The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

The Raising of the Cross (Peter Paul Rubens)

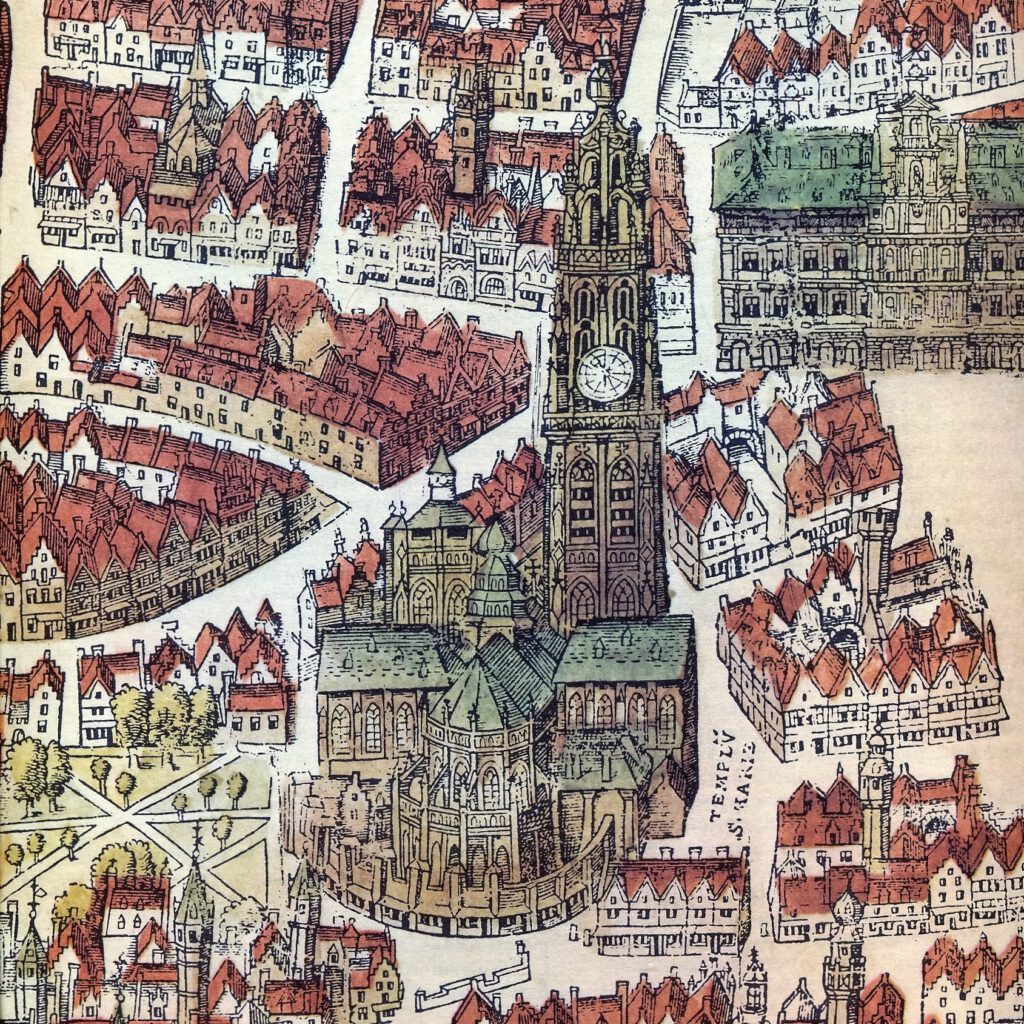

Our Lady’s CathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is. is especially renowned for its paintings by Rubens: masterworks of Baroque art. Their coloration and rendering of light succeeded in fascinating many an artist, including Vincent Van Gogh, during their visit. Now two of the four paintings are each other’s counterparts in the transepts. The Descent from the Cross is still very near to its original position in the Southern transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right.. The Raising of the Cross came from SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Walburga’s Church, which was doomed to be demolished, and so in 1816 was the ideal solution for the empty Northern transept. These two impressive altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine. pieces were still conceived as triptychs with about the same, large, dimensions and have a central panel with a similar diagonal composition. Their themes are also contiguous: the one shows the moment before, and the other one the moment exactly after Jesus’s death on the cross. When you add the neo-Gothic triumphal crossLarge crucifix hanging in the first arch of the choir or chancel. In churches with a rood screen, the triumphal cross usually stands on this. (1845) in the crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept]., between both triptychs, you get a perfect staging in three acts of Jesus’s crucifixion.

The first official commission Rubens received, after the Twelve Year’s Truce had been concluded, in 1609, came from the committee of church wardens of Saint Walburga’s church and concerned a monumental high altar. But the ‘most important initiator and promoter’ – according to Rubens’s posthumous message of thanks on an etching after the painting – was the wealthy spice trader Cornelis van der Geest. This great art-lover and Maecenas, who could afford one of the most important art collections in Antwerp, an ‘art cabinet’ including two works by Rubens, eagerly wanted his own parish church to make use of Rubens’s talent to the advantage of all churchgoers.

Because the choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. was long and about three metres (10 ft.) above street level, there was a large distance between the high altar and the churchgoers in the naveThe rear part of the church which is reserved for the congregation. The nave extends to the transept.. Due to this the didactic intention of an altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. – a concern proper to Counter Reformation – might have been difficult to realize. This is why the triptych became exceptionally large: 4.6 m (15 ft.) tall and when opened completely 6.4 m (21 ft.) wide. Moreover the width was completely used for one tableau. Thus – at least in the Low Countries – two new records were set: in terms of dimensions and in terms of the original composition. To have a good view of the complete scene, spread over three panels, Rubens’s first workshop, at his parents in law’s in Kloosterstraat, was too small. This is why it was decided to execute the monumental work on the spot, in the vast choir. A stretched ship’s sail had to avoid the painter being disturbed by inquisitive visitors during his work.

Initially the triptych was closed for the greater part of the year so that only the exterior wings, reserved for the four patron saints of the church, got the full attention. In the background – but more closely flanking God the FatherPriest who is a member of a religious order., who sat enthroned in the original altar crowning – are the most important ones: abbessThe woman who has been chosen by the abbey community of which she is a member to lead that community for a fixed period. Walburga and the first proclaimer of the Christian faith in Antwerp, bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’. Eligius. In the front are his successor, bishop Amandus, and the popular Catherine of Alexandria. Loyal to liturgical tradition the exterior panels are in austere brown ochre, but for Rubens this was not an obstacle to transform them into lively characters with a few skimpy patches of colour.

In fact a painting like The Raising of the Cross is not just meant to be looked at. This may sound strange, unless, as people were in Counter Reformation times, you are familiar with the method of meditation introduced by Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits. He found it most important to approach the (message of the) gospelOne of the four books of the Bible that focus on Jesus’s actions and sayings, his death and resurrection. The four evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. ‘Gospel’ is the Old English translation of the Greek evangeleon, which literally means ‘Good News’. This term refers to the core message of these books. through the senses and in this way he greatly influenced Baroque culture. He wanted you to crawl into the story of the gospel in order to experience everything as if you were part of it yourself. To this end Rubens applied a number of tricks offered to him by the possibilities of painting, but exactly the same ones as those you can see in the cinema nowadays. As on the silver screen the story is presented more than life size, which enables you to identify easily with the characters. Such large format met the didactic purpose of Counter Reformation religious art.

By using a worm’s eye view the artist wants the viewer to be impressed more by the figures he is looking up at. Rubens leads the eye of the viewer along the diagonal line of the cross: from below on Mount Calvary up to Jesus’s face. No doubt this upward effect must have been a lot stronger in Saint Walburga’s church since the altar in the sanctuary was on a platform of no less than 19 steps.

For the composition Rubens was inspired by Saint Andrew’s martyrdom, which his master Otto van Veen painted for the Antwerp Saint Andrew’s church in 1597-1599. But Rubens made it more dynamic by using the diagonal, this typically Baroque line of force, to suggest the upward movement. Besides Rubens has geared the composition of each interior wing to this of the central panel. It is good to be aware of the fact that the wings of the triptych were spread fully for 180°. At both sides of the tumultuous exhibition of force up and downward, seemingly criss-cross, compositional lines purposively lead all the attention to the crucified Jesus. The continuous background of the rock with plants and of the clouds emphasizes the thematic unity of the three panels.

Following Caravaggio Rubens painted figures who look outside the painting and search eye-contact. By catching your eye it is as if the woman in the green dress, in the centre near the extreme rim of the left wing, wants to keep your attention with the representation.

Once the spectator has become part of the space of the tragedy, he is invited to contemplate the scene well: also to hear and to feel what is happening. For such a sensory exploration no better artist than Rubens could have been chosen. With a most true-to-life rendering he increases the spectator’s commitment. How juicy are the leaves on top! How soft is the hair of the horse in the right wing: to be caressed. Mark the varied reflections of light in every curve of the Roman soldier’s cuirass: heavy metal. Notice how the three primary colours red, yellow and blue have been spread disparately. The colours have been worked out completely into a pallet of darker to lighter shades, depending on the painted play of light. This realistic tangibility of the dramatis personae of flesh and blood, going together with psychological realism, is also to be felt in the combined effort of the executioners, who push, heave, haul and pull the cross to force it upward. All this contrasts firmly with the dazed faithful followers, who can only pull back weeping or can only offer their loving closeness silently and resignedly.

The athletic figure of Jesus, with His crown of thorns, has only just been nailed to the cross. The blood is still gushing warm from the wounds. On the cross there is the sign with the reason of the execution: ‘Jesus of Nazareth, king of the Jews’. It was written in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek (John 19:20). To evoke the vivid impression that the notice is moved by the wind, the last Latin word ‘Iudeorum’ cannot be read: a gimmick Rubens could permit since everybody who had attended school in those days, knew Latin and this sign. Abandoned by the leaders of his people, by the crowd that has cheered Him quite recently, and by almost all his (cowardly) disciples Jesus undergoes His crucifixion. More than His tortured body it is Jesus’s look in His eyes that speaks and evokes the Seven Words of the Cross ranging from total despair – My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? (Mt. 27:46) – to faithful submission: Father, into your hands I commend my spirit (Lk. 23:46). Jesus only has eyes for His Heavenly Father, who originally figured on a separate panel in the centre of the altar’s crowning, illustrating Jesus’s words: When you lift up the Son of Man, then you will realize that … the One who sent me is with me (John. 8:28-29).

The empathy with this human tragedy should help you to distinguish between good and evil, so that finally you can make the right choice: ‘Which role would I want to be mine?’

Would you like to collaborate with the power of evil in the right wing, which is not by coincidence symbolically left of Jesus? With the Roman officer on horseback, who with his sceptre commands to execute innocent Jesus? The Roman banner ‘(SP)QR’ (Senatus Populusque Romanus: The senate and the people of Rome) confirms his authority. On this wing are the two real criminals, murdering robbers, who are crucified as non-Roman citizens: one is being nailed to the cross, the other one is led to it as a prisoner.

Or do you rather identify with the indifference of the executioners in the central panel? They might not have an evil disposition, but they do listen to evil, out of obedience or pursuit of profit or social pressures. The hound, a spaniel, underlines the threat coming from this bunch of bullies and refers to traditional iconography of the Passion, which goes back to the psalm of the Suffering Servant: Dogs surround me, a pack of villains encircles me; they pierce my hands and my feet (Ps. 22:16). The only one whose eyes can really be seen is the Roman soldier in armour. His protruding eyes seem to wonder who this Crucified Man might be and betray the internal conflict between sensing what is good, and executing evil.

Or would you not rather offer your affectionate nearness to the bitter end, at Jesus’s right hand side – on the left panel – as a real friend, like John, or the weeping mother Mary, who participate in His suffering motionlessly? It is not by chance that she is at eye level with her Son. Her faded, deathly pale complexion is even duller than Jesus’s, as if Rubens wanted to make clear that the mental torture is even worse than the physical one. Amidst the other holy women Mary Magdalen modestly bows her head towards her Master. A child crawls away with fear near the dumbfounded old woman. The mother in front shrinks back in amazement and she keeps her crying baby against her, who, although not realizing what is going on, forgets to feed.

Finally there is also a part for those who out of mere self-preservation want to flee, as the other ten apostles did.

In the right wing, top left the moon slides in front of the sun and it is not by accident that it does so in the same upward movement as Jesus’s cross does: chronologically from left to right. With this total eclipse that is at hand (Lk. 23:44-45a) it is clear that Jesus, ‘the Light of the world’, will not be among mankind for long. Thus were Jesus’s own words in the Gospel that was then read on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (14 September, a prescribed feast-day until the end of the 18th century): The light will be among you only a little while… (John 12:35).

But darkness never gets the last word. Both on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross and on Palm SundayThe Sunday before Easter. On this day, the joyful entry of Jesus into Jerusalem is commemorated. During the liturgical celebrations of Palm Sunday, the Passion of Jesus is read in its entirety. Jesus’s humiliation and His glorification belong together, which is shown in the fact that the same EpistleIn Mass, the Bible reading(s) preceding the gospel reading. According to the lectionary, there are always three readings on Sundays: one from the Old Testament, one from the non-gospel texts of the New Testament and one from a gospel. The first two readings are often called the epistle but strictly this word refers only to the letters of St Paul and other apostles. is read on both feasts: Philippians 2:5-11. This is emphasized even more by the ambiguous usage of Christ’s ‘exaltation’. At first sight only Jesus’s way of dying on a raised cross is meant, but in verses 8 and 9 of the Epistle univocal reference is made to His glorification with God in Heaven. Moreover this is underlined in the next verse, which invites people to kneel down, and which in the Tridentine massThe liturgical celebration in which the Eucharist is central. It consists of two main parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The main parts of the Liturgy of the Word are the prayers for mercy, the Bible readings, and the homily. The Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the offertory, whereby bread and wine are placed on the altar. This is followed by the Eucharistic Prayer, during which the praise of God is sung, and the consecration takes place. Fixed elements are also the praying of the Our Father and a wish for peace, and so one can symbolically sit down at the table with Jesus during Communion. Mass ends with a mission (the Latin missa, from which ‘Mass’ has been derived): the instruction to go out into the world in the same spirit. was expressed ritually in a kneeling gesture by all believers. On Palm Sunday this Bible text is the link between the initial gospel reading about Jesus’s glorious entry into Jerusalem and the story of the Passion. The triumphant procession of entry accompanied by waving palms can also be seen as a prefiguration of Jesus’s entry in Heaven. According to the Tridentine rite in Rubens’s day people knelt down twice during the reading of the lessons: at the moment of Jesus’s death and at the verse of the Epistle about His exaltation with God. Probably after having consulted the trained academic parish priestA priest in charge of a parish. of Saint Walburga’s parish, Franciscus Hovius, Rubens took this liturgical custom as a starting point to work out ‘the Exaltation of Christ’ even further into its second sublime meaning, but this time on a higher level and in a dynamic Baroque way. On the original crowning of the altar two more than life size angels used to wave palms triumphantly, in a staggering trompe-l’oeil and on carved out panels: not so much to honour God the Father, who was depicted between them, but rather to glorify Jesus’s sacrifice of His life, underneath, as a unique victory of God’s love. Simultaneously Jesus was thus welcomed in Heaven. This concept was totally modern then and constituted the step towards the Baroque portico altar with a double iconographic level.

In 1734 however, this original iconographic coherence was undone by Willem Ignatius Kerricx, who started replacing the early Baroque altar by a high Baroque marble portico altar, preserving only the central panel. The wings were put against the choir walls and the other six panels were sold. In Jesus’s Raising of the Cross an even deeper spiritual meaning lies hidden. The worshippers, who followed the Eucharist from a distance, identified the Crucified Christ with the one whose sacrifice of love they experienced again during consecrationIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words.. But when the priestIn the Roman Catholic Church, the priest is an unmarried man ordained as a priest by the bishop, which gives him the right to administer the six other sacraments: baptism, confirmation, confession, Eucharist, marriage, and the anointing of the sick. was celebrating mass at the altar below and during consecration held up the sacred hostA portion of bread made of unleavened wheat flour that, according to Roman Catholic belief, becomes the body of Christ during the Eucharist., looking up at it he saw the meaning of it projected life size in the same clear colour: ‘the Body of Christ’. Christ’s selflessness – His willingness to give Himself completely – was once again repeated symbolically in the EucharisticThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live. motif of the (gilded) pelican that was originally on top of the altar.

In 1794 The Raising of the Cross was taken to Paris by boat and cart, together with some seventy masterpieces of the Antwerp school of painting. For the French this was war booty and in the national museum of the Louvre it illustrated the fame of Pieter Paul Rubens. Once the French had definitively been beaten at Waterloo in 1815, the triptych returned to Antwerp and this highlight of Baroque painting and of Catholic faith could luckily be placed in a church again, where it belongs, although no longer as an altarpiece.

Among the admirers of Rubens’s paintings there are a lot of Japanese. This is not a coincidence because in every Japanese school A Dog of Flanders is taught, a typically 19th century romantic story by Ouida, whose real name was Marie-Louise de la Ramée. It tells about the poor orphan boy Nello, from a neighbouring village, who tries to earn some money delivering milk in Antwerp with his dogcart. Moreover the boy loses his job because he was falsely accused. The only friendship that was left was this of his loyal dog Patrasche. His ultimate dream: to be able to admire the famous paintings by Rubens in Our Lady’s Cathedral, because these were then mostly covered with curtains and could only be looked at by those who paid for it. During ChristmasThe feast commemorating the birth of Jesus. It is always celebrated on December 25th. Night he is fortunate to find the church doors open, and enters it completely exhausted. With an ultimate effort he is able to remove the curtains from both triptychs and to praise their beauty thanks to the white shade of the moon. When darkness covers Christ’s face again Nello, holding his dog in his arms, says: ‘We shall see His face—there, and He will not part us; He will have mercy.’ The next morning both friends are found, frozen on the cold church floor. Meanwhile ‘the fresh rays of the sunrise touched the thorn-crowned head of the Christ’ – i.e. on The Raising of the Cross.

- Our Lady’s Cathedral

- History & Description

- Preface

- Introduction

- Historical context

- A centuries-long building history

- A cathedral never stands alone

- Our Lady’s spire

- The main portal

- Spatial effect

- Mary’s Assumption (C.Schut)

- Erection of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- Descent of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- The Resurrection (PP.Rubens)

- Mary’s Assumption (PP.Rubens)

- The high altar

- The collegial choir

- The bishop’s church

- The parish church

- The pulpit

- The confessionals

- Caring for the poor

- The Venerable chapel

- Mary’s chapel

- Corporations and guilds

- The ambulatory

- Funeral monuments

- Praise the Lord!

- Pull all stops: the organs

- Cross-bearer (J.Fabre)

- Bibliography