The Antwerp jesuit church, a revelation.

Our Lady's chapel

An unusual spectacle

Even more spectacle is to be found in the extraordinarily rich Our Lady’s Chapel

Even more spectacle is to be found in the extraordinarily rich Our Lady’s Chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

. This was realised thanks to the maecenatism of the three Houtappel sisters from Ranst, who were ‘spiritual daughters’ living according to the Jesuit spirituality.

This fantastic chapel is the best place in Antwerp to be carried away by whimsical Baroque art. Here Baroque is at its best with the natural fanciful lines in marble panels, nicely painted marble panes, true to nature flowers, marble corncobs and grapes, a stucco ceiling with symbolic titles of honour for Our Lady, the mask-like plinths and relief, some of which are stylized. Who would not depart from here with a happy heart? Fortunately, this jewel was spared by the 1718 fire.

- Saint Charles Borromeo’s Church

- History & Description

- Introduction

- The historic context

- Square and residence

- Previous history

- The college

- Spatial effects

- Names of streets

- Profess house

- Sodality building

- Façade

- Tower

- Interior

- High altar

- Pulpit

- Confessionals

- Ceiling paintings

- Our Lady’s chapel

- Saint Ignatius chapel

- Chapel of Saint Francis Xavier

- Galleries

- Organ

- Sacristy

- When leaving

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

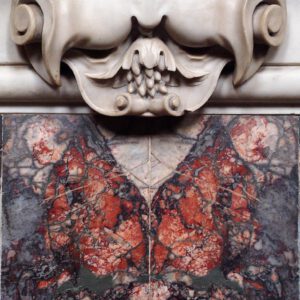

More Baroque is impossible

The variety of costly sorts of marble is exceedingly rich, also because some were recycled from antique Roman buildings. Notice for example two panels at the back of the chapel: so colourful that they can compete with a non-figurative painting. Mark the technique to obtain a symmetric composition. A block of veined marble is cut into two pieces in a way that the grains on the dividing line of both halves have been cut in two. When both halves are positioned precisely one next to the other, you get an almost perfect mirror view. When you were a child, did you ever cut a folded sheet of paper and then open it?

And then there is the Baroque repertory of decorative elements.

Masks: on the white marble pilasters of the triumphal arch and on nearly all capitals of the confessionals. Further there is a big one underneath the fronton of the confessionalA piece of furniture that was especially designed to facilitate the sacrament of confession, especially by avoiding that confessor and penitent come face to face. To the left and right are kneeling pews for penitents; in the middle is a small booth where the confessor sits. Both are separated from each other by a partition with a grid, so that the confessor can hear the penitent, but cannot see him / her. against the back wall, and a male mask distorted with pain, below the arch of the entrance.

Stylized faces: on the cartouche above both side doors and on the Northern wall there are four (!) of them on each of the plinths of the four big marble statues of saints against the side walls.

Garlands (with flowers) and festoons (with fruits, blossoms and foliage): beneath the triumphal arch, in the spandrels of the ceiling, on the side walls near the balconies, just below the three windows, on the portico of the altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine., on the confessionals: both above the priest’s cubicle and on the capitals.

Cornucopias: above the triumphal arch (just underneath the ceiling), stylized ones above the entrance, in the frames of two paintings on the south wall, in the cartouches of Jesus and Mary on the west wall.

Stylized sunflowers: on the pilasters of the triumphal arch.

Shells: as a nimbus above the four statues of female saints; next to the triumphal arch (double ones), above the two blank frames at the north wall, above each confessional.

Cartouches: above the triumphal arch (just underneath the ceiling) and at the confessionals.

The predellaThe base of an altarpiece. Like the altarpiece, the predella may be painted or sculpted.

Life of mother and child

The elegant statue of Our Lady, which was carved out of wood from the miraculous Scherpenheuvel tree, was a present from Archduke Albert and archduchess Isabella.

The elegant statue of Our Lady, which was carved out of wood from the miraculous Scherpenheuvel tree, was a present from Archduke Albert and archduchess Isabella.

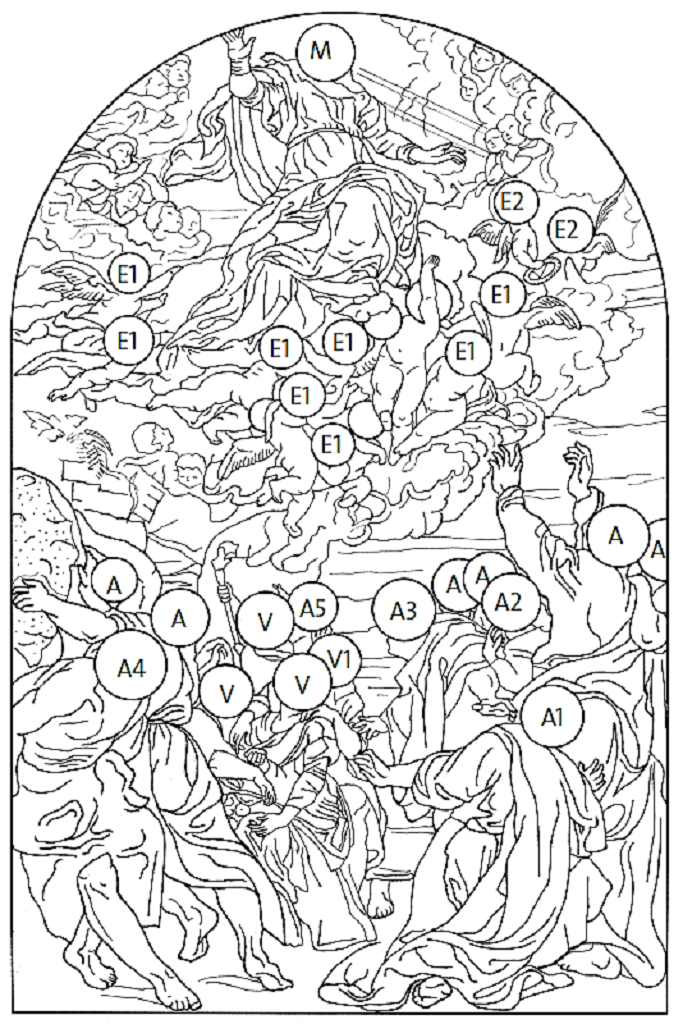

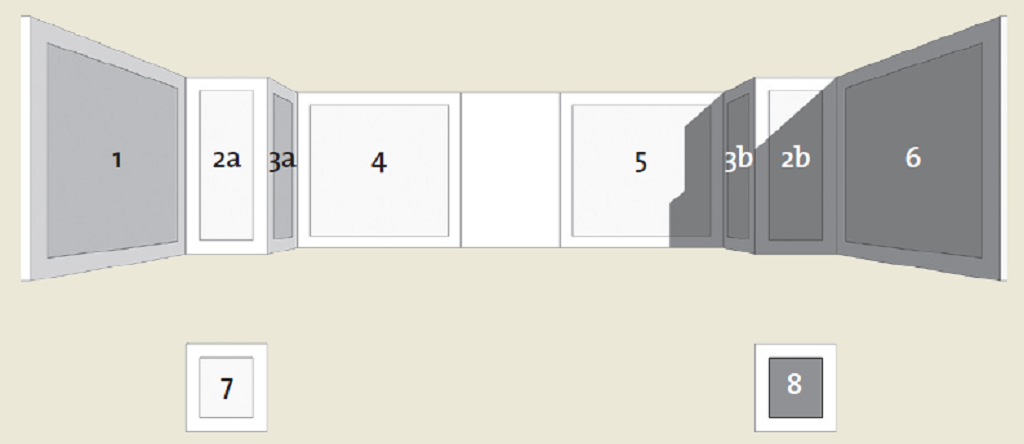

The life of Mary can be followed in 8 peculiar scenes, painted by Hendrik I Van Balen (1560-1632) on marble panels in the walls of the little apseSemi-circular or polygonal extension where the high altar is located in a church.: at the sides in front, as the predella of the altar, and also in the niches destined for the liturgical implements. The colour of the marble panels has been chosen in accordance with the themes of the scenes. This explains why for the walls and floors of a plain house brown ochre marble was left unpainted (2a-2b, 3b), whereas to represent the more important Temple architecture white marble was left unpainted (1,6,7,8). But using (unpainted) marble as a support medium is at its best when the veins of the brown ochre marble are used playfully to represent fanciful rock masses (3a,4,5).

Let us have a look at Mary’s photo album

- The presentation of Mary at the Temple; a purely apocryphal element, introduced as a kind of parallel with Jesus’ Presentation at the Temple.

- The annunciation: the private scene with Mary (a) on the left plinth of the altar painting, the angel (b) on the right one.

- On her way to Elisabeth

- a rare representation (a) (the child Jesus is not yet with her; not to be confused with the Flight into Egypt, where Jesus is present).

- Arrival (b): the actual visit of Mary to Elisabeth.

- Jesus’ birth, or the adoration of the shepherds.

- Jesus’ revelation, or the adoration of the magi.

- The presentation of Jesus at the Temple, which is also called the Purification of Mary because she follows the Jewish purification rites for cleansing after (having lost blood at) childbirth.

- Jesus is being sought in the Temple, in the niche for liturgical implements on the left.

- Jesus is being found in the Temple, in the niche for liturgical implements on the right.

The altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella.: Our Lady’s assumption (Peter Paul Rubens)

Between two helical Tuscan columns the high point of Mary’s life, her assumption, painted by master Rubens, is displayed hugely above the altar.

The commission to Rubens

Around 1611 the church councilA large meeting of ecclesiastical office holders, mainly bishops, presided by the pope, to make decisions concerning faith, church customs, etc. A council is usually named after the place where it was held. Examples: the Council of Trent [1645-1653] and the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965], which is also the last council for the time being. of Our Lady’s CathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is. decided to commission a new altarpiece for the high altar. The chapterAll the canons attached to a cathedral or other important church, which is then called a collegiate church. In religious orders, this is also the meeting of the religious, in a chapter house, with participants having ‘a voice in the chapter’. preferred not ‘Mary’s crowning’, for which both Otto van Veen and Rubens had submitted a design, but a second design by Rubens, representing Mary’s assumption. The lower part of this painting however is a mirror view of Rubens’ design for Mary’s crowning that is kept at the Hermitage in SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Petersburg. This version, which was finished in 1613, never got into the Cathedral, but ended up in this Our Lady’s chapel, which was only built after 1620.

Further history

In 1776 empress Mary Theresa bought this panel. It is now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. In 1925 parishioners of Saint Charles had the original painting copied, so that now we can again have an impression of the original entity.

Iconography

The moment represented is called The Assumption of MaryThis feast – on August 15 – plays an important role in the veneration of Mary as the Mother of God. As the most important saint, it is obvious to Christians that upon her death she was immediately received into the heavenly paradise. In the Eastern Churches, this is called the feast of “the Falling Asleep of the Mother of God”, i.e. her death, which immediately means a heavenly rebirth. In Antwerp they also celebrate Mother’s Day on that day. Some people also call this the Ascension of Mary, which is wrong. Unlike Jesus, who as God Himself could return to the place where He is at home, Mary could only be taken up to heaven through God the Father and Jesus., in accordance with the official name of the liturgical feast on 15th August. That the Virgin Mary ‘was assumed body and soul into Heavenly glory’ means that Heavenly glory is a gift from God, which we cannot provide for ourselves. Already in Rubens’ time the notion ‘Mary’s Ascension’ was used, due to the similarity with the Feast of the Ascension. Theologically it is less correct to talk about Mary’s ascension, because in this way it is suggested that the transition into eternity would be the result of man’s own power.

The full attention that is given to Mary here, is characteristic of the Counter Reformation, which tries to defend Mary’s honour against the Protestants. But also without this context of controversy and discussion it can be understood why Mary is put in the spotlight: she is the outstanding example of every man who is on his way in this life, looking forward to his homecoming in the heavenly Father’s house.

The story must be read from left to right, and then diagonally upward. By analogy with Jesus’ tomb, Mary’s is represented here as a Jewish cave tomb. On the foreground left some apostles (A) roll the stone away from it. The one who is most to the front and closest to the frame of the painting (A4), directs his look to the spectator outside the painting. His gaze means as much as: “Do you too want to penetrate into this mystery of mankind? Then watch closely.” Another disciple (A5) lights the cave tomb with a torch. Between these two, 4 women (V) inspect the shroud and establish the miracle of roses: a classic legend by the medieval Dominican Jacopo de Voragine O.P., which was still popular in the Baroque period. Mary Magdalene (V1), with the long blond hair, points at the roses. Just like the woman in front of her she makes eye contact with the first group of apostles (A3) on the right, who are astonished and follow Mary’s (M) mysterious transition to Heavenly bliss admiringly. Each of them reacts with different gesticulations. Peter (A1) can be recognized by his physiognomy and sits on his haunches fully on the foreground. The young man in the centre, dressed in green and not in his classic red, is John (A2). Together with the four men on the left we can count 11 apostles – which matches the gospelOne of the four books of the Bible that focus on Jesus’s actions and sayings, his death and resurrection. The four evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. ‘Gospel’ is the Old English translation of the Greek evangeleon, which literally means ‘Good News’. This term refers to the core message of these books. before the election of Matthias as the 12th apostleThis is the name given to the principal twelve disciples of Jesus, who were sent by Him to preach the gospel. By extension, the term is also used for other preachers, such as the Apostle Paul and Father Damien (“The Apostle of the Lepers”)..

Mary (M) is triumphantly flocked by a nearly closed circle of angels (E). The jubilant angels (E1) underneath her help her push into Heaven, whereas other angels (E2) beside her in the clouds already welcome Mary in Heaven. Mary is wearing a white tunic and a fluttering white cape. That Mary has reached Heaven closely is suggested by the composition: she is in the centre on the highest level of the composition, her head just underneath the semi-circular frame. From above some probing, heavenly golden light falls like a fan onto her head. Not only is her gaze directed to God, with her right arm directed upwards she touches the painting’s frame and reaches her hand cravingly to God.

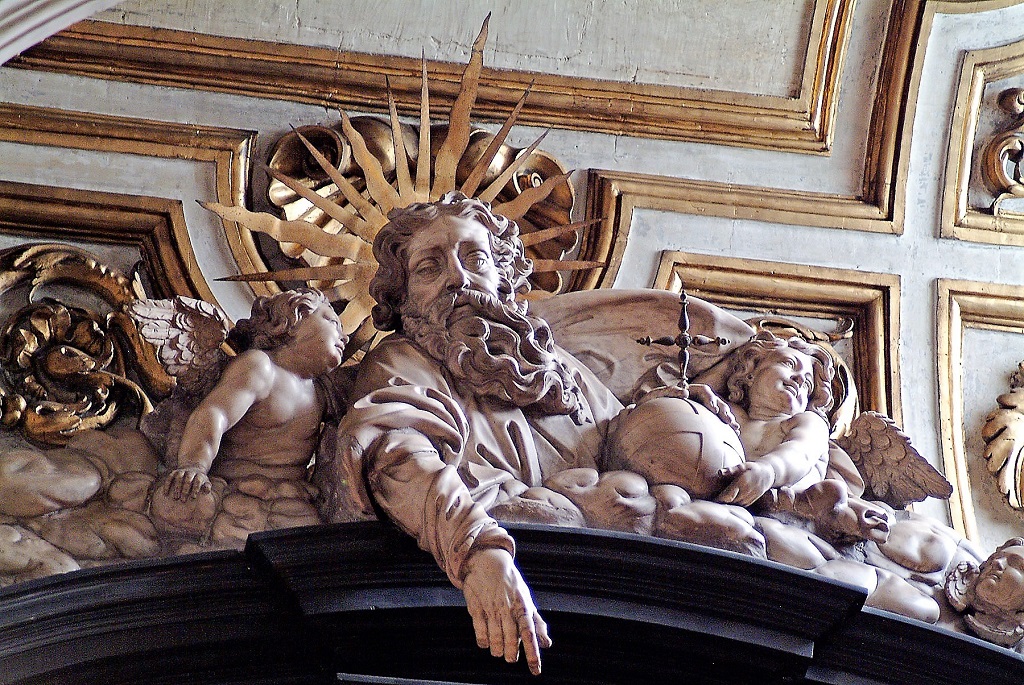

The goal of this assumption, God in Heaven (G), is not situated in the flat colourful painting, but above it, in the semi-circular crowning, in the more spatial, three-dimensional, fully plastic white marble sculpture. Indeed, being adopted by God is a totally different dimension. The fact that God is somewhat hidden from the spectator’s view and the indirect incidence of light create a theatrical effect that reinforces the transcendent character of the event.

Initially Mary was offered a heavenly reward, a golden crown, by God the FatherPriest who is a member of a religious order., held in His strong, marble hand. The crown symbolizes the reward of eternal life for the one who is faithful until death, according to Revelations 2:10. And on the black marble key stone of the semi-circular frame there was the text: “VENI CORONABERIS” (Come, you will be crowned). Thus, the painting by Rubens and the marble sculpture from Colijns de Nole’s workshop form a thematic unity. It happens to be one of the main characteristics of Baroque to gear different artistic genres to one another so that they culminate in one impressive effect.

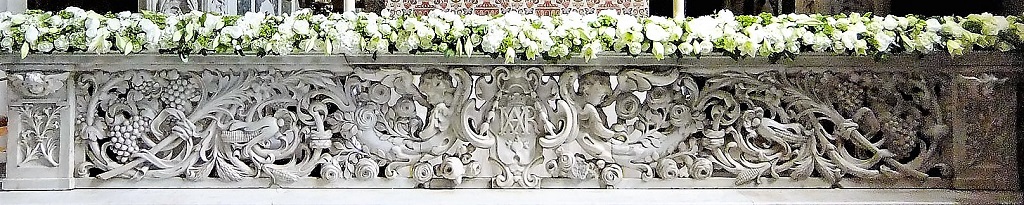

The communionThe consumption of consecrated bread and wine. Usually this is limited to eating the consecrated host. rails

The marble communion rails, of which however the door is missing, replaced the original wooden one. In 1657 the donor, Anna Houtappel, the last of the family to survive, paid the sum of 1,800 florins for this piece of EucharisticThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live. furniture. Its floral symbols – the rose of election and the lily of purity – are entwined with other plant symbols for (Jesus’ presence in) the Eucharist: ears of maize (instead of the smaller ears of wheat) for the bread of the HostA portion of bread made of unleavened wheat flour that, according to Roman Catholic belief, becomes the body of Christ during the Eucharist., and grapes for the wine.

The marble communion rails, of which however the door is missing, replaced the original wooden one. In 1657 the donor, Anna Houtappel, the last of the family to survive, paid the sum of 1,800 florins for this piece of EucharisticThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live. furniture. Its floral symbols – the rose of election and the lily of purity – are entwined with other plant symbols for (Jesus’ presence in) the Eucharist: ears of maize (instead of the smaller ears of wheat) for the bread of the HostA portion of bread made of unleavened wheat flour that, according to Roman Catholic belief, becomes the body of Christ during the Eucharist., and grapes for the wine.

The paintings on the walls

Five more paintings, fitted in heavily decorated marble frames, show that Mary is worth all possible attention.

- Against the southern wall, on the left, there is The adoration of the child Jesus by angels, painted by Gaspar van Opstal (1693), replacing a canvas by Gerard Seghers (1591-1651), After his resurrectionThis is the core of the Christian faith, namely that Jesus rose from the grave on the third day after his death on the cross and lives on. This is celebrated at Easter. Christ appears to His mother, which is now owned by KMSKA and is kept in the Plantin-Moretus Museum.

- Right of it there used to be another apocryphal theme: Our Lady receives Holy Communion from Saint John the Evangelist, also by Gerard Seghers. After the church had been re-opened under Napoleon, it was replaced by The Annunciation (C. Van der Borght, 1811).

- Facing the altar there is Christ’s circumcision (Cornelis Schut, 1st half 17th century). Mary, who is holding Jesus on her knees, is looking at the dish in front of her, on which her child’s foreskin will be laid. Saint Joseph performs the ritual himself. The blood and pain of the circumcision (Lc. 21:21) function as a prefiguration of the Christ’s passion. This is why the naked child Jesus reaches out his little arms to the cross that is held to him by an angel, while putti and angels bring the other tools of passion: whip, crown of thorns, lance, baluster (whipping post). In his Spiritual Exercises (nb. 266, point 3) one also meditates the grief of mother Mary: “They gave the Child back to his mother, who pitied him because of the blood that ran from her Son”.

- For the Jesuit order the liturgical feast of the Circumcision (1st January) was an important feast, because then Jesus officially received His name, after which the order – the Company of Jesus – has been named. Moreover, the identification of Jesus’ Name with His Blood and crucifixion was an important theme in Jesuit preaching. The Jesuit who wants to follow Jesus, must be prepared to give everything for His Name, even his life after (bloody) torture.

- Mary’s Assumption (once again), by Cornelis Schut.

- Next to the entrance The Holy Family, attributed to Jan Lievens (1607-1671), who was married to Susanna, Andries Colyns de Nole’s daughter. The banderol of the small John the Baptist already contains the words he will identify Christ with later: “ECCE AGNUS DEI” (Behold the Lamb of God; John 1:29). A lamb is down the stairs and is looking up at the One it is symbolizing.

Ceiling reliefs with Mary’s titles of honour

The ceiling of the chapel wants to carry Mary’s glorification to an extreme. The main motif is Mary’s name, surrounded by about ten of her symbols occurring in the Litany of the BlessedUsed of a person who has been beatified. Beatification precedes canonisation and means likewise that the Church recognises that this deceased person has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. Like a saint, he/she may be venerated (not worshipped). Some beatified people are never canonised, usually because they have only a local significance. Virgin Mary, the so-called Litany of Loreto. It is a fact that P.P. Rubens designed the stucco. A drawing by his hand is kept in the Albertina in Vienna. We are not sure who executed it. Sometimes the sculptor Andries Colyns de Nole is mentioned.

The ceiling of the chapel wants to carry Mary’s glorification to an extreme. The main motif is Mary’s name, surrounded by about ten of her symbols occurring in the Litany of the BlessedUsed of a person who has been beatified. Beatification precedes canonisation and means likewise that the Church recognises that this deceased person has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. Like a saint, he/she may be venerated (not worshipped). Some beatified people are never canonised, usually because they have only a local significance. Virgin Mary, the so-called Litany of Loreto. It is a fact that P.P. Rubens designed the stucco. A drawing by his hand is kept in the Albertina in Vienna. We are not sure who executed it. Sometimes the sculptor Andries Colyns de Nole is mentioned.

In the centre of the square there is Mary’s monogram in heaven, near a few celestial bodies with Marian symbolism and joyfully surrounded by little angels.

- The sparkling sun: ‘as resplendent as the sun’ (Song of songs 6:10)

- a crescent moon: ‘as beautiful as the moon’ (ibidem)

- at the eastern side, a seven-pointed star: ‘a star shining among clouds’ (Sirach 50:6) or ‘Star of the Sea’, following the popular medieval hymn Ave Maris Stella.

- It is not a co-incidence that exactly above the communion rails there is the Ark of the Covenant. This chest containing the two tables in which the Ten Commandments or the Decalogue were engraved, is the sign of the first or ‘old’ covenant between God and His (Jewish) people (ex. 26:30). Here the Arch is symbol of Mary as the bearer of the New Covenant in Jesus, the Son of God or ‘the Word Incarnate’. The chest is between two angels facing each other and somewhat covering the Arch with their wings that extend towards each other. The Arch and the angels are together on one plinth. In both spandrels, an angel floats or sits with in both hands a crown of foliage and a palm, signs of Heavenly glory.

- The counterpart of this at the western side was also borrowed from the litany of Loreto. It is a Jewish altar of incense, gilded and with poles to carry it (Ex. 30:1). It is also flanked by two angels facing each other. Smoke is rising between them. With their wings outstretched over it they seem to be protecting the fire and fanning it. The altar and angels are on a cart here. In both spandrels, an angel is floating proclaiming Mary’s glory with a crumhorn.

On each of the two spandrels between the lunettes at both sides of the barrel vaulting there is a playful angel with a Marian symbol in his hand:

- To the north:

- a flower, possibly a lily

- a wreath of roses (a.o. the Song of Songs 2:1)

- To the south:

- a large vase, alluding to the titles ‘Spiritual vessel’ or ‘Vessel of honour’ and ‘Singular vessel of devotion’.

- a stainless mirror, symbol of her immaculate conception (not to be confused with her virginity!). (Wisdom 7:26)

The statues of saints

Four of the six life size white marble statues from Colijns de Nole’s workshop represent patron saints of the commissioners: the three Houtappel sisters and their cousin Anna ‘s Grevens. One single author even claims that they show the features of these ‘spiritual daughters’.

The donor of this chapel was Godefridus Houtappel, lord of Ranst and Zevenbergen. His tombstone is in front of the altar, beneath which there is the family cryptOriginally an underground burial chapel in which the relics of the saint to whom the church is dedicated were kept and venerated. The crypt is usually found under the choir. In a pilgrimage church it mostly has two staircases leading to it. This made it easy to organise the influx of pilgrims: they went down one flight of stairs and up the other.. The coats of arms of the Houtappel and ‘s Grevens families have been incorporated into the mural decoration. The ‘s Grevens coat of arms is above the triumphal arch, just underneath the ceiling. Anna was unmarried, which heraldically shows in the rhombic shape of her arms. The larger escutcheon of the Houtappel family has a more conspicuous position: in the middle of the back wall, where it catches the eye of anyone who enters the chapel.

- As a proud grandma Saint Anne shows a portrait of her daughter Mary and her grandson Jesus; an original and most exceptional representation of ‘Madonna and Child with Saint Anne’.

- The young Saint Christina in a luxurious dress, is holding an arrow in her right hand and has a snake around her left arm. This girl of distinguished descent from Bolsena (before the 6th century) was killed with arrows after several tortures including one with poisonous snakes.

- The elegantly dressed young royal princess, Saint Catherine of Alexandria († ca. 307/315), refused to comply with her father’s demand to renounce Christian faith. In his anger, her father wanted to kill her with a toothed wheel, but it broke. This fixed attribute is next to her while she is holding the palm of martyrdom in her hand. (left picture)

- Saint Suzanna, in a costly costume, also carries the palm of martyrdom in her right hand. This young Roman woman of noble birth (6th century) died a martyr’s death at home, because, due to her vow to remain a virgin, she refused to marry Emperor Diocletian’s son. She tramples the torch they wanted to light the faggot with, to make her die at the stake. (right picture)