The Antwerp jesuit church, a revelation.

The high altar

More than a table

What strikes one first when entering a Baroque church is its colossal high altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine.. In the Baroque, the altar slab is only a small part of an immense colossus. The mini comic strip of the Gothic triptych retable has evolved into a portico altar with one gigantic screen to be seen by all the persons present, also those – so to say – in the back seats (in the 17th and 18th centuries there were no chairs nor benches in the naveThe rear part of the church which is reserved for the congregation. The nave extends to the transept.). The gigantic altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. here is 5.35 m (17½ ft.) high (to be compared with two storeys of a house) and 4 m (13 ft.) wide. Didactics start with good teaching materials.

The high altar should remain an eye-catcher. To realise this, it has been made possible to replace the painting. Already then, the Jesuits realised that you hardly pay attention to an image when you always must look at the same one. Now we are used to changing quickly, even where the most beautiful picture of your life is concerned. Hence the reversible transparent cube with photos at six sides; or think of advertising boards along football pitches: how quickly they are changed! To obtain this variety the Antwerp Jesuits invented a unique system as early as the beginning of the 17th century. Behind the altar a large back up case has been constructed, in which four deep grooves offer place for as many paintings on canvas. There is a permanent system with a pulley that allows the canvases to be staged as their themes correspond with the Proper of the liturgical year. In this way massThe liturgical celebration in which the Eucharist is central. It consists of two main parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The main parts of the Liturgy of the Word are the prayers for mercy, the Bible readings, and the homily. The Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the offertory, whereby bread and wine are placed on the altar. This is followed by the Eucharistic Prayer, during which the praise of God is sung, and the consecration takes place. Fixed elements are also the praying of the Our Father and a wish for peace, and so one can symbolically sit down at the table with Jesus during Communion. Mass ends with a mission (the Latin missa, from which ‘Mass’ has been derived): the instruction to go out into the world in the same spirit. is thematically supported!

How can we explain this special attention Jesuits pay to the usage of images? In the method of meditation that Ignatius describes in his Spiritual Exercises, the sensory empathy into a Biblical passage is the starting point of further reflection. Especially through a visual representation you can feel more closely associated with the situation Christ or the saintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. is going through. In the Ignatian contemplation an image leads to emotions, emotions lead to thinking, in which the ‘discernment of spirits’ is of crucial importance. Hopefully this will lead you to making the right choices in your life. And it is by making the right choices that you contribute to “the greater glory of God” and that so you will come closer to Him.

Therefore, looking, beholding, has a key position in understanding a Baroque church, certainly for Jesuits. The representations are not meant to be a mere scenery to look at. You are supposed to empathize, to question. To sustain the meditation for the wider, illiterate audience qualitatively the masters of brush and chisel were invited and paid. The purpose of their artistic imaginative power in painting and sculpture is to cause emotions among the spectators. These emotions should evoke contemplation, good choices and in this way lead to God.

Two of the four original paintings – Saint-Ignatius and Saint Francis Xavier – were made by Rubens (ca. 1617-1618). They cost 3,000 florins for the two of them. Rubens’ masterpieces, The Descent from the Cross, for former Saint Walburga’s Church and The Raising of the Cross for the arquebusiers in Our Lady’s CathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is., were conceived for old-fashioned triptych altars seven years before. But these painting were adapted to the modern type of the rectangular portico altar. Both saints are represented as miracle workers: a popular representation in Counterreformation times, when a miracle was the utmost sign of holiness. “ (…) drive out demons, (…) speak new languages (…)drink any deadly thing and not be harmed (…) lay hands on the sick, and they will recover” are moreover signs Jesus promised to his apostles (Mc 16;17). And since Ignatius took the mission of the apostles as an example for his ‘Society of Jesus’, Jesuits tend to typify their big figures with such apostolic signs.

At the abolition of the Jesuit order nearly all paintings the Jesuits possessed were auctioned. But Joseph II, co-regent of the empress, wanted to acquire a few for the imperial galleries in Vienna, now the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Joseph de Rosa, who was the superintendent of the gallery, came here to make his choice before the auction catalogue was compiled. Some thirty pieces, especially masterpieces by Rubens, Van Dyck, Brueghel and de Craeyer, were transported to Vienna. Among them were the two Rubens’ paintings of the high altar and their respective oil sketches. There they would “at all times testify of the fame of the Flemish school of painting”. Together with two Van Dyck paintings that Mary Theresa had already demanded they yielded 60,620 guilders; the entire proceeds amounted to 98,100 guilders. The sale of all the other paintings from the Jesuit residences in Antwerp and Lier on 20th May 1777 in the college in Prinsstraat only realized 5,505 guilders. This low revenue for 853 paintings, 152 drawings and 8 sculptures can be explained by the fact that some ‘parties’ consciously depreciated the paintings out of sympathy for the Jesuits. The works for which too low a price was bid had to be withdrawn from the sale.

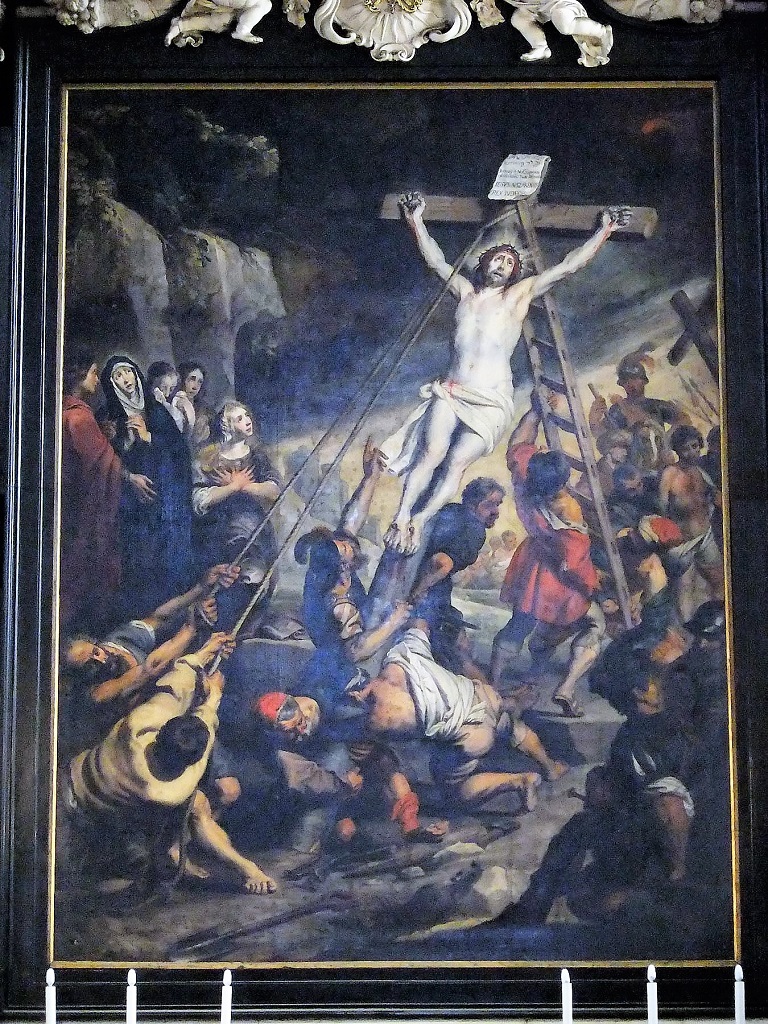

The two other paintings of the high altar can still be admired in turns:

- The crowning of Our Lady (Cornelis Schut), which remained on the spot

- The Raising of the Cross (Gerard Zegers), which could be bought back in 1839. This painting is exposed in LentThis is the period of preparation for Easter. It begins on Ash Wednesday and ends on the Saturday before Easter. Without the six Sundays of Lent, there are 40 days in which Christians are expected to live more austerely. The last week of Lent is called Holy Week. and calls up a prayer by Ignatius:

Dialogue with Christ

“Lord Jesus Christ, I see you right in front of me nailed to the cross.

What made you switch from Creator to man,

… switch from eternal life to untimely death

… die like this for my sins?

I look at myself and I wonder: What have I done for you?

What am I doing for you?

What ought I do for you?”

- In the present rotation of altar pieces Our Lady of the Carmel also takes part. This painting by Gustave Wappers came here in 1840, together with the statue of the same name, from the former Carmelite conventComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. in Meir. The statue is now at the entrance of Our Lady’s chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

. Some of Mary’s symbolic titles surround her: morning star, mirror, Ark of the Covenant, golden home, ivory tower. - And who has a good proposal for a new 4th (contemporary) painting?

The four life size statues of Jesuit saints in white Carrara marble (1657) in the niches of the choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. mediate between the meeting with God at the high altar and the believers in the church. Below there is Ignatius (North) and Francis Xavier (South), carved by Artus I Quellinus. On top Francis Borgia (North) and Aloysius Gonzaga (South) were probably sculpted by Hubert Van den Eynde. Ignatius, whose physiognomy was determined by his death mask, shows the book of constitution of his order. The great missionary Francis Xavier raises the mission cross and wears a stoleA long strip of cloth worn around the neck by the priest, the two ends of which are of equal length at the front. The stole is worn during mass and the administration of the other sacraments. to administer baptismThrough this sacrament, a person becomes a member of the Church community of faith. The core of the event is a ritual washing, which is usually limited to sprinkling the head with water. Traditionally baptism is administered by a priest, but nowadays it is often also done by a deacon.. Aloysius Gonzaga, who died young, is typified by a devotional crucifix, and Aloysius Gonzaga by a skull at his feet, to show his renunciation of worldly life. The loose folds of Borgia’s and Aloysius’ garments and the agility of Xavier’s rochetA long-sleeved, half-length white robe worn over a cassock. Rochet is a synonym. with long sleeves, are superb examples of a true-to-life rendering in marble.

- Saint Charles Borromeo’s Church

- History & Description

- Introduction

- The historic context

- Square and residence

- Previous history

- The college

- Spatial effects

- Names of streets

- Profess house

- Sodality building

- Façade

- Tower

- Interior

- High altar

- Pulpit

- Confessionals

- Ceiling paintings

- Our Lady’s chapel

- Saint Ignatius chapel

- Chapel of Saint Francis Xavier

- Galleries

- Organ

- Sacristy

- When leaving

- Epilogue

- Bibliography