuspected, early ages of Christianity. That is why the four great western Fathers of the Church come to the foreground. The two bishops on the left , in golden damask copes are Ambrose (Am), in the front, as the elder one who turns his head towards the second one, his pupil Augustine (Au) behind him.

As their full counterparts we find on the right a cardinal, possibly Jerome, in a cautious pose, and a monkA male member of a monastic order who concentrates on a life of balance between prayer and work in the seclusion of a monastery or abbey. in a black Benedictine habitGeneral name for the typical clothing of a particular religious order.

A long-sleeved, unbuttoned robe down to the feet, usually with a hood attached. This attire is typical of monks and nuns.

, possibly Pope Gregory I The Great (G?), who at first was the founder of a monasteryComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. and abbotThe man who has been chosen by the abbey community of which he is a member to lead that community for a fixed period.. But if he is accompanied by an old holy man who is half-naked (H?), that must be Jerome as a penitent in the desert, who always has a cardinal red mantle with him. In that case the cardinal on the right would be the scholar Saint-Bonaventure. Could the black-haired man behind Ambrose be identified as John the Baptist, who in the desert was not at all concerned about a delicate appearance and pointed out Christ as the “Lamb of God” (the pre-eminent term of address for Jesus, as present in the host of the Holy CommunionThe consumption of consecrated bread and wine. Usually this is limited to eating the consecrated host.)? Behind the half-naked man, the man with the long bald head, pulls his beard thoughtfully, and takes notes; he bears a strong resemblance to Saint-Paul (P).

In that case his writing activity refers to the oldest explanation of the Last Supper and to the oldest formulation of the Eucharist, namely in his First Letter to the Corinthians (11:23-39). The Pope, wearing a golden tiaraA triple crown: a headgear consisting of three crowns placed one above the other. It was worn by popes at official, non-liturgical ceremonies from the beginning of the 14th century until 1964, when Pope Paul VI renounced his tiara in order to sell it in favour of development aid., is Urban IV (U), who through the agency of the Liège beguineMember of a community of unmarried women who led a religious life and lived in a beguinage. Beguines took only two (temporary) vows: obedience (to the Grand Mistress of the beguinage) and purity. As they did not take a vow of poverty, they were allowed to own property. They also had to be self-supporting., SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Juliana of Cornillon (♀) behind him, established the feast of the Holy Sacrament in 1264: ‘Corpus Christi’. He is engaged in a conversation with the great Domincian theologian Thomas Aquinas (T), whom we recognize by the golden beaded garland at breast height. Among the other clergymen in varying habit, there is still another Dominican. The beardless young man in a toga, (dressed in red) is John the Evangelist. Both his neighbours are probably evangelists as well.

In 1794 the French Revolutionaries carried Rubens’ painting along to Paris as spoils of war. in 1815 the altar piece returned to Antwerp, in 1816 to its original spot.

You can study this painting in detail via this link.

- Saint Paul’s Church

- History and description

- Introduction

- Historic context

- The building history

- Saint Dominic

- Saint Paul

- The tower

- The architecture

- Floor plan and legend

- The sanctuary

- Chapel of the Holy Sacrament

- Our Lady’s chapel

- The mysteries of the Rosary

- Sermon, confession, music

- The mural paintings

- The treasury

- The Calvary garden

- Veemarkt gate

- Dominican pastoral activities

- Dominican convent

- The paintings in the cloisters

- Holy Cross Chapel

- SPK The weekly chapel

- Bibilography