The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

The guilds’ altars

Because the guilds had been abolished by the French Revolutionary Rule their belongings were confiscated. As a result most altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine. paintings are now in the KMSKA (Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp). Still the once so close connection between labour, art and faith can still be felt in this church thanks to a few relics, including some extraordinary triptychs.

The tens of Gothic keystones from the second half of the 15th century in the naveThe rear part of the church which is reserved for the congregation. The nave extends to the transept. were meant to be colourful, but unfortunately their original polychromy has gone lost due to the violent restoration methods used in the 1970’s. Even though their iconography does not form a unity, some succeed in telling us for whom the spaces underneath were destined, including numerous guilds. In the uttermost northern aisleLengthwise the nave [in exceptional cases also the transept] of the church is divided into aisles. An aisle is the space between two series of pillars or between a series of pillars and the outer wall. Each aisle is divided into bays. the conic keystone of the second bayThe space between two supports (wall or pillars) in the longitudinal direction of the nave, transept, choir, or aisle. (counting from the West) shows SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Arnold with the emblems and activities of the brewers’ guild. In the one of the third bay we can see scissors of the cloth shearers and in the fourth bay there is a tub of the dyers, to whom they were related. Also the multi-coloured Renaissance vaulting paintings in the aisles are connected with the original users of the altar spaces concerned. So the presence of the brewers in the uttermost northern aisle can also be derived from their coat of arms (after 1533).

In the innermost southern aisle we can find the painted traces of the retailers (Jan Crans, 1538). One of their most important activities was weighing bulk goods that were for sale. This is why an angel lets down a pair of brass scales from a kind of porthole. Their patron saint, Saint Nicholas, can be seen on the boss. As soon as the bay of the bakers, a bit further in the central aisle was vaulted, the keystone was given a relief with their patron saint, Aubert. A year later they had the vaulting around it painted with their emblem: crossed baker’s shovels with a couple of round loafs of bread on them. When after the 1533 fire the bakers’ altar was moved a bay towards the pillar of the central naveThe space between the two central series of pillars of the nave. a similar painting was made in the neighbouring bay of the innermost southern aisle. Of which churchgoer, who then had to keep the rule of fasting before Holy CommunionThe consumption of consecrated bread and wine. Usually this is limited to eating the consecrated host., was not their mouth watering at the sight of these oven-fresh rolls early in the morning at the EucharistThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live.?

In fact these vault paintings are among the ‘most beautiful’ art treasures in the church: people who toil daily for their livelihood are proud of their work and do not hesitate to apply their tools as adornments on the vaultings of their cathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is.. This is a sublime tribute to human labour, which is praised in Heaven. If one does not want to degrade the cathedral into a historic museum of antiquities and retain the same spirit of engagement with daily life, this might be an invitation to create new vault paintings with present-day tools. Present-day man may also feel good at the sense of his daily labour.

The fishmongers’ altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. by Hans van Elburcht, ca. 1560, reflects the devotion for their patron saints: the apostle-fisherman par excellence, Peter, the most important one, is in the central panel and on the left panel of the predellaThe base of an altarpiece. Like the altarpiece, the predella may be painted or sculpted.; the apostles Philip and James the Less are on the wings.

The main scene in the foreground was inspired by a print from 1556 by Pieter van der Heyden, which in its turn goes back to a work by Lambert Lombard. Because it was adapted to a portico altar the triptych was made smaller, probably in 1621, when the fishmongers’ altar was moved to the western pillar of the central nave. Unfortunately we do not know anymore what the complete central scene looked like originally.

The central panel shows in three acts successive scenes from the story of the miraculous catch of fish (John 21:1-14). The story is to be read from the background top left [I] to the middle ground centre right (II) and then back to the foreground on the left [III]

[I] On the initiative of Peter six apostles join him to go fishing on Lake Tiberias, but they do not catch anything. At the apparition of the Risen Christ (✛) on the bank there is a miraculous catch of fish. While the other six apostles do everything they can to hoist the full nets aboard, Peter (A1) wades through the water to Christ.

[III] ‘The other disciples came in the boat’, ‘dragging the net with the fish’. At Jesus’s demand for some of the (miraculous) fish that they have just caught Peter (A1) drags the rich catch ashore.

[III] In the foreground the emphasis is on the supply of the ‘large fish’, which Jesus (✛) gave them in His turn together with the bread. Peter (A1), once again as (second) main character, has knelt in front of Jesus, together with young John (A2) with the blond hair.

The wings focus on the two other patron saints of the guild. The left wing shows the baptismThrough this sacrament, a person becomes a member of the Church community of faith. The core of the event is a ritual washing, which is usually limited to sprinkling the head with water. Traditionally baptism is administered by a priest, but nowadays it is often also done by a deacon. of the Ethiopian eunuch (alias ‘the Moor’) by Philip (Acts 8:26-40) (Rotterdam, Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum). On the right we see the martyr’s death of James the Less (Saint-Ghislain, ConventComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. of the Sisters of Mercy).

In the last quarter of the 16th century, presumably after the restoration of Catholic worship in 1585, the two panels of the predella were added, by an anonymous artist probably from the surroundings of Ambrose Francken. Here Jesus invites fishermen to follow him: they will be the first apostles. On the left panel (iconographically right) with The calling of Peter at the miraculous catch of fish (Lk. 5:1-11), one can see how in the background fish is being supplied on the quays. Its location reminds of the Antwerp Wharf with the fish market in front of the Steen. On the right panel another pair of brother-fishermen is shown at The calling of James the Greater and John (Mth. 4:21-22, Mk. 1:19-20). They leave their fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. Zebedee behind in the boat. Due to the adaptation to the new altar James in grisaille disappeared from one outer wing and Philip on the other was severely damaged.

In 1585 the soap boilers returned to their former chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

in the southern ambulatoryProcessional way around the chancel, to which choir chapels and radiating chapels, if any, give way., but because their financial capacity was limited they shared their altar with the guild of the schoolteachers. Is it a co-incidence or not that in those years the guild of the schoolteachers had their meetings in the adjacent chapterAll the canons attached to a cathedral or other important church, which is then called a collegiate church. In religious orders, this is also the meeting of the religious, in a chapter house, with participants having ‘a voice in the chapter’. sacristyThe room where the priest(s), the prayer leader(s) and the altar server(s) and/or acolyte(s) prepare and change clothes for Mass. under the guidance of the scholaster, the canonSomeone who, together with other canons, is attached to a cathedral or collegiate church and whose main task is to ensure choral prayer. responsible for education? According to the customs of those days the meeting about the usage of the altar took place in an inn, in this case ‘t Rood Leeuwken in Kammenstraat. In 1587, only two years after the restoration of Catholic worship, they were the first corporation to gloriously re-establish their guild altar with a retable in the cathedral.

The central panel:

The finding of Jesus in the Temple

(Lc. 2:41-50)

The Temple of Jerusalem looks very much like a – in those days – modern Renaissance church, with in the background the sanctuary which represents the Holy of Holies. In it there is no altar, but the menorah or seven branched candleholder in front of the Ark of the Covenant. Mary and behind her Joseph, who have lost their twelve year old child, find him back here, sitting in the midst of the teachers (v. 46). Mary, who can be identified by the blue cloak and the aureole, dismayed, with her right hand open, asks Him: Son, why have You treated us this way? Behold, Your father and I have been anxiously looking for You. But Jesus answers: Did you not know that I had to be in My Father’s house? (v.48-49) and with His stretched right forefinger he points upward and at the same time at the Temple’s sanctuary.

The Jewish scribes consult the Old TestamentPart of the Bible with texts from before the birth of Jesus. scriptures to answer Jesus’s questions (v. 46) or are amazed at His understanding and His answers (v. 47). One of them is looking at a prophesy of Isaiah (7:14b) that is connected to Jesus: Behold, a virgin will be with child and bear a son, and she will call His name Immanuel. The Antwerp schoolteachers could identify with the Jewish scribes, who, eager to learn, have gathered around Jesus. After all: a true teacher remains a pupil … certainly of this ‘One (…) Teacher’ (Mth. 23:8). This was an occasion for the governors of the guild to have some of their members portrayed among the bystanders – no lack of vanity. The tempting opinion to recognize portraits of Luther (with spectacles and a round face) and Calvin (with an elongated face and a beard) in the two scribes bottom left, have been widespread – by a guidebook – at least since the second half of the 18th century. Because the scribes’ function is to be professional role models for the (Catholic) Antwerp teachers, it is out of the question that the two most important challengers of the Catholic Church would be part of them. The hooknose, which is to represent a ‘Jewish nose’, of the bearded scribe, moreover, does not correspond at all with Calvin’s typical nose, which was as straight as an arrow and which by then was very known all over Europe thanks to prints.

The left wing:

Ambrose baptizes Augustine

The schoolmasters’ guild honoured Saint Ambrose of Milan as their patron saint. Also the schoolchildren celebrated his saint’s day on 7th December. The holy bishop’s mitreThe ceremonial headgear of bishops and abbots. The front and back are identical pentagons pointing upwards. has been decorated with a beehive, the symbol of ‘honey tongued’ eloquence. This helped Ambrose to convince many to become a Christian, including Augustine, who he himself was a teacher. On EasterThe feast that celebrates the resurrection of Jesus on the 3rd day after his death on the cross. This means that Jesus lives on despite his death. This feast is celebrated on the 1st Sunday after the 1st full moon of spring. Saturday Night 387 Ambrose baptized him. At the level of his heart on his christening gown Saint Augustine is wearing a cockade with two crossed arrows through a heart, his attribute, which goes back to his famous quote: With the arrows of your charity you had pierced our hearts, and we bore your words within us like a sword penetrating us to the core (Confessions IX, 2:3). Monica, who has devoted herself very hard to the conversion of her son Augustine for years, is watching. No doubt the female teachers, who were half of the 80 teachers in Antwerp in 1587, felt affinity with Saint Monica and could identify with her. After all her home tuition was crowned with her famous son’s profession to the Church. Scholaster Reynier van Brakel shows suitable respect in kneeling down in the foreground.

The right wing:

The prophet Elisha and the miracle of the widow’s oil

Oil is the base component of soap. So, the theme of an oil miracle was extremely suitable for the soap boilers, who paid for this panel. The prophet Elisha follows the footsteps of his famous master Eliah and also follows him with an oil miracle of his own. The bald man, clad in the red prophet’s cloak of his master, helps a widow, the mother of two sons, get out of debt by seeing to it that she can fill a great number of (borrowed) jars with a little oil left in a jug (2 Kings 4:1-7). As a prefiguration of the crucifix in a Catholic living room, on the mantelpiece there is a painting with Moses and the brass snake (Num. 21:9) (cp. Predella of the high altar)

On the outer wings the evangelists are around a table that continues across the two panels. In the beginning of the 19th century the wings returned from the Antwerp École Centrale.

For their chapel in the ambulatory the cabinetmakers commissioned a fashionable altarpiece by the renowned painter Hendrik van Balen in ca. 1620 and he finished it two years later. True to tradition the patron saints of the Antwerp cabinetmakers, the two saints John, are in grisaille on the outer wings. By the working of shadows they are nearly transformed into statues in niches. Inside attention is only paid to John the Baptist: the three panels concisely summarize the story of his life in as many scenes, from left to right.

The left wing:

John the Baptist’s birth,

or more precisely, his first bath.

Mary came to visit her elder, pregnant cousin Elizabeth ‘in her sixth month’ (Lk. 1:36) to stay ‘with her about three months’ (Lk. 1:56) and so she could assist her in the period of the delivery. In art this excerpt will be used to develop the scene of John’s first bath, administered by Mary. Here too she can be identified by her traditionally blue and red garments, which the preparatory pen drawing (Kupferstichkabinett of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) does not make us presume yet. On the left, hardly to be seen with the bare eye, Elizabeth is still lying in the childbed, all eyes on her baby. The angels allude to the divine mission of the child, as was foresaid to his father Zachariah (Lk. 1:13-17) and confirmed by Jesus: He who will prepare Jesus’s way before Him, no one greater among those born of women (Lk. 7:27-28). The angels’ joy, singing and music suggest that ‘many will rejoice at his birth’ (Lk. 1:14). Because he was already sanctified from the womb, John is, together with our Lady, the only saint whose day of birth is celebrated, on 24th June.

The central panel:

The preaching of John the Baptist

(Lk. 3:1-17)

John, who is living in the desert, preaches to a varied crowd (v.7) in the district around the Jordan (vv. 2-3). We can understand that traditionally this preaching was situated in a shadowy oasis, and, as is the case here as well, on a small elevation. With his forefinger pointing to Heaven the extravagant prophet, ‘in a garment of camel’s hair’, emphasizes his words about the wrath to come (v. 7). On the questions about what to do so as not to be thrown into the fire and to bear good fruit (v.9), he gives suitable answers for each category. The rich, who can be recognized by their costly costumes, are to share their affluence with those who have nothing (vv. 10-11). For the publicans, who cannot be recognized due to lack of uniform, the message is to be professionally correct and not to cheat (vv. 12-13). The Roman and contemporary soldiers are urged not to extort (v. 14). The bearded man with the Hebrew word ‘JHWH’ on his headdress and the person he is talking to, probably stand for the Pharisees and the lawyers, who do not let themselves be baptized (Lk. 7:30).

By lightening the warm, varied colours of their garments, van Balen leads the spectator’s attention first to the woman who is sitting down with her children in the bottom right corner. This outsider at first sight, is more than a mere repoussoir for the scene. By pointing to John she does not only direct her playing children’s attention, but also the spectators’ to ‘Jesus’s trailblazer’.

The right wing:

Saint John the Baptist reprimands King Herod because of the adulterous marriage with his sister in law Herodias.

With an accusing forefinger the man of God admonishes: It is not lawful for you to have your brother’s wife. (Mk. 6:18). Herod is prepared to listen and looks up at John, but at the same time he is tensed and recoils. This shows his inner struggle: when he heard him, he was very perplexed; but he used to enjoy listening to him (Mk. 6:20).

This scene also announces the beginning of the end of John’s life. In the background is Herodias, who had a grudge against him and wanted to put him to death (Mk. 6:19) and who is whispering a way to get rid of this critical prophet into her daughter Salome’s ear, which alludes to John’s decapitation after Salome’s dance (Mk. 6:21-28).

The wings were always in the cathedral but since 2008 they have been reunited with the central panel, thanks to a long term loan of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, formerly the École Centrale, for which it was originally requisitioned.

‘Wine taverners’ were wine merchants who also served wine in their own inns. This guild provided the city with one of the most important excise revenues. When in 1596 they no longer shared their altar with the coopers they contacted one of the most important painters, Maarten de Vos, to commission an altarpiece for their new place of worship in the easternmost chapel of the ambulatory. To make a link between Jesus’s gospelOne of the four books of the Bible that focus on Jesus’s actions and sayings, his death and resurrection. The four evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. ‘Gospel’ is the Old English translation of the Greek evangeleon, which literally means ‘Good News’. This term refers to the core message of these books. and their professional activities the choice for the popular Biblical story of ‘the wedding at Cana’ (John 2:1-11) was obvious. What happened to the painting during the French Revolutionary Rule is unknown. Anyway it popped up in the church again in the 19th century and ended up in the southern transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right..

Among the wedding guests, seated at a long table in a contemporary sumptuous interior, there is the appropriate festive atmosphere, to which lustre is added by three lute-players and a boy singer on a wooden singers’ balcony in the background (such as one that has been preserved in Antwerp, in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwehuis, alias Hotel Delbeke, in Keizerstraat).

The scene seems to show a snapshot, but the attentive Bible expert notices that nearly all the phases of the Biblical story have been staged here. According to the story’s chronology they have to be read from left to right and making a circular movement anticlockwise they finally end up left again.

After Mary (M), on the left, who can be recognized by the white and blue clothes, has noticed that the wine threatens to run short, she instructs one of ‘the servants’ (S1) with her right forefinger stuck up: Whatever He says to you, do it (v. 5). For Counter Reformation this was an outstanding anecdote to illustrate Mary’s mediating role.

Jezus (✛), who is nearly in the centre of the composition, attracts even more the attention with his brightly red cloak. He indicates the pitchers of the Jewish ritual cleansing, which are all six spread along nearly the entire width of the foreground. He instructs a servant to fill them again. They filled them up to the brim (v. 7).

Then we see the reactions of the guests, about which the Bible however does not say anything. Further to the right in the background a waiter (S3) serves some miraculous wine to a woman: white Rhenish or Moselle, which was so popular in the Antwerp region. The other guests animatedly discuss the new, better wine. Also the rich bride (1), in white satin and with a golden crown, is offered a tazza with the miraculous wine by her mother (2), encouraged by her father (3). Indeed, in conformity with the then wedding traditions the bridegroom is not at table yet with his bride, as long as the marriage has not been consummated. The bride is flanked by her parents in front of a tapestry of honour, while above their heads three crowns have been hung. Not to be seen is how the headwaiter, who did not know where the wine came from, calls the bridegroom to account for the inverse course of events, in which the better wine is only served at the end of the feast (vv. 9-10). The man with the headdress and the red clothes (4), who has pushed himself in between the table guests on the left, is the head waiter, who has learned the full facts of the case from ‘the servants who knew’ (v.9). He points out Jesus as the one who committed this inappropriate, but miraculous act. And so we have come full circle.

On the pitcher bottom right the abduction of Proserpina (Greek: Persephone) by Pluto (Hades) to the underworld alludes to the marriage still having to be consummated, after which the bridal couple will be allowed to sit together at table on the second day of the wedding feast. In spite of all the aspirations of the wine taverners, the Biblical meaning of this miraculous story however does not focus on the consumption of wine, but on God’s overwhelming love, which wants to fulfil every heart. The individual portraits, presumably of governors of the guild, indicate that these gentlemen are longing to take part in this wedding feast with God in Heaven.

It is not clear whether there used to be wings. The altar was crowned with a statue of Saint Martin. This popular saint became the patron of the guild because the winegrowers tasted the young wine during a festive meal at the beginning of the slaughtering season, on 11th November, his day of feast. His image on a keystone in the most central southern aisle indicates the place of the former Saint Martin’s altar.

There is not a single trace left of the vault paintings to indicate the original location of the former coopers’ altar in the central nave, against the second southern pillar (from the crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept].). The two altar pieces with the martyr’s death of the patron saint have been preserved all right, but incidentally in Saint Paul’s Church. The first one, Saint Matthias’s martyr’s death by Hendrik Herregouts, from 1680-1681, was commissioned by the coopers’ guild. The second one, The stoning of Saint Matthias, was made only three years later by Willem de Rijck and given to the coopers by him. As both paintings are on canvas, the coopers could easily alternate them on their altar. After the high altar of the Jesuits (1621, Saint Charles Borromeo’s Church) and this of the Dominicans (1670, Saint Paul’s Church), there was also some variation on a guild’s altar in the cathedral.

The three white marble predella reliefs of the portico altar that Artus II Quellinus and Ludovicus Willemsens made for the coopers in 1677-1678, were re-used as predella parts in the rear side of the high altar, which Jan Blom made in 1822-1824. Tubs, barrels and casks give little rise to Biblical spiritual reasoning, but: seek and you will find. The receiver refers to the wine that is kept in it. Hence the theme of the ‘mystical winepress’ – with Christ symbolized by his five wounds – which refers to the (pressed grapes of the) wine, which in the Eucharist stands for Jesus’s bloody sacrifice. On the side panels winged putti carry grapes and corn.

Each altar against a pillar in the central nave had an altar enclosureA wooden or marble construction around an altar that demarcates the space reserved for the priest. In Antwerp, altar enclosures can still be seen in Saint Andrew’s Church.. Initially these were made of wood with brass balusters, but in the Baroque they were of fashionable marble. Of the twelve altar enclosures not one is left. Thanks to the fact that the Province of Antwerp has bought three of the six opened out panels of the coopers’ Baroque altar enclosure they are back in the cathedral. They were dated ‘1683’ and signed ‘G.K.’: Guillielmus (= Willem) Kerricx. They show plastically how and with which tools barrels were manufactured: saw, mattock, drill, plane, file. On the other hand the cup, tap, screw top and wine funnel indicate how first of all they were used for wine. Their bozetti have been preserved in Brussels, Belgian Royal Museum of Fine Arts. This varied collection of tools, together with the wine press, were also represented in the Baroque, wooden bannister of the wine taverners’ guild house in Veemarkt (now they are part of the collection of the MAS).

For the stocking knitters the legendary Mother Anne was a model of domestic zeal because of her extensive family. The Gothic key stone of Virgin and Child with Saint Anne near the north west mother pillar indicates the stand that this guild had uninterruptedly since its foundation in ca. 1487. For their Baroque altar Peter II Verbrugghen made the white marble predella relief The birth of Mary (second half 17th century, now in the Church Wardens’ Room). While Mother Anne is still resting in the childbed, and the midwife is leaving the room, two nurses take care of the baby: they will wash her and swaddle her. Near the hearth-fire the wicker cradle is waiting, which explains the old name of this altar: ‘Onze-Lieve-Vrouw in kinderbedde’ [Our Lady in child’s bed].

The white stone statue of Saint Gummarus, which was originally polychromely painted and had a staff in its hand (first half 17th century), crowned the altar of the wood breakers, against a pillar the northernmost aisle.

Of the six altars that belonged to city guards only the two white marble statues of two Old Testament warriors are left on the spot: Gideon, with a broken jar and a sceptre (Hubert van den Eynde) and Joshua (the lance is missing, Artus II Quellinus). They functioned as models for the fencers at their Saint Michael’s altar (after 1650), which stood against the southern mother pillar of the central nave. Now they are in the back of the nave, against buttresses of the towers.

- Our Lady’s Cathedral

- History & Description

- Preface

- Introduction

- Historical context

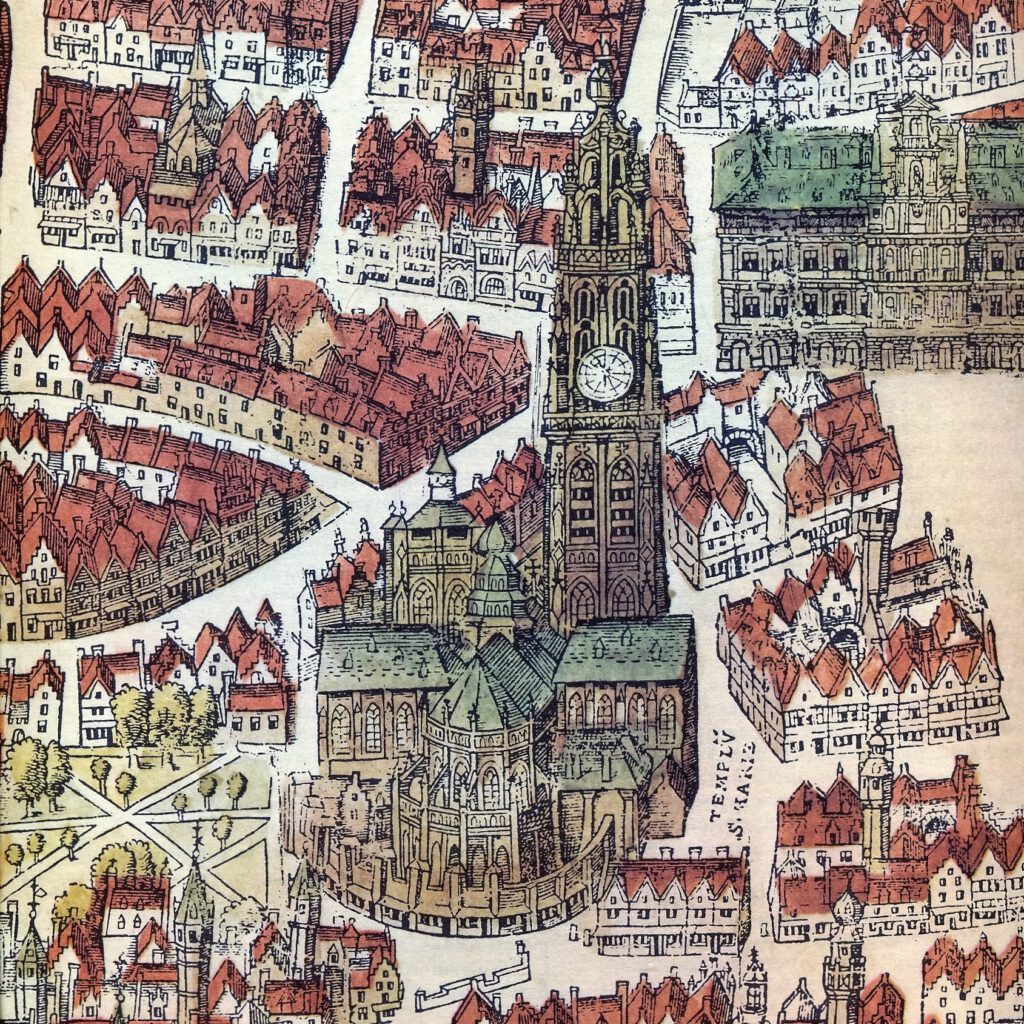

- A centuries-long building history

- A cathedral never stands alone

- Our Lady’s spire

- The main portal

- Spatial effect

- Mary’s Assumption (C.Schut)

- Erection of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- Descent of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- The Resurrection (PP.Rubens)

- Mary’s Assumption (PP.Rubens)

- The high altar

- The collegial choir

- The bishop’s church

- The parish church

- The pulpit

- The confessionals

- Caring for the poor

- The Venerable chapel

- Mary’s chapel

- Corporations and guilds

- The ambulatory

- Funeral monuments

- Praise the Lord!

- Pull all stops: the organs

- Cross-bearer (J.Fabre)

- Bibliography