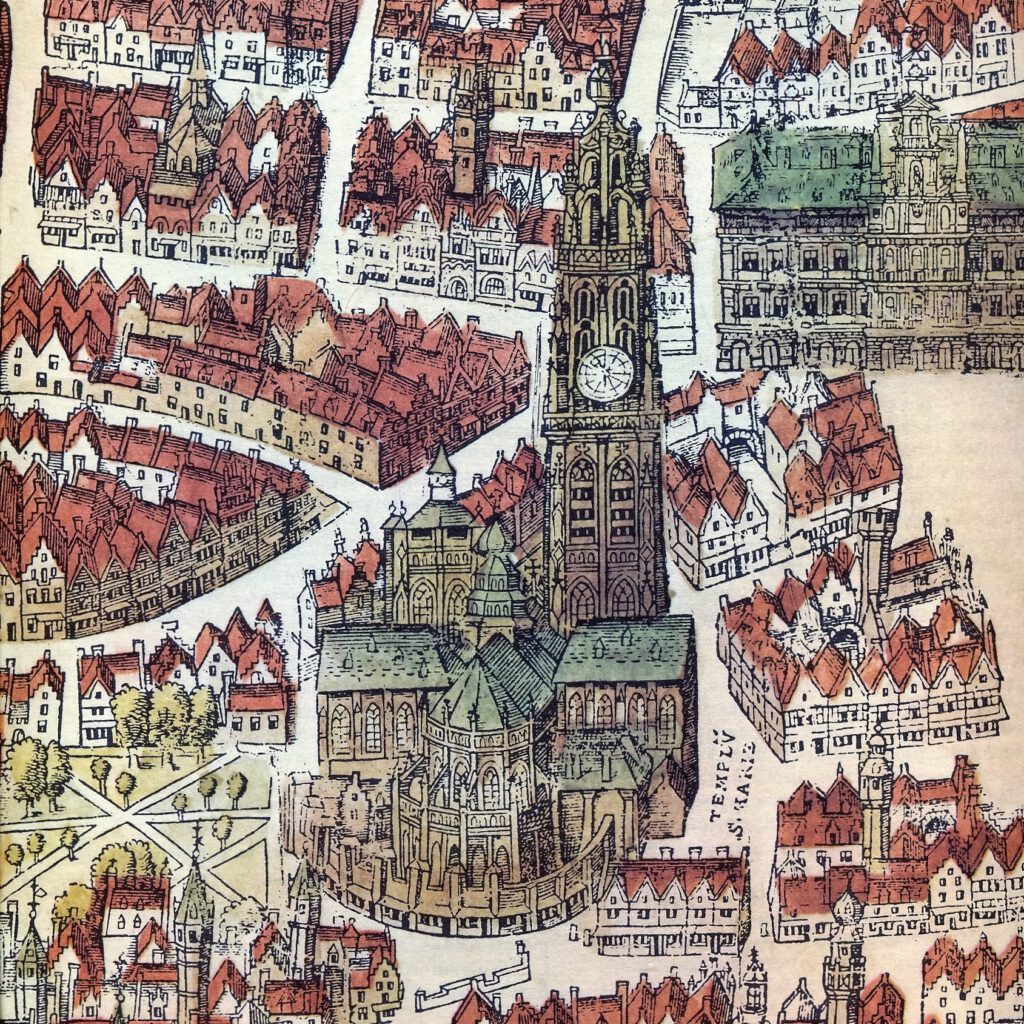

The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

The Descent from the Cross (Peter Paul Rubens)

The triptych The Descent from the Cross is undisputedly a splendid masterpiece by Rubens, which is rightly considered among the most famous paintings of Flemish heritage and the entire Baroque. On the statue in Groenplaats (Willem Geefs, 1840) that honours Antwerp’s most renowned citizen, Pieter Paul Rubens not surprisingly has a sheet of paper lying at his feet, representing a swift sketch of his most famous masterpiece.

In the campaign of restoring the altars after 1585 the archebusiers, a civic guard using fire weapons, quickly built up their altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine. again, but contrary to nearly all other citizen militias it took quite long before a triptych was commissioned: until the beginning of the Twelve Years’ Truce. In order to pay the cost they could use the money with which some new guild members, so-called ‘wepelaars’, bought off their armed service. In 1611, the year the work was put to tender, their captain was Nicolaas Rockox, Rubens’s ‘vriendt ende patroon’ (friend and patron) and also exterior mayor. This humanist intellectual and pious Catholic was married but childless and spent his enormous fortune mainly on poor relief and patronage of the arts. His house in Keizerstraat now is one of the most beautiful historic museums in the city. Very soon he discovered Rubens’s talent after the latter’s return from Italy. Just like three other civic guards with a large number of members, which could amount to 200 or even 300, the guild of the archebusiers had their altar in the vast transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right. of the cathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is., which also accounts for the dimensions of the triptych: 4.2 m (14 ft.) high, with a width of 3.1 m (10 ft.) for the central panel and 1.5 m (5 ft.) for each of the two wings. The altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. by Rubens is still in the Southern transept, at a few yards of its original position. Unlike The Raising of the Cross Rubens did execute this commission in his workshop in Kloosterstraat, because this time it concerned three panels with different scenes. One year later, 12 September 1612, probably not by chance just before the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (14 September) the central panel was put in position. Two years later the two wings came to ‘close’ the commission and the completed triptych was consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words..

Traditionally the long, narrow exterior wings of altar triptychs are reserved for the patron saints, usually as static imitations of statues. The patron saintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. of the archebusiers was Saint Christopher, but here he acts as the vivid main character of his legend. Reprobus, the giant from the medieval legend, liked to throw his weight about by entering the service of the king, for whom everybody stood in awe. But one day Reprobus found out that this mighty monarch was afraid: of the devil. This is why he immediately offered his services to the devil, presuming that this was really the most powerful one. But he was wrong. Also the devil felt fear, namely for Christ, the Son of the one, almighty God. So Reprobus went in search of Christ. After a long quest Reprobus met a hermitA person who lives alone and isolated from the world in order to live a sober and pious life. The home of a hermit is called “hermitage”. by a river, who taught him the Christian faith and assured him that Christ would certainly appreciate him if Reprobus helped people cross the dangerous river. The giant put travellers on his strong shoulders and carried them across the river – free of charge. One evening a small boy came to him. Reprobus put him on his shoulders, but after a while the little child became so heavy that Reprobus nearly lost his balance. Only with all his strength he succeeded in carrying the boy to the other bank. Curious about the reason for the boy’s extraordinary weight, he was given as an explanation: ‘I am Christ, who has carried away the sins of the world’. Reprobus had understood: not ‘to throw one’s weight about’ is the message, you can only meet God when you are prepared to help other people carry their burdens. Reprobus had himself baptized by the name of ‘Christopher’, from the Latin ‘Christophorus’, which is ‘Christ bearer’. As a Christian version of the mythological Charon, Saint Christopher was regarded a protector on the last crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept]., the one to hereafter. According to medieval superstition those who looked at an image of Saint Christopher would be freed of an unforeseen death that day. This indicated that a person would not die without the last sacramentsThese sacraments are administered to someone who is in danger of dying through old age or illness. In this order, they are last confession, anointing of the sick and last communion., which in those days was understood as: not ready for the journey into eternity. As a consequence for men who, as the archebusiers, dealt with perilous gunpowder, Christopher became the patron for the ‘good death’. In the yearly procession the archebusiers hired stilt walkers to represent the gigantic saint, preceded by the hermit with the lantern: a popular attraction. No doubt the guild would have liked to see the popular saint in the central panel, but the Catholic Church demanded a purification of hagiolatry, as a reaction to the legitimate criticism of the Protestants. By the way, trendsetters of historical criticism on medieval hagiographies were the Antwerp Jesuits, whose research resulted in the monumental edition Acta Sanctorum (the real facts of the saints). The person of ‘Christopher’ was unmasked as merely legendary. Moreover the Counter Reformation demanded that in an opened altarpiece the sacrifice of love of Christ’s crucifixion should be prevalent. The solution consisted in drawing the attention thrice on the spiritual meaning of the name ‘Christopher’ illustrated by a story from the GospelOne of the four books of the Bible that focus on Jesus’s actions and sayings, his death and resurrection. The four evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. ‘Gospel’ is the Old English translation of the Greek evangeleon, which literally means ‘Good News’. This term refers to the core message of these books.: ‘to carry Christ’. The legend of Christopher was preserved however as a scene spread over the two exterior wings.

The central panel shows the tragic moment when Jesus is taken from the cross – which also offers its name to the entire triptych by Rubens. The choice for this title is obvious, because a hostA portion of bread made of unleavened wheat flour that, according to Roman Catholic belief, becomes the body of Christ during the Eucharist. of loyal followers is carrying Him. You sense the carefulness needed to let such a lifeless body diffidently down from such a high cross. The body sinks down, restrained by two men who are standing on ladders and hang over the crossbeam. One of them, the one leaning on the crossbeam top right, succeeds in holding the shroud skilfully between his teeth while with his one free hand he holds Jesus by his arm and slowly lets Him down. In this way he not only prevents Jesus’s body from tumbling down but he also helps to show Jesus’s body to the worshippers. His complex posture constitutes the start of a downward movement, which, from top left to bottom right, constitutes the diagonal composition line of this panel, and which is greatly built on Jesus’s lifeless body.

The sideways bent body, together with the loose right arm and the hanging head, make us feel the weight of Jesus’s robust but lifeless body. The pale colour of death contrasts strongly with the red of the blood that is dried or partly seeps down, especially at the level of the wound of the spear.

From some distance His head is respectfully flanked by the looks of two honourable Jews who were also among Jesus’s pupils. Joseph of Arimathea, a wealthy counsellor of the highest Jewish court of justice, the Sanhedrin, had been given permission by Pilate to take away Jesus’s body and to bury it. The helpful man, clad in dark blue, staggers on a sidelong ladder and succeeds in grabbing it with both his hands. In the moment before this he has taken the crown of thorns and pulled out the three nails. Also the Pharisee and Scribe Nicodemus, one of the most respectable Jews, was there to honour Jesus. He came to help. In spite of his stately gown he is also on a ladder. With one hand he keeps up Jesus’s right upper arm – to be seen by the beholder – with the other one he is holding the shroud.

Typified by the magnificent fiery red of his gown, Jesus’s beloved friend John, fully in the front and in the spotlight, is the most prominent of all faithful disciples. With a single foot balancing on the ladder, he braces himself to carry Jesus’s full weight.

Opposite, slightly more in the dark and – true to iconographic tradition – on the place of honour, which is the right hand side of Jesus, Mary is weeping. She is deathly pale. This mother’s grief is too inhuman to bear: her distorted face is too painful to observe. Broken-hearted she looks at her deceased Son, while in despair she stretches out her hands to touch Him.

The downward movement – and also the diagonal composition line – ends below in the kneeling Mary Magdalen and Mary of Clopas – a gesture full of respect and awe for their Master, while they look up at Him lovingly. Mary Magdalen holds Jesus’s foot with both her hands and lets it rest on her shoulder. This gesture can also be seen as an allusion to her sympathetic courtesy, when she washed Jesus’s feet in the house of Simon the Pharisee. Behind her Mary of Clopas nearly by stealth stretches out her hand so that she can hold a little corner of the shroud to be tangibly involved in this last farewell. Her naked forearm and the elbow of the man top right constitute an inclusion.

Rubens, who is known for his dramatic compositions full of fierce melodrama, shows tranquil emotions here: mark how bitter tears roll over the cheeks of Mary of Clopas. And because the two men on top really hang across the crossbeam – the man on the left risks nearly losing his balance – a three dimensional depth is created that strengthens the subdued power of the whole, which turns the heaviness of bearing into the core of The Descent from the Cross.

The precious relics of the crown of thorns and the three nails of the cross have been carefully laid in the plate in the corner bottom right. The blood in it comes from the sharp objects that deeply pierced the veins in Jesus’s body. And to prevent the written notice which was on the cross from flying away, a stone has been put on to it.

For the wings two moments of Jesus’s childhood were found in which he was not only physically carried, but in which also the meaning of his person is elucidated. On the left wing – according to the reading direction the first scene in chronological order – Mary, who is pregnant and carries Jesus in her womb, visits her old cousin Elizabeth, who herself is pregnant with John the Baptist. Elizabeth points at Mary’s lap, illustrating her words to Mary: (Most blessedUsed of a person who has been beatified. Beatification precedes canonisation and means likewise that the Church recognises that this deceased person has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. Like a saint, he/she may be venerated (not worshipped). Some beatified people are never canonised, usually because they have only a local significance. are you among women,) and blessed is the fruit of your womb. (Lk. 1:42) Behind both ladies, modestly in the background, the husbands also greet each other: Joseph and Zechariah (who is still dumb).

Obviously Jesus is carried at The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple on the right wing (Lk. 2::22-35). On the 40th day after his birth Jews presented their firstborn son to God. In the Temple there was very old and pious Simeon, who was expecting the coming of the Messiah. Here we see how full of joy he carries little Jesus in his hands, whom Mary has just handed over. Joseph has knelt down in respect and has brought the sacrifice prescribed for the less-well-to-do: a pair of doves.

A second motif hidden in this painting is Christ as ‘the Light of the world’. In the central panel Christ remains the central source of light, even though he is dead. His dead pale body, dominated by wanly blue, is emphasized by a purely white ‘clean’ (Mth. 27:59) shroud. The group of characters around Jesus, each in a gown with a proper primary colour form a wreath of colours. All this is in contrast with the dark background, which – loyal to the Gospel – evokes the nightly hour, but at the same time also – more psychologically – calls up the tragedy of this unjust execution. Those who are familiar with customary Marian prayers will undoubtedly associate The Visit to Elizabeth with the characterization of Mary: You who has given eternal Light to the world.

In his ode (Lk. 2:29-32) at The Presentation in the Temple old Simeon acknowledges the infant Jesus as ‘the Light of the world’. He does so to great joy of the eighty four year old widow and prophetess Anna, behind him. The Church had determined by order that a portrait of a living person was not to be depicted in the main scene of an altarpiece. So the portrait of Nicolaas Rockox, to be recognized as the man with the black hair and the black beard, figures on the right wing on the extreme left close to the frame. Being a confirmed Catholic he too recognized the Light in Jesus. With this contemporary portrait the Biblical significance becomes even more actual. After all Simeon’s ode is not only part of this one feast of the Presentation on 2 February: priests, religious and pious people conclude their days with it in the compline when praying the hours, to ‘go in peace’ – to meet a good night’s rest.

Even in the legend on the external wings both ideas of ‘carrying’ and ‘Light’ are linked up with one another. The hermit, who traditionally stands on the bank with a lighted lantern as a beacon for Christopher during his crossing, here actually illuminates the infant Jesus, who with his naked skin catches and reflects most light. It is the wise and pious hermit’s duty to indicate Jesus as ‘the true Light’.

Jesus on The Descent from the Cross in the central panel is the main character on which the composition of the three panels has been attuned. In the central panel Jesus’s head is at two third of the entire height of the painting. In the right wing the upward composition line runs from bottom right to top left, starting at Saint Joseph’s naked foot, running along his back to Mary’s hands, little Jesus’s head and so to the upward eyes of Simeon’s gaze towards Heaven. In the left wing from bottom left to top right you follow the impish maid servant up the stairs to the house of Elizabeth and Zechariah. The maid looks the beholders straight into the eyes to draw their attention to the most important tableau – a trick Rubens gratefully borrowed from Caravaggio.

The way Rubens succeeds in bringing the painting to life in a naturalistic way is unequalled. Just look at the beading drops of sweat on Saint Christopher’s forehead, the marbles in the Temple, the richly decorated cope Simeon is wearing, the sensual blond hair of Mary Magdalen and of Mary of Clopas. The magnificent coloration, with a whole range of hues per colour and an extremely playful reflection of light, such as in the clothes of the figures, is typical of Rubens.

Rubens had not long before returned from Rome and this is to be seen in the inspiration he found in classical antiquity. Saint Christopher was clearly inspired by Hercules Farnese (then in Villa Farnese, now in Naples). In the figure of Christ we notice the influence of the Laocoön Group (Vatican Museums), and in the Temple of Jerusalem one may recognize the coffered ceiling of the BasilicaA rectangular building consisting of a central nave with a side aisle on each side. On the short side opposite the entrance, there is a round extension, the apse, where the altar is located. The Antwerp Saint Charles Borromeo church is based on this basilica structure.

An honorary title awarded to a church because of its special significance, for example as a place of pilgrimage. There are 29 basilicas in Belgium, the best known of which are the Basilica of Scherpenheuvel and the Basilica of Koekelberg. Worldwide this is Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. These churches do not have the architectural form of a basilica.

of Maxentius at the Roman Forum. The seemingly antique garments of the Biblical characters receive a contemporary accent, for instance by Mary’s hat on the left wing and the papal camauroA red velvet cap trimmed with white fur, worn by popes. of ‘high priest’ Simeon.

The words of praise for this masterpiece are innumerable. For fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. Leopold Mozart, who saw it in 1765, it was just unbeschreiblich, ‘a work beyond any power of imagination’. In 1779 the Anglican minister Thomas Brand found that only this was already worth the journey. At the beginning of the French occupation, in 1794, Rubens’s masterpiece was transported to Paris as war booty, where it ended up as the showpiece of the Grande Galerie in the ‘museum of the world’, the Louvre. The altar however stayed behind and got lost during the clearance that followed. After Napoleon had been beaten the triptych fortunately returned to its original church in 1816, albeit two bays from its original position. Partly by coincidence, partly on purpose it received Rubens’s Raising of the Cross as a counterpart. Once again admirers came flocking. There is one testimony, from 1836, that we do not want to withhold. The French romantic author Théophile Gautier made the spiritual link between the hue of death of ‘the body of Christ’ and Holy CommunionThe consumption of consecrated bread and wine. Usually this is limited to eating the consecrated host., but further he has only eyes for the charms of Mary Magdalen with her profound love for Christ: Ah! Madeleine, Madeleine, que n’ai-je été ton contemporain! (Oh! Magdalen, Magdalen, what a pity I was not your contemporary !)

Not one painting by Rubens was copied so often as The Descent from the Cross. The Last Supper by Renaissance master Da Vinci has set the image of this Biblical scene worldwide (up till now). Rubens did the same with this Baroque masterpiece for Jesus’s descent from the cross until far in the 19th century.

If you want the contemplation of Jesus’s Descent from the Cross to grow into a probing experience, it would be best to listen to the story of the Passion as it is sung for instance in the Saint Matthew Passion by Johann Sebestian Bach: Mein Herz ist betrübt…