Antwerp's St Andrew's Church, a revelation.

A building history of five centuries

By the end of the Middle Ages, the city of Antwerp had become home to a considerable number of monastic communities. Before 1511, Augustinian monks had acquired a spacious plot of land on the Boeksteeg (current Nationalestraat). The first chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

built by the monks at this site was completed in 1513 and dedicated to the Holy TrinityThe concept that there is one God who shows himself in threefold form: Father, Son (Jesus of Nazareth) and the Holy Spirit.. By 1514, however, large audiences gathering for some of the order’s rather popular preachers compelled the monks to begin the construction of a bigger church.

While studying at the German town of Wittenberg, the priors and brothers of the Antwerp monasteryComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. witnessed the critical preaching of a fellow Augustinian monkA male member of a monastic order who concentrates on a life of balance between prayer and work in the seclusion of a monastery or abbey., Martin Luther. In 1517, Luther published his famous ‘Theses’ in Wittenberg. In Antwerp, the Augustinian monastery pioneered as the city’s first venue for reformist preaching, especially through the work of the monastery’s prior – and friend of Luther – Jacobus Praepositus (whose original name was Proost). A question frequently asked by the town’s citizens during this period was “Wat geloove heddij, prekers- oft augustijnsgeloove?” Bearing witness to the religious situation, the question translates as: “What do you believe, the faith of preachers or that of Augustinians?” The ‘preachers’ belonged to the Order of Preachers: the Dominicans, who defended and preached catholic orthodoxy as explained by the teachings of Dominican monk Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). In contrast, many of the Augustinian monks at the time strongly adhered to Luther’s teachings.

Only a decade after the order’s establishment in Antwerp, the Augustinians were taken into custody on account of their Lutheran sympathies. It should be noted that this arrest was not supported by the bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’., who still resided in Cambrai at the time. Instead, the decision was authorised by Emperor Charles V, who considered it his political duty to safeguard orthodoxy. At the time of the arrest, the naveThe rear part of the church which is reserved for the congregation. The nave extends to the transept. of the Augustinian church had not yet been completed.

From the rood screenA (usually decorated) screen that separates the choir or chancel from the transept and the nave. This makes the chancel an enclosed chapel within the church. On the rood screen there is usually a triumphal cross and sometimes an organ. In Antwerp, St. James’s still has such a rood screen and a little further away, in Lier, St. Gummarus’s church. of the Church of Our Lady, most Antwerp Augustinians finally renounced Luther’s teachings. Yet some monks continued to preach reformist beliefs to great acclaim, a.o. in the Mint building.

Unwavering reformists Hendrik Voes and Jan van Essen were burnt at the stake on the Great Market of Brussels on 1 July 1523. On 6 October of the same year, Margaret of Austria ordered the Antwerp monastery to be abolished. When Luther learned about the death of his fellow brothers, he composed and dedicated the song with rhyming verse “Eyn newes lied wyr heben aan…”.

The humanist thinker Desiderius Erasmus, who had before voiced his admiration for the authentic character of the Augustinians’ preaching, now, however, condemned the monks’ ‘errors’.

The church building was now designated a forbidden area, and the plot was walled in. The district’s landowners, who had hoped that the church’s presence would increase the neighbourhood’s land value, were reluctant to see the completed parts of the building fall to ruin. The developing quarter needed a new, independent parish church, and the landowners proposed that this place of worship was to be completed. Permission was granted through the city councilA large meeting of ecclesiastical office holders, mainly bishops, presided by the pope, to make decisions concerning faith, church customs, etc. A council is usually named after the place where it was held. Examples: the Council of Trent [1645-1653] and the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965], which is also the last council for the time being., by governess Margaret of Austria and Pope Adrian VI. As SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Andrew was also patron saint of the House of Burgundy, the parish’ new patron saint has often been thought to have been adopted as a token of gratitude toward the governess. In this account, however, the latter’s role is probably given more weight than it actually carried. Although Margaret of Austria did sign the required documents, she may not have taken the actual initiative. Historians are often tempted, though, to make ‘clean’ causal connections between historical events and well-known historical figures.

In 1527, the monastery’s grounds were sold and parcelled out in order to finance the church’s construction. In 1529, the church was ready to use. Promptly, the parish was canonically established; one week later, on the 6th of June, the church was consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words.. A year later, eight side altars were consecrated as well.

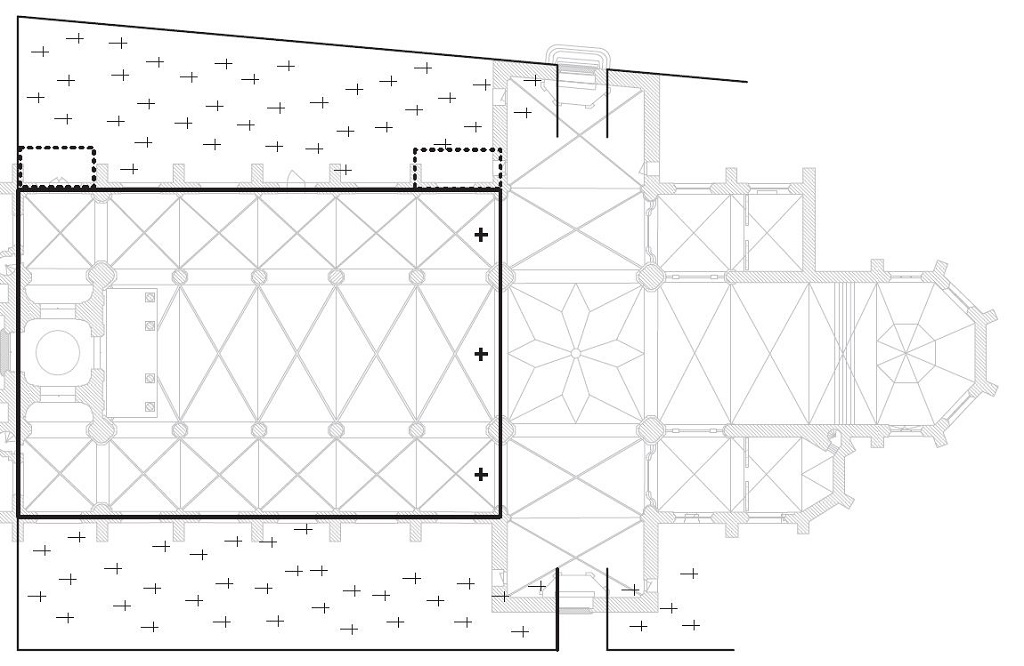

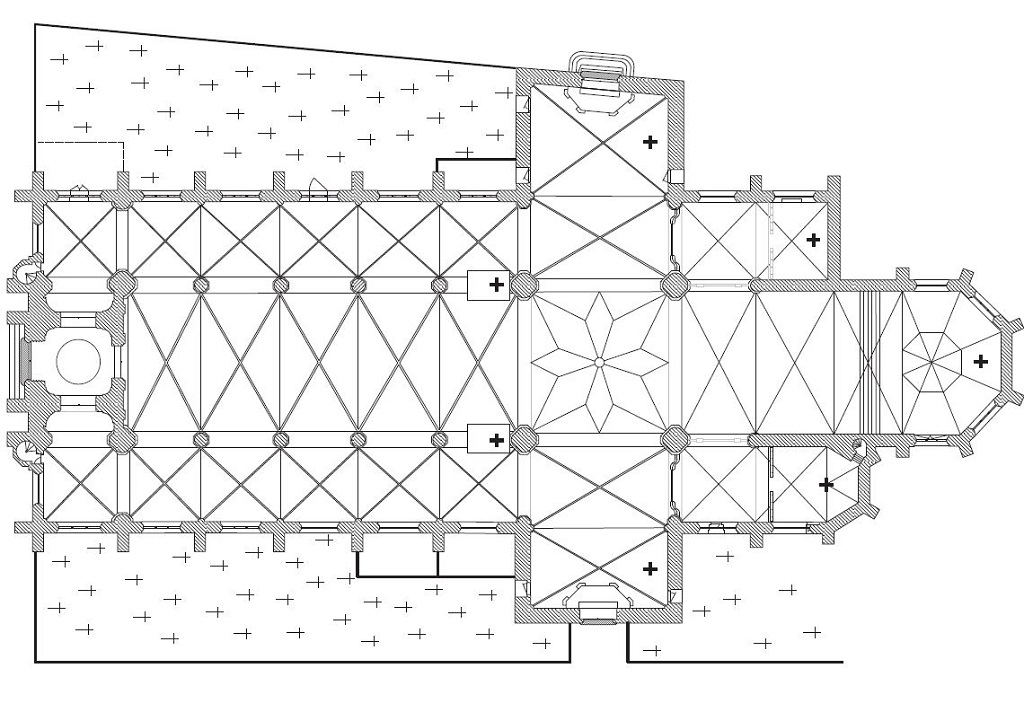

Later on, the church’s west side was embellished with a tower; further, the building was extended with a transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right.. The Augustinian monks hadn’t considered such architectural elements, which were unnecessary for a modest monastery church. As such, it is also assumed that the vaulted aisles were only constructed after 1529. To finance such expenses, Charles V allowed for the organisation of a lottery. In 1559, the tower was finally adorned with a pear-shaped crown. Devotional fraternities in particular contributed to the artistic decorations, by constructing and adorning altars.

The church’s furniture – including the organ – was smashed to pieces during the destructive frenzy of the first Iconoclastic Fury in 1566. By the end of 1578, Antwerp was under Calvinist rule, and the city’s religious politics were mirrored in the church building, where a wall divided the space between Catholics and Calvinists. The three-aisled nave distinctly resembled a ‘room’ and housed the church’s pulpit. This part of the church was therefore assigned to the Calvinists, who underlined the importance of the proclamation of the Word of God. As Catholics greatly valued liturgical celebration, they were assigned the church’s choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. and transept, which contained several altars.

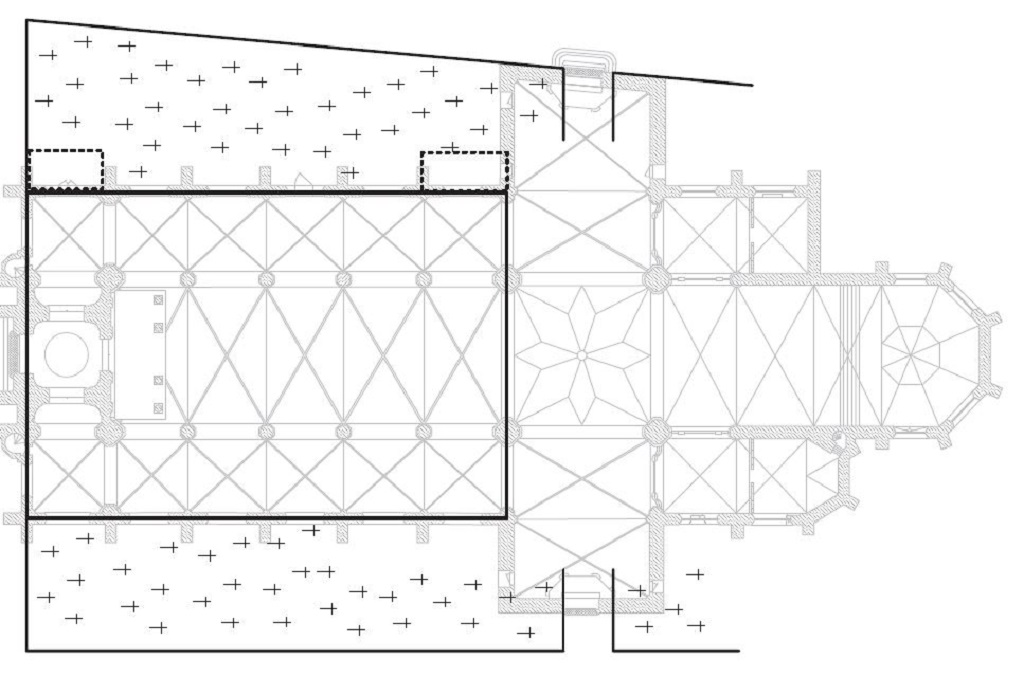

Two years later, in 1581, this separation wall became even more useful, as Calvinists abolished Catholic services altogether. Consequently, Calvinist believers razed the ‘superfluous’ choir and transept to the ground. This ‘thorough’ approach sought to prevent any possible return of Catholic believers. In effect, the 1581 ‘church cleansing’ of St Andrew’s surpassed the brutal destruction of fifteen years earlier.

In 1585 the tables were turned. Representing the legal Spanish authorities, Alexander Farnese succeeded in recapturing Antwerp; immediately afterwards, Catholic believers reclaimed the church. The Gothic church building had been halved and was now furnished with painted altarpieces, in late Renaissance or Mannerist style. The churchwardens commissioned an altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. by Otto van Veen for the main altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine.; Maerten de Vos began working on the minters’ altar. A member of the district’s large Francken family furnished the Holy Cross altar and the Venerable altar. By the time of Rubens’ return to Antwerp in 1608, the entire church building had already been decorated by these ‘modern’ masters. Therefore, the churchwardens did not commission any further altarpieces, not even from Rubens – even though the master-painter did reside in the parish of St Andrew’s for a while. He married in the abbatial church of St Michael, but his first children were baptised in the parish church.

Several memorial statues were completed in early and high Baroque style, including the funeral monument of Mary Stuart’s ladies-in-waiting (1620), by an unknown artist; and the one for canonSomeone who, together with other canons, is attached to a cathedral or collegiate church and whose main task is to ensure choral prayer. Peter Saboth (ca. 1658), by Artus Quellinus the Elder.

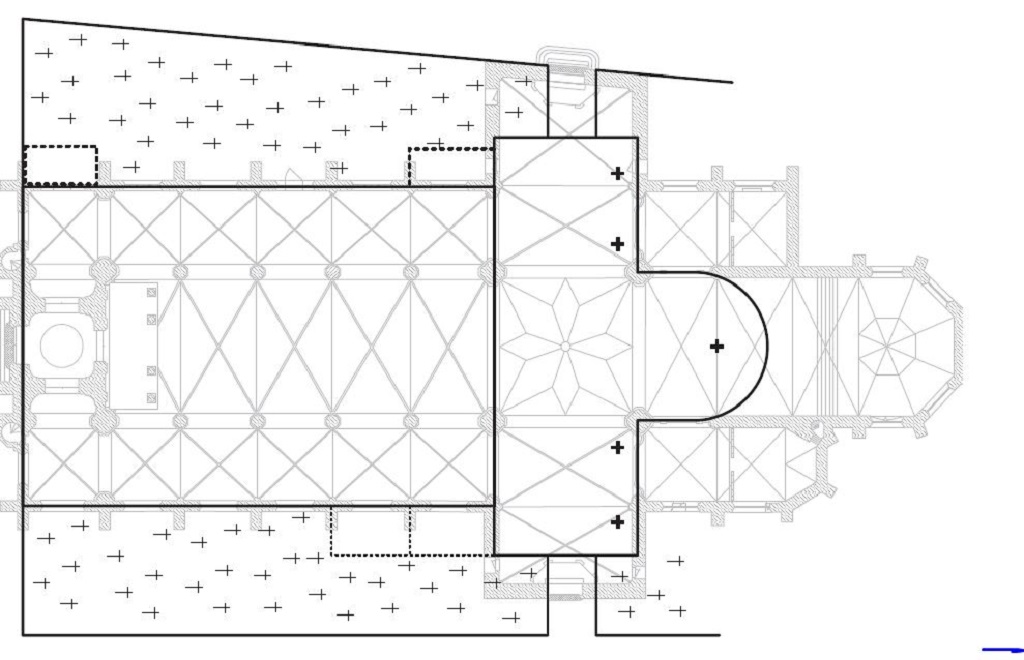

After over half a century of planning, a great building campaign started in the middle of the 17th century. First the nave was vaulted in 1659-1661, an addition which finally improved the building’s fire safety. In 1663 the transept – which had been pulled down by the Calvinists – was restored and expanded. On the building’s north side, the churchyard reached only up to the side aisleLengthwise the nave [in exceptional cases also the transept] of the church is divided into aisles. An aisle is the space between two series of pillars or between a series of pillars and the outer wall. Each aisle is divided into bays.; now, the transept was extended right up to the side of the street. On the south side, the churchyard extended further towards the east; the south transept extension was somewhat shortened, so as not to divide the yard. These transept extensions ‘upgraded’ both first pillars of the eastern nave to crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept]. pillars once more.

Once the Calvinists’ separation wall had been torn down, the Venerable altar and the altar of Mary were relocated from the aisles to the (provisional) eastern transept wall. Later that year, bishop Ambrosius Capello consecrated the transept. In 1664 the main altar was moved to the new choir. By relocating the three most important side altars, it became possible to move the altars of the Holy Cross (1664-1665) and St Anne (1673-1674) to the first eastern pillars of the nave: a place of greater importance, too.

In 1666 the Holy SacramentIn Christianity, this is a sacred act in which God comes to man. Sacraments mark important moments in human life. In the Catholic Church, there are seven sacraments: baptism, confession, Eucharist, confirmation, anointing of the sick, marriage and ordination. chapel association began constructing a separate devotional space, which in 1678 was followed by the construction of the Mary Chapel. Since 1683, consequently, the church choir (two bays long) was flanked by both chapels. Each chapel was furnished with its own sacristyThe room where the priest(s), the prayer leader(s) and the altar server(s) and/or acolyte(s) prepare and change clothes for Mass.. In 1685-1686, the transept was vaulted with a star vault at the crossing.

During this period, plans were made to extend the choir even further. A round tempietto (an exceptional architectural feature within the context of the Low Countries) would be constructed to highlight the altarpiece Apotheosis of Holy Andrew. Six design sketches (signed by Hendrik Frans Verbruggen) remain; yet the project itself was never realised.

In 1755, the collapse of the dilapidated tower of the church of St Andrew attracted widespread public attention. Although the tower had been shored for a while by this time, the support evidently proved insufficient.

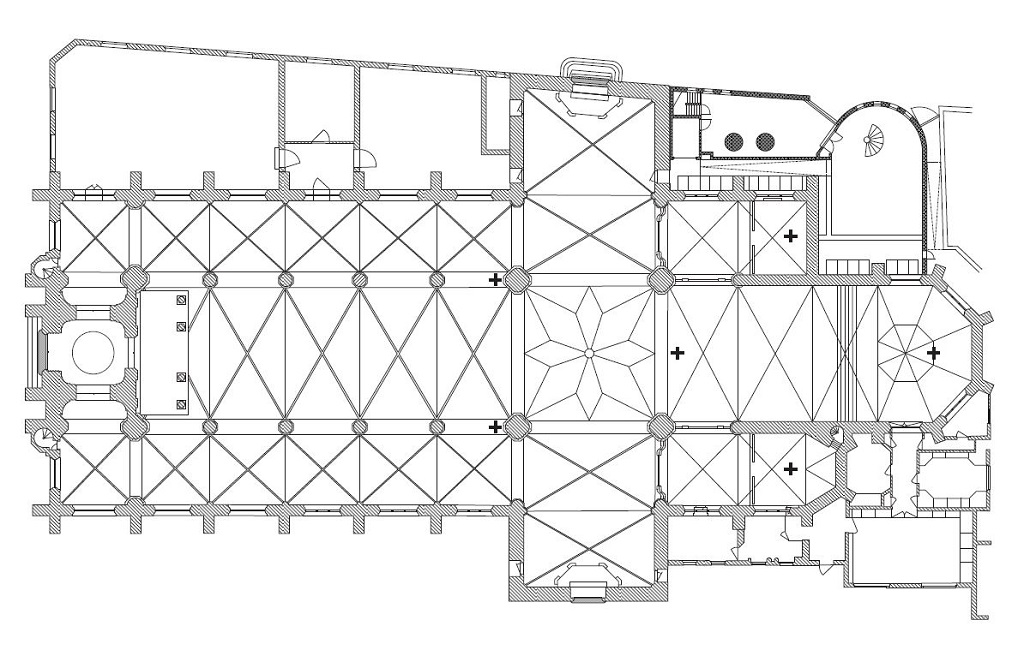

Collapsing onto the three western bays of the south nave, the tower destroyed graves and funeral monuments in this part of the church, as well as the rood screen and the nave’s organ. The bays of the south nave were reconstructed in modern bluestone and can still be recognised by the distinctive grey colour of the ribs.

A year later, construction started on a late Baroque tower, designed by master builder Engelbert Baets. This new tower was positioned entirely within the western bayThe space between two supports (wall or pillars) in the longitudinal direction of the nave, transept, choir, or aisle. of the nave; as such, the two nave pillars could be used as extra abutments to support the church’s weaker interior walls. It took until 1763 (seven years of work) to complete the 58 metre tall tower, which was topped with a double roof lantern, a pair of wooden open copulas. The architect would use this type of spire crowning again for the BasilicaA rectangular building consisting of a central nave with a side aisle on each side. On the short side opposite the entrance, there is a round extension, the apse, where the altar is located. The Antwerp Saint Charles Borromeo church is based on this basilica structure.

An honorary title awarded to a church because of its special significance, for example as a place of pilgrimage. There are 29 basilicas in Belgium, the best known of which are the Basilica of Scherpenheuvel and the Basilica of Koekelberg. Worldwide this is Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. These churches do not have the architectural form of a basilica.

of Our Lady in Halle, some 10 miles south of Brussels.

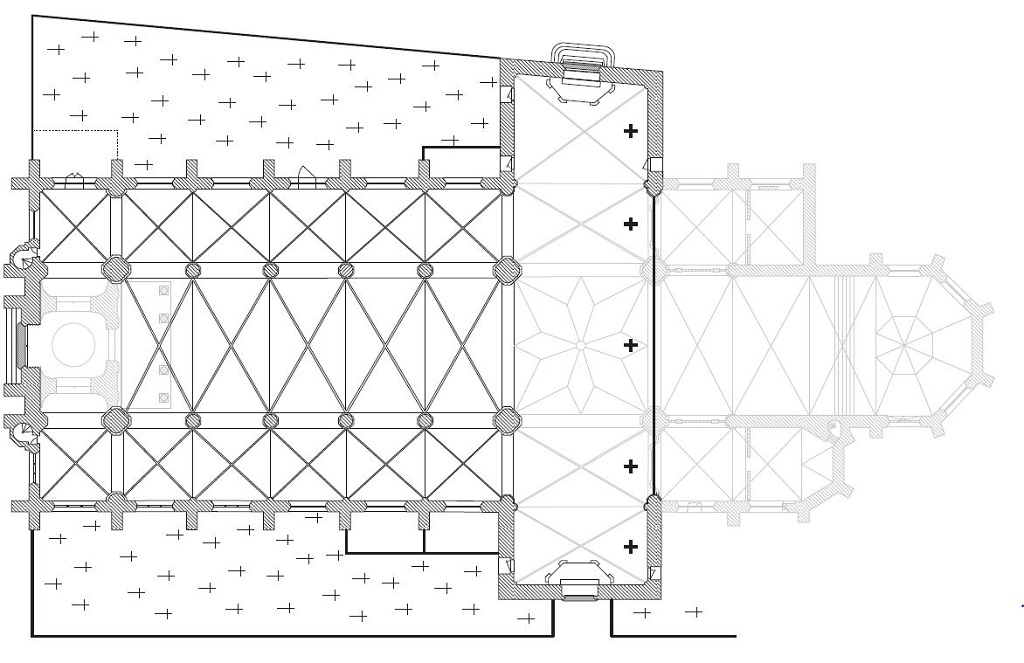

Immediately after the tower had been completed, the characteristic 18th century bluestone grey was used again for the extension and vaulting of the choir (1765-1769). The contractor’s name, which had been chiselled in the wood of a 1763 tower beam, was now carved in one of the attic beams as well: “ANNO . 1766 . DEN . XIII . 7BER // . A.V. BUSSEL” (“In the year 1766, on the 13th of September // Adrian Van Bussel”). Why, one wonders, did mid-18th century architects and constructors still go to such lengths to create this gigantic choir space? Indeed, as a normal parish church, St Andrew’s did not hostA portion of bread made of unleavened wheat flour that, according to Roman Catholic belief, becomes the body of Christ during the Eucharist. any regular(Adj.) This is said of a priest who is a member of a religious order and therefore submits to the rule of this order and owes obedience to the superior of his (monastic) community. canons or clerics and was therefore not in need of choir stallsA series of seats, usually in wood, along the long sides of the choir. These seats are reserved for those who pray and sing the choir prayers.. Did the Baroque desire for decorum perhaps require such immense, theatrical space? At any rate, no expense was spared; even the small passage to the parsonage, and a school building at the east side of the church had to make way.

The late Baroque design sketch for this choir space (possibly by the Augustine brotherA male religious who is not a priest. Alipius) depicts a boarding with oculi windows in the light vault and round arch windows on the ground floor. A round arch can be found too on the two opposite doors, one leading from corridor to sacristy and one to the current tabernacleA small cupboard in the choir or in a specially designated chapel in which the consecrated hosts are kept.. Eventually, this design of a Baroque high altar was abandoned too. However, the main altar with the Van Veen painting in its apseSemi-circular or polygonal extension where the high altar is located in a church. was flanked by both the statue of St Peter by Artus Quellinus the Elder and its new pendant: the Statue of St Paul by Jozef Gillis.

In 1794, the war tax imposed by the French effectively forced the church of St Andrew to part with great quantities of its church silver. Upon seizure of the church in 1798, two of its most beautiful artworks were confiscated: Maerten de Vos’ triptych for the minters’ altar, and the statue of St Peter by Artus Quellinus the Elder. And that was the end of it. For in contrast to St George’s, the neighbouring parish church that was sold and torn down, St Andrew’s, remarkably, survived the French Revolutionary Rule.

The new French constitution expressed faith in God as the Supreme Being, but regarded Him solely as the reasonable, intelligent Mind that had created everything. The revolutionaries banished the central idea of Christian faith – that God is Love – to the realm of myth. They denied the meaning of building a relationship with God through prayer, even less through community during religious service. Seeking to encourage people to partake in more ‘useful’ activities, the revolutionaries decided on principle to close all churches in 1797.

In order to protect their political legacy, however, the revolutionaries allowed for some religious concessions. Every priestIn the Roman Catholic Church, the priest is an unmarried man ordained as a priest by the bishop, which gives him the right to administer the six other sacraments: baptism, confirmation, confession, Eucharist, marriage, and the anointing of the sick. who publically swore the Oath of Hatred of Kings was allowed to keep any church he wished in return. But the Catholic Church remained firmly opposed to the revolutionary rule and was prepared to pay a huge cost to remain faithful to its principles. According to the Church, God’s kingship constituted the sole legal authority at the time; His kingship couldn’t be recanted. It would be unthinkable, moreover, for Christian believers to swear any oath of hatred. Thus, the parish priestA priest in charge of a parish. Alexander Van der Stallen was sentenced to be deported, as were most Antwerp priests who held true to the ecclesiastical point of view. In 1799, Van der Stallen was arrested and taken into custody, but he escaped from the citadel hidden under a cattle farmer’s grass cargo. The cattle farmer was a parishioner of St Andrew’s; Van der Stallen hid and continued to serve the parish in secret.

However, priest Jan-Michiel Timmermans was prepared to swear the Oath of Hatred. In doing so, he saved both himself and a church under threat. Indeed, in 1798 Timmermans chose the church of St Andrew as a reward for his Oath; the other ‘sworn priest’ in Antwerp, Mortelmans, chose the church of St James. Timmermans’ choice was ill received, both by the ecclesial authorities, who refused to recognise him as a parish priest, and by the people, who sympathized with the oppressed clergy. However, Timmermans’ disobedience to the church, and his obedience to state rule, ensured the continued existence of the church of St Andrew, including its art treasures, up until today.

Following the 1801 Concordat between the Holy See and Napoleon, the church of St Andrew became a parish church once more. The building had remained virtually intact. The abolished bishopric of Antwerp was added almost in its entirety to the archbishopricThe bishop in charge of the archdiocese. In actual practice, this also means that he is the head of the church province. of Mechelen; from now on, parish priests would be appointed there. Parish priest Alexander Van der Stallen was officially reinstated on 2 May 1803. In the same year, the statue of St Peter by Artus Quellinus the Elder was returned to the church. The triptych by Maerten de Vos, however, would remain at the Academy Museum. The sober church interior was to be decorated further in Baroque style, which was still in vogue at the time. The main altar and pulpit – the church’s two most prominent artworks – date back to this period.

Initially, and partly still under French Rule, artworks were recuperated from abolished Antwerp churches. The demolition of the neighbouring church of St George caused the parish grounds of St Andrew’s to be extended significantly towards the south. Moreover, St Andrew’s became heir to the old church of St Philip at the Spanish castle. As such, the church acquired several exceptional antependia in high Baroque style. Further, St Andrew’s became home to devotional pieces from abolished neighbouring monasteries, such as the relics of the 36 Saints from the AbbeyA set of buildings used by monks or nuns. Only Cistercians, Benedictines, Norbertines and Trappists have abbeys. An abbey strives to be self-sufficient. of St Salvator and the statue of Our Lady of Peace and Harmony from the Abbey of St Michael. The churchwardens proceeded to buy the imposing main altar of the former Abbey of St Bernard in Hemiksem, the Augustine Monastery’s choir stalls and the Alexians’ tabernacle door. From the church of the Calced Carmelites on the Meir came communion railA low enclosure of the choir or a chapel in the form of a long kneeling pew. Before the Second Vatican Council, it was customary to receive communion kneeling on at this pew. panels and a holy waterWater that has been consecrated during the Easter vigil and which is used for baptisms and ritual blessings. fontA small basin at the entrance of a church, containing holy water so that the faithful may sprinkle themselves with it when entering the church, while making the sign of the cross, as a symbol of outward and inward cleansing., which would henceforth serve as the church’s baptismal fontThe stone or metal vessel containing holy water, used for administering baptism. Often the baptismal font is/was located in a specially designed baptistery, usually close to the entrance of the church..

Subsequently, assignments for artworks were given to artists, who, up until the middle of the 19th century faithfully adhered to the Baroque style. In 1821, the Renaissance pulpit was replaced by a pulpit in late Baroque style, unparalleled even in the Southern Low Countries before the French Revolution. The singing tribune (1828-1829) and the voluminous silver relicA remnant of the body of a saint or a (part of) an object that has been in contact with a saint, Jesus, or Mary. The very first sanctuaries were built on graves of saints. Remnants of these saints were distributed to other churches and chapels. The first altars were usually the sarcophagi of the saints. Hence the custom of placing relics under the altar stone. Relics are also kept in shrines, and sometimes displayed in reliquaries. shrineA decorated casket in which a relic is preserved. of the 36 Saints by Jan Verschuylen (1845) demonstrate a more classicist Baroque style. Further, the new garments for the statue of Our Lady of Sustention and Victory also expressed the desire for abundant Baroque decorum.

The first stationOne of the fourteen stages of the Way of the Cross: Jesus is sentenced to death.

Jesus takes up the cross.

Jesus falls the first time.

Jesus meets His mother.

Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry the cross.

Veronica wipes Jesus’s face.

Jesus falls the second time.

Jesus comforts the mourning women.

Jesus falls the third time.

Jesus is stripped naked.

Jesus is nailed to the cross.

Jesus dies.

Jesus is taken down from the cross.

Jesus is laid into a tomb.

of the new way of the cross was painted in 1845. Only by 1857 was the entire sequence of fourteen stations complete. The large paintings were mounted in heavy decorative frames and hung in a colourful cycle across the church.

In 1855 the stained glass window by Jan-Frans Pluys in the Mary Chapel was completed – the beginning of a long series of neo-Gothic stained glass windows for the church. A glimpse of this first window can still be seen in the oldest painted church interior of St Andrew’s, a painting by Eugénie Van Haverbeke (1857). Between 1863 and 1917, a succession of glaziers working in neo-Gothic church style made the church bathe in an unseen wealth of colour: Jean-Baptist Capronnier, Henri Dobbelaere, Jean-Baptist Bethune, PetrusHe was one of the twelve apostles. He was a fisherman who, together with his brother Andrew, was called by Jesus to follow Him. He is the disciple most often mentioned In the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. His original name was Simon. He got his nickname Peter (i.e. rock) from Jesus, who, according to tradition, said that He would build His Church on this rock. De Craen and the studio of August Stalins and Alfons Janssens. In a grand gesture motivated by the same neo-Gothic desire, parapets were added to the upper windows in 1868.

In 1889, the explosion of the Corvilain gunpowder factory in Oosterweel caused great damage to the church – as it did to many other buildings. Almost all new stained glass windows on the church’s north side were destroyed. Not until the First World War would most windows be replaced.

During the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, fraternities were thriving – at times, such societies counted thousands of members. In honour of their celebrated saints, these fraternities adorned the church interior with occasional decorations, transforming it into an extensive scenery for spectacles.

In 1929, the 400-year jubilee of the parish church was celebrated with a lot of circumstance. For the first time, the so-called Boat of Amalfi (the silver relic shrine of holy Andrew, by Jos Junes) was included in the procession. The organ was electrically pneumatised; a real symphonic concert was organised on the tower; and an illustrated church guide was published, the first of its kind in Antwerp. One year later, the choir was equipped with floor heating.

Een jaar later komt er in het koor vloerverwarming.

In 1938, the church of St Andrew and its furniture and art works were listed as a monument. Yet this status could not offer protection against the horrors of war. On 2 January 1945, near the end of the Second World War, 19 civilians fell victim to the impact of a V-bomb dropped on Friday Market. Once again, nearly every stained glass window on the church’s north side was destroyed. The church interior was covered under a layer of snow; the angels of the Mary chapel’s confessionalA piece of furniture that was especially designed to facilitate the sacrament of confession, especially by avoiding that confessor and penitent come face to face. To the left and right are kneeling pews for penitents; in the middle is a small booth where the confessor sits. Both are separated from each other by a partition with a grid, so that the confessor can hear the penitent, but cannot see him / her. appeared to be dressed in fur coats.

To prevent a (partial) repetition of the 1755 scenario, the dilapidated wooden tower lantern was wisely pulled down in 1961. The tower was then securely rebuilt in 1970-1975, constructed partly out of concrete.

Ten stained glass windows by Jan Huet (paid for so as to compensate war damages) ensured that the church has been bathing again in colour since the 1960’s. But parishioners could not enjoy these windows for very long: from 1970 until 1975, the church was closed for major restorations. Following the sudden postponement of the restorations’ fourth phase (which included the church’s central heating and the annexes), even the subsoil under the Mary Chapel became saturated with rainwater. Then, in 1983, the Chapel’s century-old sacristy collapsed and was irretrievably lost; so were its oak cupboards. After extensive administrative agony, the creation of the current museum and boiler room began in 2002.

From 2000 onwards, contemporary views on old art have given shape to the church as a playful space for art and spirituality for young and old alike. On the one hand, the church seeks to valorise its undervalued heritage in different ways: firstly, the acquisition of works of art that are directly ‘related’ to the church, such as the modello for Martyrdom of St Andrew by Otto van Veen, or – more importantly – the acquisition of stolen objects, such as a statue of St Andrew (p. 73). Sometimes, acquisitions of old art ‘from outside’ would elevate the church’s standard of decoration and spirituality, as seen in the wooden communion rails at the contemporary celebration altar.

Further, old works of art are being reconstructed; for example, the minter’s altar, the name panel of the fraternity of ‘Faithful Souls’, the Way of the Cross, and the precious musical instruments of the organ case. The treasury’s thematic layout, and informative texts at the baptismal and death fonts, at the way of the cross, etc., seek to offer further access to, and understanding of, the meaning of the church’s old heritage.

On the other hand, the sober church now provides ample space for modern art. As the church of the 17th-century communicated its message using the style of the times, today’s church seeks to express itself through the 21st-century language of art. Contemporary audiences may feel challenged by, say, the robe for the Mary statue by Ann Demeulemeester and the painting What Is Truth? by Alain Senez. Other creations include: pop-art shoes for the journey of life, a punchbag for those who keep wrestling with God, and a representation of God as a DJ of all things living and moving, between the angelic musicians on top of the baroque organ. Aside a series of recent saints, the spectator can look into a mirror that mirrors the question: Are you next?

The language has changed as well: the international Latin of informative labels has given way to English, which isn’t merely used to accommodate foreign visitors.