Saint Paul’s, the Antwerp Dominican church, a revelation

The cycle of Paintings The Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary

The SORROWFUL MYSTERIES

The first Sorrowful Mystery

GETHSEMANE

(David I Teniers)

After the Last Supper Jesus and the three favourite apostles – Peter, John and James the Greater – go to Mount Olivet to pray in Gethsemane. In this nightly hour He experiences his death agony. We can read the fear in his eyes (Math. 26:37-38): “FatherPriest who is a member of a religious order., if you are willing, take this cup from me; still, not my will but your be done” (Lk. 22:42). John is lying asleep on Peter’s shoulder, James is sleeping in a sitting position. The moon breaks through the darkness of the night. In the foreground the light falls on everyone’s clothes. Judas and “a band of soldiers and guards with lanterns and torches and weapons” (John 18:3) enter the estate through a high gate. This panel was donated by Mrs. Vloers, a widow.

The second Sorrowful Mystery

THE FLAGGELATION

(P.P. Rubens, donated in 1617)

After having been sentenced to death by the Sanhedrin and the accompanying approval of the Roman governor Pontius Pilate to have Him crucified, Jesus is first flagellated (Math 27:26; Mk 15:15). Christ is standing with the wrists tied to the flagellation column. Rubens deliberately has Christ turn his back – in a twisted movement – towards the spectators. With this exhibition of the torturing he wants to move the spectator into compassion and through the emotions he wants to enhance the devotion to the Saviour. The colouring is meant to contribute to this emotional appeal as well. In contrast with the gloomy cellars of Pilate’s palace and the dark clothes of the executioners, the naked and bloody body of Christ is illuminated all the better. Rarely has the physical suffering of Jesus been portrayed so lively and so directly. Rubens tries nothing less than a director who pictures Jesus’ Passion in a raw film by focusing for minutes on the gruesome fate of the innocent man. One can see strips of skin being torn off and blood splashing around. While in a film the drama is raised by the slashing lashes one hears zipping through the air and by hearing them hit the tortured victim, Rubens has to stick to merely pictorial means.

The executioner in the foreground on the left is about to lash out again, with his arm that seems to come out of the frame. This movement also strengthens the power with which he goes for the victim.

Two brawny brutes, on the right, set about Jesus’ back with a rod. The black one in front is about to hit him firmly, holding the raised rod in both hands. As if this were not enough Jesus is kicked in the calves by him, to make him – literally – buckle under, while the soldier pulls away Jesus’ white loincloth in order to expose him even more to the lashes. “Surely he has borne our grieves and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted.” (Isaiah 53:4), thus the second reading on the Wednesday of the Holy WeekThe week before Easter, which begins with Palm Sunday. In that week there is also Maundy Thursday and Good Friday. It ends with Holy Saturday..

The executioner’s assistant in the back, stripped to the waist, seems to turn his eyes away and to screen his head: can he no longer bear to watch this horror, or is he trying to protect his face from the drops of blood spattering around? Or is he wiping the sweat from his forehead in order to insinuate the efforts he has taken to acquit himself of his diabolic task? On the right below a dog is watching fiercely.

Apart from a few adjustments of the composition, several details are also different from the oil sketch (Ghent, Museum of Fine Arts).

Donor: merchant Louis Clarisse; his son Mark Antony entered the Preachers in Antwerp.

The third Sorrowful Mystery

THE CROWNING WITH THORNS

(Artus de Bruyn)

In the palace of governor Pontius Pilate Jesus is cruelly mocked as “the king of the Jews” (Math. 27:27-31; Mk. 15:16-20; John 19:2-3).

Christ, exhausted from the slashing flagellation, has a crown made of thorn-bush put deeply onto his head, so deeply that blood is streaming abundantly from the wounds. Moreover, the reed cane which the soldiers “kept striking His head with” (Mk. 15:17), is here put into His right hand as a (broken) sceptre. The third attribute of the mocking, the purple mantle (Mk. 15:17) can hardly be seen, but is hanging from the bench, full of blood.

Faithful to the Bible, the protruding tongues of both the executioners with their grotesque mugs, represent how they spat on Jesus (Math. 27:30). In the foreground, the half-naked executioner kneeling in front of Him to pay Him tribute (Math. 27:29c; Mk. 15:19), makes an obscene gesture in front of Jesus’ eyes while holding a red cloth in his right hand, probably destined to strike him in the face” (John 19:3).

The composition and the position of the individuals, especially Christ in profile and the mocking kneeling executioner, go back to Albrecht Dürer’s ‘Scenes of the Passion’ of ca. 1510. However much the figures with their vigorous musculature may contribute to the spatial volume, the compact arrangement of the personages in the foreground remains flat. The slant eyes are typical of De Bruyn as well.

The fourth Sorrowful Mystery

BEARING OF THE CROSS

(Sir Anthony Van Dyck, ca. 1617-’18)

This is one of the earliest works by Van Dyck: he was not yet 20 years old. Of none of his paintings there are so many sketches. No fewer than 10 have been kept, which provides for an exceptional documentary on the history of the creation of a baroque tableau. Whereas he was too much self-centred in his first sketches, Van Dyck gradually discovered his position in the structure of the cycle. The originally horizontal composition evolved into a vertical one, while the original movement towards the left changed into a movement towards the right, as a result of the coherence with the chronological reading of the entire cycle. Because it shows a screened pattern, the drawing in the Antwerp Print Room is considered to be the actual modello. Nevertheless the poses of some figures were still adapted in the process of the construction of the painting.

This is one of the earliest works by Van Dyck: he was not yet 20 years old. Of none of his paintings there are so many sketches. No fewer than 10 have been kept, which provides for an exceptional documentary on the history of the creation of a baroque tableau. Whereas he was too much self-centred in his first sketches, Van Dyck gradually discovered his position in the structure of the cycle. The originally horizontal composition evolved into a vertical one, while the original movement towards the left changed into a movement towards the right, as a result of the coherence with the chronological reading of the entire cycle. Because it shows a screened pattern, the drawing in the Antwerp Print Room is considered to be the actual modello. Nevertheless the poses of some figures were still adapted in the process of the construction of the painting.

Several scenes of the Stations of the Cross have been merged here into one representation.

Jesus yields beneath the Cross. Executioner servants and a soldier make Jesus rise and go on. They pull the rope around His waist, urge Him with an ash stick and help to lift the crossbeam.

The meeting with His mother Mary. As Mary’s face is almost completely hidden in her intensely blue cloak – with lapis lazuli as its pigment – the emotion of her mother’s heart can be derived from the tense expression, the tears and her position, with bowing knees. Jesus’ look without words, looking behind at his kneeling mother, speaks for itself.

Thirdly, there is the help that is offered by the summoned Simon of Cyrene, in eye-catching bright red clothes behind Mary, by carrying the cross with Jesus.

The lances and halberds, which are lost in the gloomy sky of the background, emphasize the contrast between the display of power of the authorities and the inhuman grief of ‘mother and child’.

Apparently the painting was appreciated well, and was inspirational for many a painter. But this coin has another side as well. The painting was shortened both at the top and at the bottom with approximately 3.15 inches because later in the 17th century it was placed on the Holy Cross AltarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine.. In 1794 it was transported to Paris, to return here, after the French defeat, in 1816.

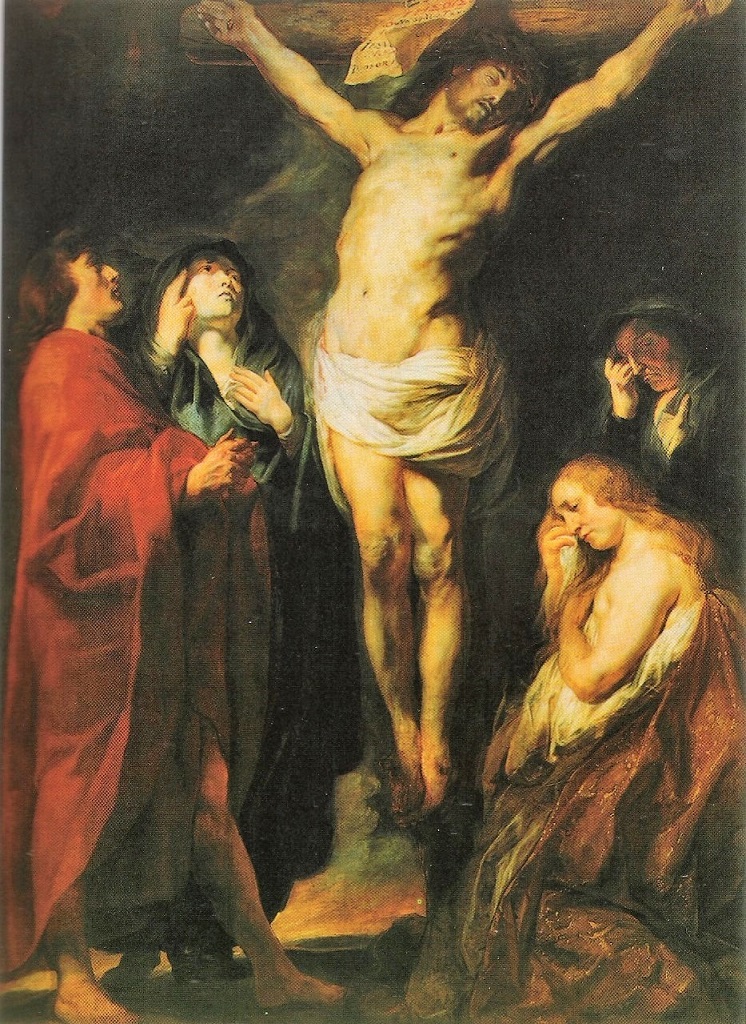

The fifth Sorrowful Mystery

THE CRUCIFIXION

(Jacob Jordaens)

Jesus, nailed to the cross, has already expired. Jordaens cannot refrain from using the ‘detail vivant’ so typical of Rubens, and has the parchment heading blowing in the wind. The four attendants, according to John 19:24-26, are placed neatly and parallelly at the left and the right sides of the cross.

Ichnographically on the right side of the cross we find Mother Mary and John the Evangelist. In desperation Mary raises one hand: “Why for goodness sake?”

On the left side of the cross Mary Magdalene kneels down, sobbing. Possibly the presence of her holy namesake was the reason for Magdalene Lewieter to donate this painting. Behind her there is Mary of Clopas, her eyes shut, her head bowed and resting on one hand in contemplation.

That the horizon nearly sinks on to the bottom frame is an ichnographical representation of the Biblical location, Mount Golgotha, from which one looks down.

The scientific justification of the data concerning the Mysteries of the Rosary in SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Paul’s in Antwerp can be found HERE.

It is basically written in Dutch, but using the translate button you can ask for an instant translation in English