Saint Paul’s, the Antwerp Dominican church, a revelation

The architecture: gothic and symbolism

In the duchy of Brabant, to which Antwerp belonged, the international Gothic style, developed into a specific regional variant, especially in church building. The characteristics of this Brabant Gothic style, applied to SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Paul’s, are:

- a very austere exterior architecture. ConventComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. churches are boxed in anyhow, but in 16th century Brabant also city churches were surrounded by houses, so that at the outside only the porches were visible. A sober design is also the characteristic of mendicant orders. In Saint Paul’s the late Gothic tracery in the mullioned windows is the only exterior decoration.

- compartmentalized corridors with (high) parapets underneath the upper windows, as a kind of corruption of the original triforium.

- pillars on octagonal bases. Sometimes, as in Saint Paul’s these pillars are cylindrical and are crowned with capitals with cabbage leaves motifs. The effect of this is less streamlined than that of compound pillars without capitals.

- the more elaborate compartmentalization of the stained glass windows has been limited to four here. Because only little wall surface remains, the result is exceptionally elegant, especially since the proportions are so balanced: the lower arcade takes as much space as the clerestory, and the balustrade of the corridor serves as a discrete separation.

For the interior walls brick was used, whereas the exterior paraments and constructive parts have been made of sandstone (“Ledische zandsteen”).

Dimensions

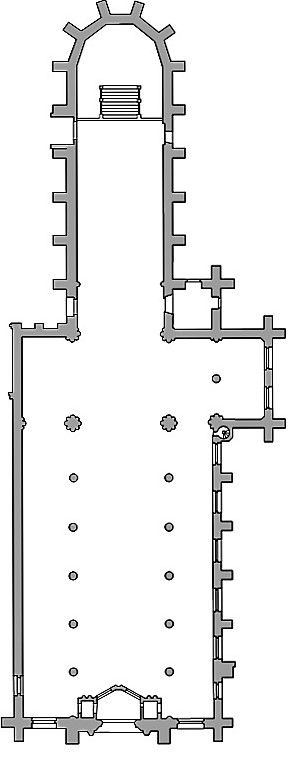

| length: | in total ca 88 m (589ft), consisting of the naveThe rear part of the church which is reserved for the congregation. The nave extends to the transept. (38.32 m = 125ft 8in), the transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right. (11.60m = 38ft) and the choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. (39m = 128ft) |

| height: | nave, transept and choir: 24.9m (81ft 6in), crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept].: 26m (85ft 3in) |

| width: | in total 25m (82ft), of which the central naveThe space between the two central series of pillars of the nave. 11.3m (37ft), the choir 11.1m (36ft 5in) |

| The total roof surface is about 3,000m² (32,292 ft²), it is covered with nearly 200,000 slates, of which each has been fastened with two copper nails and of which the total weight is 87 tonnes. |

With some spatial symbolism

Now the floor level of the church is about 1.7m (= 5.5ft) above street level. The steps in Nosestraat make one experience the figurative ‘elevation’ of the sacred space, reminding us of the psalm-verse “Let us go up to the House of the Lord” (Ps. 122:1) Here you are assimilated into Beauty, which exceeds temporality. After all the church is not a common space for religious services, but wants to evoke ‘Heavenly Jerusalem’. The consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words. church first of all is meant to be the house of God, where one may be a guest, especially at the altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine., and where one lets himself being filled with the Light of God’s presence. Here one enters into a different dimension of life, which refers to the Perfect and the Eternal. The sacred space makes it possible to experience God’s presence thanks to the following characteristics:

The grandeur

The height, which is 24.9m (81ft 6in) in the choir and 26m (85ft 3in) in the stellar vault, combined with the depth (of 88m = 289ft), which is so extraordinary thanks to the long choir, determines the grandeur. It is a pity that the coloured light of the stained glass windows, which marked the space even more, has disappeared. The special effect must have been even bigger for those who, in former days, lived in a small house such as the ones at the foot of the façade (p. 17). Symbolically this religious idea of God’s eternity (‘transcendence’) is supported by the golden stars, which represent the firmament of Heaven. In the same way as we cannot grasp the stars with our hands, we cannot grasp God with our brain. However much God transcends our limited intellectual capacity was depicted in a 15th century painting on a side altar. In it we see Saint Augustine on the beach, meeting a little boy who tries in vain to pour the water of the entire sea into a little pit. The saint, who questions the seriousness of this attempt, receives the reply that his attempt to understand the full mystery of God is even less realistic.

Orientation

The grandeur of the church building wants to make us experience God as the Lord of all life. The orientation of the church however indicates that God came closest to mankind in His Son Jesus. By his sacrifice of Love until his death on the cross, and by His resurrectionThis is the core of the Christian faith, namely that Jesus rose from the grave on the third day after his death on the cross and lives on. This is celebrated at Easter. this Jesus has overcome evil and has deprived death of the last word. That is why for Christians He is ‘the Saviour of the world’, ‘the Light of the world’ (after John 1:5). This explains why, just like every single medieval church, Saint-Paul’s has been oriented, i.e. with the high altar and the side altars oriented towards the East, where the sun rises. Just like sunlight engenders the new day and by its light and warmth makes everything grow and blossom, Jesus offers real light to people. Christians orient themselves to Him. In the church building they do so literally and symbolically: the believers, led by the Preachers, directed their prayers in the divine offices and in the (morning) EucharistThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live. towards the sun rising in the East.

The cruciform floor plan

That the immeasurable God shows Himself in Jesus Christ, can be seen in the floor plan, which has the form of Jesus’ cross. In other words: the floor plan of the church shows that this ‘house of God’ is indeed of Christian nature, which can be seen best in an aerial photo of the choir, nave and transepts.

The most important part is the choir, the ‘sanctuary’. Here the Preachers gathered a few times a day to pray the divine offices. This is why this choir has been conceived as the head of the crucified Jesus. After all the church community is the “mystical body of Christ” (Saint PaulOriginally, he was called Saul, he was a Jew with Roman citizenship and a persecutor of Christians in the period shortly after the death of Jesus. After his conversion, he became the main gospel spreader in what is now Turkey and Greece. He wrote letters to keep in touch with the Christian communities he had founded, and these texts are the oldest ones in the New Testament. Although he never met Jesus, he is called an “apostle”.) with the clergy as “its head”.

The transepts represent the transverse beam of the cross.

When Jesus died at the cross, His mother remained loyal to Him until the end; this is why Mary receives the place of honour in a crucifixion scene, i.e. Jesus right hand side. This is also the reason why in the cruciform floor plan of a medieval church as this one, Our Lady’s Chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

is on the right, which is the northern side.

With the Apostles as symbolic pillars

The symbolism of the twelve apostles is present in the very architecture of the church building, more specifically in the twelve pillars bearing the central nave. In his EpistleIn Mass, the Bible reading(s) preceding the gospel reading. According to the lectionary, there are always three readings on Sundays: one from the Old Testament, one from the non-gospel texts of the New Testament and one from a gospel. The first two readings are often called the epistle but strictly this word refers only to the letters of St Paul and other apostles. to the Galatians (2:9) Paul calls the apostles “the pillars” of the Church. In Revelations (21:14), where the wall of Heavenly Jerusalem is supported by twelve pillars with in between the names of ‘the Twelve’, the architectural symbolism is even more explicit.

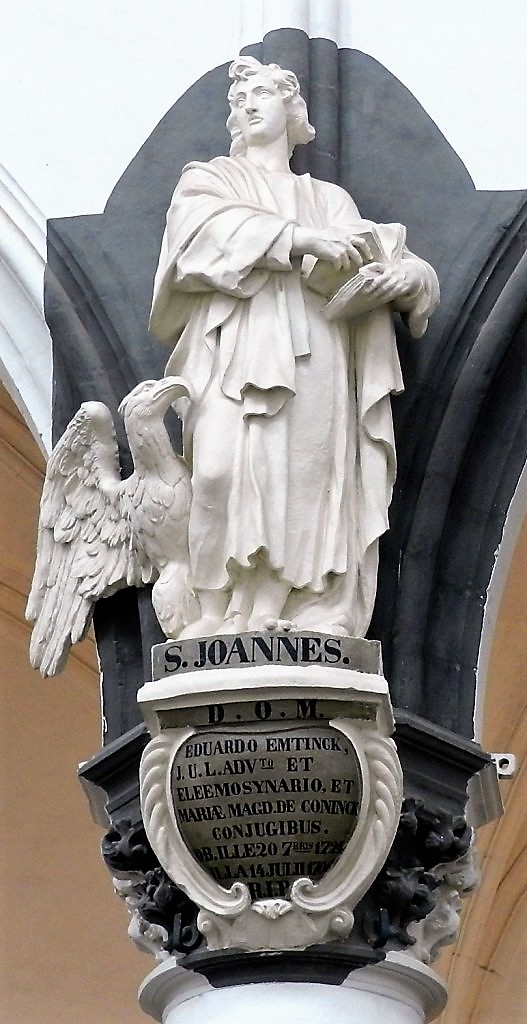

At the top of each pillar there is a more than life-size white stone apostleThis is the name given to the principal twelve disciples of Jesus, who were sent by Him to preach the gospel. By extension, the term is also used for other preachers, such as the Apostle Paul and Father Damien (“The Apostle of the Lepers”). statue (2.25m = 7ft 4in tall), sculpted by Michiel I van der Voort. Preliminary studies of these are kept in the Antwerp Print Room; one bozzetto, that of Andrew, is in Brussels (KMSKB).

So as to be able to realise the series of statues financially, each apostle statue became part of a funeral monument of a single wealthy citizen, with the huge plinth carrying the text of their epitaph. All persons who continue ‘living’ here in memory belonged to the same Emtinck family of substance. The order of the names of the family members is chronological according to the date of their death. The series starts with Peter, and Eduard I († 1620), the Antwerp primogenitor. Eduard III († 1724), lawyer and almoner, as mentioned in his epitaph below the apostle John, seems to have been the most central character of the twelve family members mentioned. He is the fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. of the six children whose names were written underneath the last six apostle statues – sometimes even decades – after the series had been realised. Moreover his date of death matches best the stylistic dating between 1700 and 1720.

The position of the apostle statues, from East to West

| Central nave North | Central nave South |

| 1. Peter | 2. Paul |

| 3. Andrew | 4. James the Greater |

| 5. John | 6. Thomas |

| 7. James the Less | 8. Philip |

| 9. Bartholomew | 10. Mathew |

| 11. Simon the Zealot | 12. Jude Thaddaeus |

True to tradition the apostles are barefoot – reminding Jesus’ advice when He gave them their mission to proclaim faith. In order to create a more vivid impression, most figures have one foot protruding from above the plinth. The contrast with the wide folds in their garments accentuates the muscled anatomy of these half naked Men of God. All of them have beards, except for John and Bartholomew. Many carry their instruments of torture as attributes.

It is quite original that all apostles who contributed in writing to the New TestamentPart of the Bible with texts from after the birth of Jesus. This volume holds 4 gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, 14 letters of Paul, 7 apostolic letters and the Book of Revelation (or Apocalypse)., however small their contribution may have been, are represented as authors, with their writings being depicted in proportion to the volume of their contribution. Could this underline the intellectual procedure of the Dominicans when preaching?

- Peter, the first in the order of merit, deserves being in the first place of honour, which is on the right in the cruciform floor plan. He does not carry the instrument of his torture, but only both keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, which he metaphorically received from Jesus. Does his gaze towards the choir suggest that he transfers this symbol of churchly power to the priests?

- As he is one of the most important authors of the New Testament, Paul keeps a scroll of at least eight pages in his left hand beside him, while as a great preacherA priest, deacon or lay person who explains the Bible readings during the celebration of Mass. Sometimes a preacher also acts outside of Mass celebrations (and in the past he did so regularly) to clarify certain points of faith and to encourage the churchgoers to a more Christian way of life. he extends his hand in a rhetoric gesture in the direction of the Dominicans in the choir.

- With one hand Andrew clutches the instrument of his torture, the Saint Andrew’s cross behind him. The wide gesture of his lifted open left hand, followed by his upward gaze, expresses his preference for Heaven. Although this statue is far less heroic the composition is indebted to Frans du Quesnoy’s masterpiece in Saint Peter’s in Rome.

- James the Greater is walking as a pilgrim, with a cloak, a staff and a travelling bag. As a true guide he indicates the direction with this right hand.

- John, the latter’s brotherA male religious who is not a priest., and also an evangelist, exceptionally looks right in front of him and not to Heaven. He leafs through a book that is open at two excerpts. This might be an allusion to the various texts that in those days were still attributed to him. The monumental eagle at his side, with the mighty, true to nature, spread right wing is looking up at ‘his master’.

- Thomas, who is also nicknamed ‘doubting Thomas’, plucks his beard uncertainly. The spear, the instrument of his torture, consists of a wooden stick with a metal point nailed on to it.

- James the Less uses the instrument of his torture, a big club, as a stick to lean on. With his index he points at a quotation in the scroll of three pages, alluding to his Epistle.

- Philip clutches a big Latin crossA cross of which the lower part of the vertical beam is significantly longer than the upper part. with his both hands.

- Bartholomew is holding [only the hilt of what is left of] the knife, the instrument of his torture. He is identified with Nathanael, who is always mentioned together with Philip.

- Matthew, the evangelist, is holding a bulky book, while his right foot is on a small pile of books: the registers of his former tax office, which he does not use anymore.

- Both hands of Simon the Zealot clasp the large saw, with which he is said to have been sawed through in Persia. His right elbow rests on a shortened trunk: a welcome support for the artificial crossing of his legs.

- As a martyr Jude Thaddaeus is holding three cobble stones in his lap. As he is the writer of one and also the shortest epistle of the New Testament, he is holding one tiny scroll in his right hand.