Saint Paul’s, the Antwerp Dominican church, a revelation

No convent church without a choir

A proper high altar

History

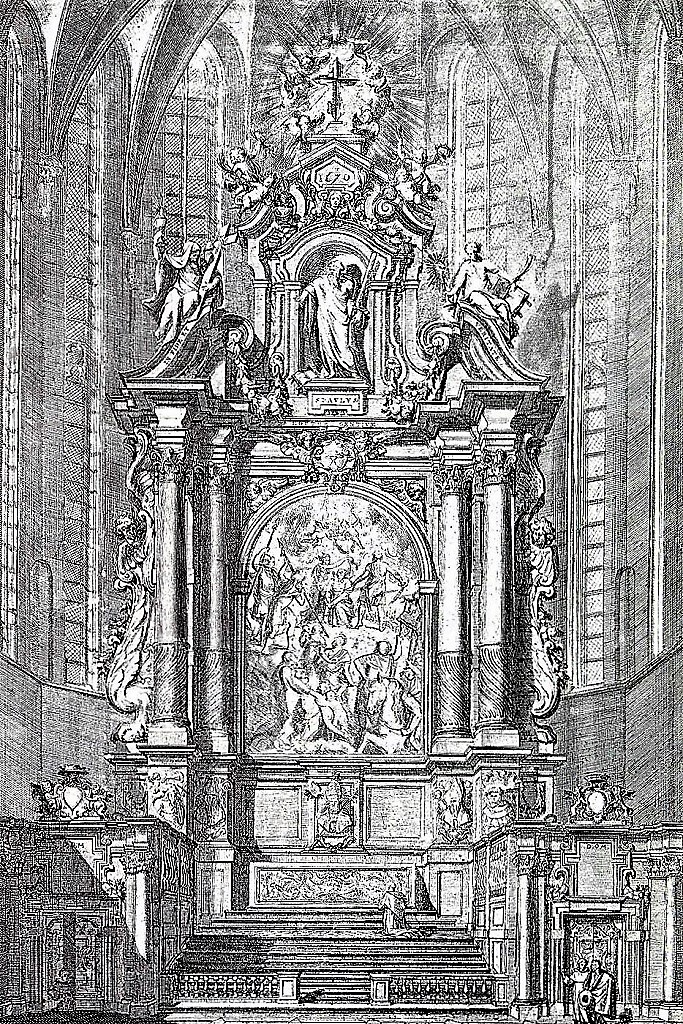

The eye catcher of the entire church, but originally only of the choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir., is the triumphant high altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine. (1670), which closes off the apseSemi-circular or polygonal extension where the high altar is located in a church. like a gigantic screen.

On the former high altar “SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Dominic’s vision” by Rubens figured, which can be dated stylistically ca. 1618-1620. Dominic is said to have had a vision in which he saw himself and his friend Francis of Assisi protect the sinful world against the wrath of Jesus. In line with the three worst sins man can be tempted by – pride, lust and greed – Jesus shoots as many lightnings. Upon this Mary tries to calm Him down. She proposes two loyal servants to Him, who can convert the world: Saint Dominic and Saint Francis. By this altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. the attention of the Dominicans in the choir stallsA series of seats, usually in wood, along the long sides of the choir. These seats are reserved for those who pray and sing the choir prayers. was permanently drawn to their mission: to follow the footsteps of the founder of their order by mediating the Saviour’s divine mercy for humanity.

The marble portico altar

The Dominican and former prior Marius Ambrosius Capello, bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’. of Antwerp, wanted to bequeath to his conventComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. an unforgettable present: the marble portico altar, up high in the sanctuary. The then prime cost of 80,000 guilders is the equivalent of no less than 3.8 million Euros today. The colossus, designed by Ambrosius’ private chaplain Frans Van Sterbeeck, was executed by fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. and son Peter Verbruggen, and consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words. by the Maecenas-bishop in 1670.

Gigantic marble pillars, with a diameter of about 63.5 cm (= 2 ft) and a weight of about 4,500 kg carry an immense broken fronton with two curling shells.

In the central niche Paul, the apostleThis is the name given to the principal twelve disciples of Jesus, who were sent by Him to preach the gospel. By extension, the term is also used for other preachers, such as the Apostle Paul and Father Damien (“The Apostle of the Lepers”)., is honoured with his title ‘doctor gentium’, the teacher of the gentiles. With a sword and a book in his hand he shows that he is prepared to die a martyrSomeone who refused to renounce his/her faith and was therefore killed. Many martyrs are also saints. for the preaching of the word of God: Jesus’ gospelOne of the four books of the Bible that focus on Jesus’s actions and sayings, his death and resurrection. The four evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. ‘Gospel’ is the Old English translation of the Greek evangeleon, which literally means ‘Good News’. This term refers to the core message of these books.. The two open books by his side may refer to the books of the Old TestamentPart of the Bible with texts from before the birth of Jesus., which he no longer regards as God’s final word, but only as a prelude to the New TestamentPart of the Bible with texts from after the birth of Jesus. This volume holds 4 gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, 14 letters of Paul, 7 apostolic letters and the Book of Revelation (or Apocalypse).. With an almost imploring gesture he looks at his audience sternly. Above the niche four small angels come flying in to offer him the attributes of divine reward for martyrdom: a laurel wreath and a palm.

The Dominican and former prior Marius Ambrosius Capello, bishop of Antwerp, wanted to bequeath to his convent an unforgettable present: the marble portico altar, up high in the sanctuary. The then prime cost of 80,000 guilders is the equivalent of no less than 3.8 million Euros today. The colossus, designed by Ambrosius’ private chaplain Frans Van Sterbeeck, was executed by father and son Peter Verbruggen, and consecrated by the Maecenas-bishop in 1670.

Gigantic marble pillars, with a diameter of about 63.5 cm (= 2 ft) and a weight of about 4,500 kg carry an immense broken fronton with two curling shells.

In the central niche Paul, the apostle, is honoured with his title ‘doctor gentium’, the teacher of the gentiles. With a sword and a book in his hand he shows that he is prepared to die a martyr for the preaching of the word of God: Jesus’ gospel. The two open books by his side may refer to the books of the Old Testament, which he no longer regards as God’s final word, but only as a prelude to the New Testament. With an almost imploring gesture he looks at his audience sternly. Above the niche four small angels come flying in to offer him the attributes of divine reward for martyrdom: a laurel wreath and a palm.

The white marble busts of the four Western Church Fathers enliven the black marble altar base, because they are symbolic of the theological brainwork that wants to connect faith with reason. From left to right: Jerome, the penitent, with the trumpet of the Last Judgment; Ambrose of Milan with the beehive of (honey-sweet) eloquence; in the centre pope Gregory with the allegoric dove of the Holy SpiritThe active power of God in people. It inspires people to make God present in the world. Jesus was ‘filled with the Holy Spirit’ and thus showed in his speech and actions what God is like. People who allow the Holy Spirit to work in them also speak and act like God and Jesus at those moments. See also ‘Pentecost’., which inspires at teaching; Augustine with the flaming heart. They share ‘the honour of the altars’ with Saint Thomas Aquinas, the famous Dominican theologian and ‘Doctor of the Church’ since 1567, on the extreme right.

The commissioner could not resist immortalizing himself in this monument, although in a relatively modest way. There are also a few biographical references of his, referring to his religious development: as a baptized Christian, as a religious with three vows, as an enthroned bishop.

Nearly invisible details on Gregory’s cope allude to Capello’s baptismal name, because two tableaus in ‘embroidery’ refer to Saint Marius, a Persian who came to Rome in the third or fourth century. Just like the honourable Quirinus he was concerned about the Christian prisoners. Marius looks into the prison through the barred window (scene on the left). Afterwards Marius sought contact with Christians, attracted by their singing of psalms. Out of fear for the police they open the door for him only hesitatingly (scene on the right). The same ‘embroidered medallion’ is to be seen on the cope the white marble bishop Capello is wearing on his tomb in Our Lady’s CathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is. (Artus II Quellinus, after 1676).

Because Capello received the name Ambrosius as a monastic name when entering the order, after the Dominican beatified Ambrosius Sansedonius, Ambrose of Milan was also his patron saint. This was a rewarding occasion to eternalize Capello’s portrait as the Church Father’s face.

Between the statue of Saint PaulOriginally, he was called Saul, he was a Jew with Roman citizenship and a persecutor of Christians in the period shortly after the death of Jesus. After his conversion, he became the main gospel spreader in what is now Turkey and Greece. He wrote letters to keep in touch with the Christian communities he had founded, and these texts are the oldest ones in the New Testament. Although he never met Jesus, he is called an “apostle”. and the altar painting bishop Capello’s coat of arms is prominently present.

Stimulated by the example of the Jesuits nearby (the present Charles Borromeo’s Church), the Dominicans also provided their Baroque portico altar with a system that allowed them to change altarpieces, albeit with only two paintings. These were put at both sides of a long vertical axle, with their backs against each other. Besides the Rubens mentioned The Martyrdom of St Paul by Theodoor Boeyermans (ca. 1670) could be admired. In 1794 both paintings were requisitioned by the French occupiers and transferred to Paris. In 1811 Napoleon gave them to regional museums. After the Battle of Waterloo this was a nice alibi for the French not to consider them as part of the collection of paintings the Louvre had to repatriate. This explains why Rubens’ Saint Dominic is now the eye-catcher of the Lyon Musée des Beaux Arts, and Boeyermans’ Saint Paul is in Aix-en-Provence, now in Ste Marie Madeleine Church.

In substitution for these masterpieces Cornelis Cels painted The descent from the cross, which is however quite academically cool, in 1807. Could the mechanism to change paintings be reinstalled to include a second painting, a more contemporary creation? But then this new painting will also have to measure 5.55m x 3.72m (= 18ft 2½in x 12ft 2½in)!

Around 1670, for the second painting, The martyrdom of Saint Paul, Theodoor Boeyermans was completely inspired by Rubens, who had treated this theme for the Rood Klooster near Brussels. Paul is partly kneeling on a hill, his eyes upward to Heaven, awaiting the fatal gash that will make his head roll. At Paul’s request Plautilla is coming to blindfold him, following the Legenda Aurea by Dominican De Voragine. The lookers-on on the hill flank, soldiers and Christians, help to constitute the diagonal (upward) axle leading to the spot of the execution. Angels already bring the laurel wreath and the palm of Paul’s Heavenly victory.

The white marble antependiumLiterally: “something hanging in front”. An ornament placed in front of the altar and usually covering it completely. An antependium can be made of various materials: silver (as in Antwerp cathedral), wood but also textiles. In the latter case it is sometimes adapted to the liturgical colours. (Jan Baptist de Cuyper, 1845) contains an extraordinary representation of EucharisticThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live. Christ: Jesus’ real presence in the Eucharist.

In the 17th century stained-glass artist Abraham Van Diepenbeeck got the commission to represent the story of patron saint Paul in the ten windows at either sides of the choir.

The four stained-glass windows we can now see behind the high altar (H. Leenen, 1967) are a reminder of saints that were popular in the former parish church, Saint Walpurgis: Saint Eloy, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Amandus and Saint Walpugis.

The scientific justification of the data concerning the sanctuary of the Antwerp Saint Paul’s church can be foundHERE.

It is basically written in Dutch, but using the translate button you can ask for an instant translation in English

- Saint Paul’s Church

- History and description

- Introduction

- Historic context

- The building history

- Saint Dominic

- Saint Paul

- The tower

- The architecture

- Floor plan and legend

- The sanctuary

- Chapel of the Holy Sacrament

- Our Lady’s chapel

- The mysteries of the Rosary

- Sermon, confession, music

- The mural paintings

- The treasury

- The Calvary garden

- Veemarkt gate

- Dominican pastoral activities

- Dominican convent

- The paintings in the cloisters

- Holy Cross Chapel

- SPK The weekly chapel

- Bibilography