The Antwerp jesuit church, a revelation.

The façade

Attention! Attention! A message for public advancement

The Baroque façade does not call attention to itself. It proclaims a message of a higher level. Before you enter the church, it is important to know how to read this front message.

In the church – and also in the Church – everything has to do with Jesus. He – the Saviour, the Redeemer, the Messiah – is symbolised by the big gilded cross on top. That Jesus was prepared to give Himself so much as to die on the cross, was stressed in some sketches by Rubens, in which life size angels occur on the fronton. At the far left and right an angel holds an instrument of Jesus’ passion in his hand: the right one three nails of His crucifixion, the left one the lance His heart was pierced with to ascertain death. A third angel would support the cross on top of the façade. However, they remained but sketches.

This Jesus has been sculpted plastically once (by Hans van Mildert) as a child standing on His mother’s knee. He blesses the world, starting with the passers-by on the church square. The gaze of the Madonna enthroned follows this blessing. Because Jesus and Mary are not an ordinary ‘mother and child’ their dignity is accentuated by an elegant canopy, of which the sideways hanging curtain is held up by an angel. In the 17th century the rumour went that this Jesuit’s Madonna could look over the roofs into the Town Hall.

Jesus’ gospelOne of the four books of the Bible that focus on Jesus’s actions and sayings, his death and resurrection. The four evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. ‘Gospel’ is the Old English translation of the Greek evangeleon, which literally means ‘Good News’. This term refers to the core message of these books. is universal and is passed on from generation to generation by all possible means. The first ones to contribute to this were the four evangelists. Initially their life size statues in their niches formed an X-formation in relation to the Christ monogram in the centre.

Originally the main responsible of the Twelve, Peter, and this other great apostleThis is the name given to the principal twelve disciples of Jesus, who were sent by Him to preach the gospel. By extension, the term is also used for other preachers, such as the Apostle Paul and Father Damien (“The Apostle of the Lepers”). Paul, also in niches, flanked Jesus’ name in the central escutcheon. Both apostles are often named in one and the same breath, such as for instance in St.-Pieter en St.-Pauwelstraat (Saint PeterHe was one of the twelve apostles. He was a fisherman who, together with his brother Andrew, was called by Jesus to follow Him. He is the disciple most often mentioned In the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. His original name was Simon. He got his nickname Peter (i.e. rock) from Jesus, who, according to tradition, said that He would build His Church on this rock. and Paul Street) nearby. The Roman Catholic Church is pre-eminently the apostolic church, as it is formulated in the Profession of Faith. This means that its existence and functioning are rooted in the mission of the 12 apostles and in the apostolic succession of popes. The devotion and the mission of Jesus’ apostles, the first companions of Jesus, do form an important keynote for the spirituality of Ignatius, the founder of the order.

Although the six life size statues were hurled down during the French Revolutionary Rule, the corresponding symbols in relief remained in the façade. But the two evangelist symbols at the ground floor were an easy prey for destructiveness. Unfortunately, the 19th century restorers interpreted the damaged winged heads of Mark’s lion and Luke’s ox as angels’ heads. And because angels do not belong to the evangelists Mark and Luke, the new statues of the evangelists were put next to the central medallion on the first floor and consequently both apostles came to stand next to the main porch. The result of this confusion is to be seen till today. A 17th century etching shows that there is no doubt that the apostles Peter and Paul used to be at the first floor. They can clearly be recognized by their attributes: the keys and the sword. Also, the evangelists Mark and Luke on the ground floor can be identified because of their writing pose. The 19th century restorers could easily have avoided their mistake by poring over this etching, which was commonly known.

The four evangelists can be identified by their personal attributes on their bases. Except for Mark they all hold something that refers to writing in their hands. Their current position is as follows:

- top left, John looking up as a sign of an even stronger heavenly inspiration, with an eagle

- top right, Luke with an ox

- bottom right, Mark as an orator pointing upward, with a lion

- bottom left, Matthew with an angel

For the bust of Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, we must look up once again. In fact, the Jesuits wanted this church to be the very first one devoted to him. In the Roman Catholic vision, a church is first of all meant as a house of God, i.e. a space where a community celebrates God, who has revealed himself especially in His Son Jesus. Besides, houses of prayer are also assigned a patron saintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs., a salutary person who is considered a model and protector; in this way God’s assistance is made more tangible. For the patronage of a church only people the church has canonized officially are appropriate. Such a canonization is done in different stages; you must be beatified first. When the church was consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words. in 1621, Ignatius had not been canonized yet and so the Jesuits had to appeal to an official saint. They soon chose Jesus’ mother, Mary, who plays a very important role in Ignatius’ spirituality. That is why the Madonna and child are enthroned in the fronton of the façade, whereas underneath we can see Ignatius’ bust, which was originally made in marble, white (the head) and black (the cassockA long, usually black, garment that reaches down to the feet and is closed at the front from bottom to top with small buttons. Synonym: soutane.): two monumental angels laurel him, as happened before with a Roman triumphator. Exactly one year later Ignatius was canonized and since then the church was known as Saint Ignatius Church (orally abbreviated to ‘Saint Ignatius’), the first one by that name. One can wonder if the sculptures would have been different if Ignatius had been canonized earlier: without Our Lady and Child?

The fact that on the cartouche below Ignatius’ bust we can read a ‘B’ of Beatus (beatified) has nothing to do with his official status at that time, because only one year later, at the occasion of his canonization, it could already be replaced by the higher status of ‘saint’ (Lat. sanctus). As happened also in other orders before the Second Vatican CouncilA large meeting of ecclesiastical office holders, mainly bishops, presided by the pope, to make decisions concerning faith, church customs, etc. A council is usually named after the place where it was held. Examples: the Council of Trent [1645-1653] and the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965], which is also the last council for the time being., among each other the Jesuits talked about their founder as “our blessedUsed of a person who has been beatified. Beatification precedes canonisation and means likewise that the Church recognises that this deceased person has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. Like a saint, he/she may be venerated (not worshipped). Some beatified people are never canonised, usually because they have only a local significance. fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. (Ignatius)”. ‘Blessed’ (Lat. beatus) means ‘in heaven with God’ and so ‘worth honouring’. But because the Jesuits direct themselves from this façade to a broad public, ‘noster’ (our) is left out and what remains is “BP.IGNs” (Beatus Pater IGNatius).

Anyway, thanks to Ignatius the Jesuit order is there and they have their blazon right in the middle of the façade, which is even more striking by the contrast between the gilded letters I H S on the black background. According to the original Greek version they are three letters of the name Jesus (IHSOS). According to the Latin version, which is more current in Western Europe, they are the initials of the creed that Jesus is the saviour of all men: Jesus Hominum Salvator. That Jesus could only save humanity from the powers of evil and death by sacrificing Himself on the cross – and rising from the dead – is illustrated by the combination of His name and a few instruments of the passion: the cross above the crossbar of the ‘H’, and underneath three nails for His wounds: two for the wrists and one for the crossed feet. With this emblem the Jesuit order, alias the Company of Jesus or Societas Jesu, wants to express their identity and their devotion to Jesus. All over the world Baroque Jesuit churches can easily be recognized by this emblem. In Antwerp, no one less than the artist of that time, P.P. Rubens, was asked to design it. More than anybody else he succeeds in drawing the attention to this emblem playfully, with floating angels triumphantly flocking around the escutcheon.

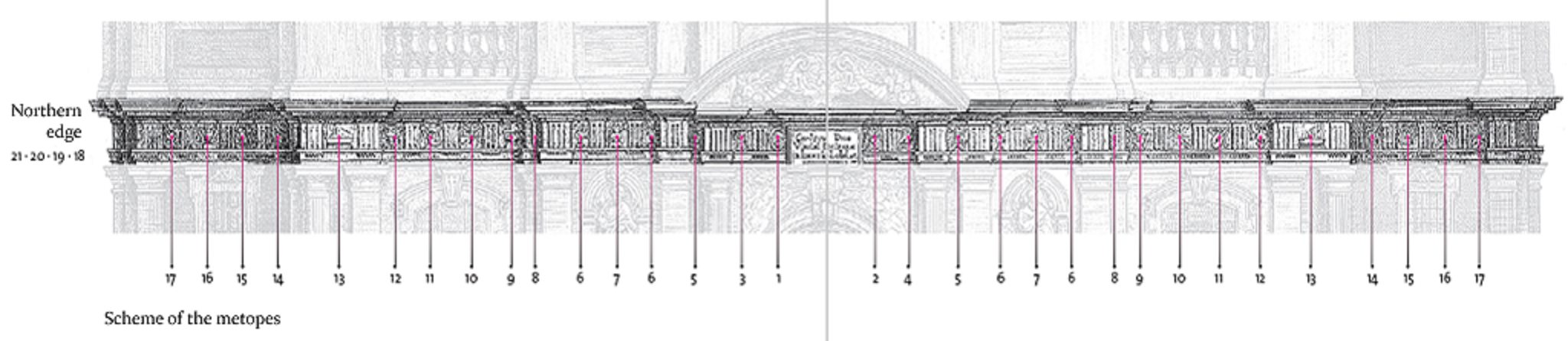

On the spandrels of the main porch two herald angels blow the trumpet: ‘Come here! Something is going to happen here!’. They invite you and get you in the (right) mood to enter the house of God, filled with joy, looking forward to the encounter with His Son Jesus. This encounter is mainly experienced in the EucharistThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live. and this is what the liturgical implements on the metopes of the frieze of the first section refer to.

- The most important ones, used by Jesus himself at the Last Supper, are right above the entrance door: the chaliceGilded metal cup, usually on a base, which the priest uses for the wine during the Eucharist. (1) (2), the cup for the wine, and the patenSmall, gilded metal plate on which the host used by the priest during the Eucharist is placed. (2), the dish for the bread.

Other utensils for the Holy MassThe liturgical celebration in which the Eucharist is central. It consists of two main parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The main parts of the Liturgy of the Word are the prayers for mercy, the Bible readings, and the homily. The Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the offertory, whereby bread and wine are placed on the altar. This is followed by the Eucharistic Prayer, during which the praise of God is sung, and the consecration takes place. Fixed elements are also the praying of the Our Father and a wish for peace, and so one can symbolically sit down at the table with Jesus during Communion. Mass ends with a mission (the Latin missa, from which ‘Mass’ has been derived): the instruction to go out into the world in the same spirit. are:

- (3) the ampullas, the small jugs for the wine and the water that are poured into the chalice. After all wine is not drunk straight: to water down wine is common practice in warmer regions. Later this daily life habitGeneral name for the typical clothing of a particular religious order.

A long-sleeved, unbuttoned robe down to the feet, usually with a hood attached. This attire is typical of monks and nuns.

was interpreted as a symbol of Jesus Christ’s divinity and humanity mixed in His one person. Or as a reference to His passion, when he was sweating water and blood in His agony in Gethsemane (Lk. 22:44). And did there not flow water and blood from His pierced side after His crucifixion (John 19:34)? - The carafe with basin and towel (4) is used for the ‘lavabo’, the ritual washing of the priest’s hands.

- A censor (7) and an incense boat (20). Catholic tradition likes involving natural elements into rituals. The evoking power of these primeval symbols keeps appealing, even when used quite minimally. The fire makes the flavours of solidified tree saps ascend in sacred smoke. A probing act that wants to make God’s transcendence tangible.

- (8) A holy waterWater that has been consecrated during the Easter vigil and which is used for baptisms and ritual blessings. bucket and aspergillum. With holy water, the faithful cross themselves when entering the church, and at the beginning of the solemn Eucharist the priestIn the Roman Catholic Church, the priest is an unmarried man ordained as a priest by the bishop, which gives him the right to administer the six other sacraments: baptism, confirmation, confession, Eucharist, marriage, and the anointing of the sick. sprinkles the faithful with holy water. The holy water reminds us of baptismThrough this sacrament, a person becomes a member of the Church community of faith. The core of the event is a ritual washing, which is usually limited to sprinkling the head with water. Traditionally baptism is administered by a priest, but nowadays it is often also done by a deacon., by which the faithful are purified and called to live as children of God.

- (11) A sanctuary lampOil lamp placed near the tabernacle to indicate the presence of consecrated hosts. In the past this was usually a lamp suspended from three chains. Nowadays it can also be a table lamp. Usually, the sanctuary lamp has a red glass to distinguish it from ordinary candles.. To draw the faithful’s attention to God’s permanent presence an oil lamp in a red glass burns by the holy consecrated bread in the tabernacleA small cupboard in the choir or in a specially designated chapel in which the consecrated hosts are kept. day and night.

- As part of devotional scenery there are candelabras (5), candles (5) (9) and small flower vases (6) (16)

- (Biblical) lectures can be found in the lectionaryA liturgical book holding the epistles and Gospel readings to be read at Mass according to a fixed schedule. The Gospel reading forms the basis, and the epistles complement and/or parallel it. It concerns a three-year cycle: in the A-year from Matthew’s Gospel, in the B-year from Mark’s Gospel and in the C-year from Luke’s Gospel. Texts from John’s Gospel are spread over the three years. (15), the liturgical texts in the prayer book (16), supported by a cushion.

That the faithful experience the Eucharist as a festive event is brought into vision by musical instruments on this same frieze. Thus, several stringed (10) (14) (17) and wind instruments (13) (17) (21) can be noticed, as well as a positive organ (12) and scores (18) (21).

Notice that one side of the façade is nearly the mirror view of the other one. Only at the northern side there are a few metopes more (nbs. 18-21).