The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

After all death has not the last word: the tombs

Until the 18th century the deceased contributed to a stable church floor with their bluestone tombstones. But since so many people walk on this floor the ravages of time have worn off many an epitaph. Besides several tombstones went missing, especially because during the French Revolutionary Rule the floor was first removed so that it could be sold, and then, in 1800, laid out again so that the church could be re-opened. In this process quite a few tombstones were cut to make the paving fit around the pillars. Because the altars had been demolished, there were too many open spaces and these were filled up with tombstones from the former SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Michael’s AbbeyA set of buildings used by monks or nuns. Only Cistercians, Benedictines, Norbertines and Trappists have abbeys. An abbey strives to be self-sufficient..

The oldest tombstone is that of a lady called Katelijne ( 1307). To preserve it, it has been built into the wall of the chapterAll the canons attached to a cathedral or other important church, which is then called a collegiate church. In religious orders, this is also the meeting of the religious, in a chapter house, with participants having ‘a voice in the chapter’. house. Among those who could not reach eternal fame because their tombstone disappeared or wore down, are Antony van Dijck’s parents and the Florentine Ludovico Guicciardini ( 1589), to whom we are grateful for a popular historic description of the Low Countries. Not to be found either is the name of painter Erasmus II Quellinus ( 1678), who, together with his wife, was interred in her uncle’s tomb, canonSomeone who, together with other canons, is attached to a cathedral or collegiate church and whose main task is to ensure choral prayer. De Hemelaar, which did survive in the southern aisleLengthwise the nave [in exceptional cases also the transept] of the church is divided into aisles. An aisle is the space between two series of pillars or between a series of pillars and the outer wall. Each aisle is divided into bays.. Numerous tombstones, especially in the ambulatoryProcessional way around the chancel, to which choir chapels and radiating chapels, if any, give way., are deceptive, because originating from the former Saint Michael’s Abbey: the persons mentioned were actually never buried here. And so you can read for instance the names of the famous geographer and cartographer Abraham Ortelius ( 1598・southern ambulatory), of painter Jan Wildens ( 1653 ・ central northern aisle, next to the tower), and of Jan Brandt and Clara de Moy, parents in law of Pieter Paul Rubens (northern ambulatory). Filled with piety we mention the name of a man who survived three wives, namely in 1707, 1714 and 1726, and for nearly thirty years continued his life as a treble widower: Jan Baptist de Bruyn ( ), city messenger by profession (northern aisle).

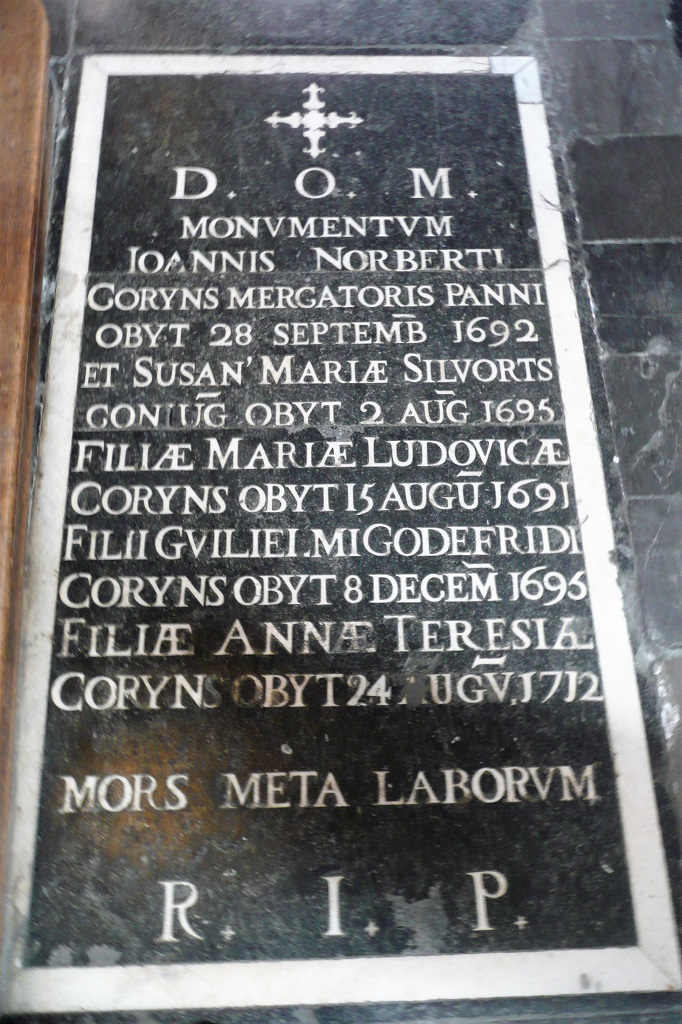

The tombstones all show identic patterns. On top there is the inscription ‘D.O.M.’, which is an abbreviation of Deo Optimo Maximo: (here lies) for the excellent and almighty God. According to the classic role pattern the man is mentioned first, sometimes with the addition of his profession, and then his wife: ‘syne huysvrouwe’ (his housewife). Although they did not work outside the house, it can be said that women did not devote themselves only to the humble tasks of washing and cleaning, but took care of the household in the full meaning of the word: ‘economics’ or management. Besides they were partly involved in the education of the children. At the bottom either the wish ‘R.I.P.’ (requiescant in pace – that they may rest in peace) is expressed, or the incitement ‘B.V.D.S.’ (bid voor deze zielen – pray for these souls). Rest and peace may sound a bit boring to us now, but it should be understood as: freed from fear and sorrow.

Already in the 17th century there were pleas for more ventilation in the church. The cadaverous smell that was given off when the crypts were opened to inter family members in them, was certainly not foreign to this. Due to emperor Joseph II’s 1784 prohibition of burial in churches and towns, parishioners then had to seek the last resting place of their beloved ones in the new graveyards Stuivenberg and Kielpark. Since time immemorial the deceased Antwerpians had been resting in the centre of their city, and amidst daily life, but now they came to lie far outside the city walls: an emotional revolution. Moreover this decree deprived the church of one of the important occasions for memorials. In the 19th century the remembrance of deceased persons was given a new shape in the form of donating stained glass windows.

The restoration works between 1973 and 1993 brought several objects to light: foundations and pieces of sculptures, owls’ pellets, skeletons of rats and bats, and even a well. Hundreds of skeletons and also different objects were brought up, including fragments of garments, buttons and pins, crosses and medals, coins and earthen pipes, ornamental combs and a manicure set: silent witnesses of life that walked on this floor in all its aspects.

The Antwerp ‘Golden Age’ also attracted Mr and Mrs Plantin-Rivière from Tours to make a fortune. Because in an assault his shoulder had been wounded, Christophe Plantin was forced to change his profession of leather-worker into type founder and printer. This change did not do him any harm. He even became ‘arch printer’ of the Spanish king. Plantin’s house and printing shop, together with the original furnishings now constitute an invaluable historic museum, which Unesco has recognized as part of World Heritage. At his death in 1589 the famous printer was given an ‘eternal’ resting place in the ambulatory of his parish church. Following the then fashionable altarpieces his funeral monument has also taken the form of a painted triptych.

The inner wings:

portraits of husband and wife and their children

Christophe Plantin and his son Christophe, who died young, are on the left wing, which is on the right hand side of Christ in the central panel and so in the place of honour, according to the social hierarchy of those days. Backed up by their respective patron saints, Christopher and John the Baptist, husband and wife are on their knees on a prie-dieu, folding their hands towards the Last Judgment in the central panel. On the open, printed book on Plantin’s prie-dieu there is the date ‘anno 1591’. Jeanne Rivière is accompanied by her five daughters and an untimely deceased little daughter. Just as their husband or fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. the ladies wear black clothes and lace ruffs: an allusion to the second, and very lucrative activity of the Plantin family: the lace trade.

The outer wings:

the patron saints of husband and wife

These grisailles are of an extraordinary quality: sharply drawn, detailed and, partly due to the depth effect, unusually plastic and dynamic.

On top of the renewed epitaph is Plantin’s motto: ‘labore et constantia’ (with diligence and constancy), allegorically represented by his emblem, a pair of compasses with a stationary and a movable leg. Justus Lipsius made this part of his tribute to the founder of the world famous printing shop:

PIETATE, PRUDENTIA, ACRIMONIA INGENII MAGNO,

great by sense of duty, wisdom and intelligence;

CONSTANTIA AC LABORE MAXIMO;

very great by diligence and constancy,

CUJUS INDUSTRIA ATQUE OPERA, INFINITA OPERA,

whose labour and dedication produced innumerable books,

VETERA, NOVA,

ancient and modern ones,

MAGNO ET HUJUS ET FUTURI SÆCULI BONO

for the benefit of this and centuries to come,

IN LUCEM PRODIERUNT

so that they could see the light

The central panel: The Last Judgment

Jacobus De Backer painted this scene in ca. 1580. Christ is sitting enthroned in the clouds, on the four symbols of the evangelists. The Last Judgment is being announced by three angels blowing the trumpet. In the heavenly court we recognize among others John the Baptist and Mary as two mediators to Jesus’s right. On earth, in the foreground, the middle ground as well as in the background, dead people rise from their graves and are immediately separated. The blessedUsed of a person who has been beatified. Beatification precedes canonisation and means likewise that the Church recognises that this deceased person has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. Like a saint, he/she may be venerated (not worshipped). Some beatified people are never canonised, usually because they have only a local significance. ones fly to Heaven, iconographically right of Christ, where they are welcomed by an angel with an olive branch, symbol of peace and happiness. The doomed ones, on Jesus’s left hand side, are cruelly abducted strongly against their will, to the blaze of hell, by devils with animal. faces Some doomed ones attempt to reach Heaven in vain: they are hit back by an angel with a sword and pulled down to hell by devils. Because the judgment is severe but just, the family asks for prayers as spiritual support: Tu qui transis, et haec legis, bonis manibus / bene apprecare (You who pass by and read this, remember with folded hands [prayingly] the good [that they have done] ).

In 1794 the painting was taken to Paris by the French occupier, and it returned to the church in 1816. Just as the funeral monument for Johannes Moretus this one too got a new monumental frame on the initiative of the Moretus family in ca. 1819. The white marble plaque was put up again and to crown it Willem Jacob Herreyns painted the portrait medallion of Christophe Plantin.

In the cathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is. there is a second marble funeral monument for bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’. Capello, which is very exceptional. Generosity typified him as well during his lifetime (in vita) as in his testamentary dispositions (et in morte), which indicated the poor as his sole heirs. Out of gratitude for his liberal gifts to the poor, the almoners had a funerary monument made by Hendrik Frans Verbrugghen or Artus II Quellinus in 1676, the year of his death. This monument was put up exactly above the counter of the Holy SpiritThe active power of God in people. It inspires people to make God present in the world. Jesus was ‘filled with the Holy Spirit’ and thus showed in his speech and actions what God is like. People who allow the Holy Spirit to work in them also speak and act like God and Jesus at those moments. See also ‘Pentecost’. masters at the southern tower, the so-called ‘Table of the Holy Spirit’, where the distribution to the poor took place.

The deceased person’s torso rises from the sarcophagus, as if the already decomposing body has been re-animated for a while. The eye sockets are hollow, the body is all shrivelled skin and bones. The theatrical effect is amplified by the way in which the bishop comes looking from underneath the black pallA square piece of cardboard covered with white linen that is placed on the chalice and/or paten to prevent dust or any other dirt from contaminating the wine or the host.. On the left extreme of the sarcophagus the mourning putto, which is a traditional element of a tomb, startles at the sudden apparition. With his left hand Capello is holding the shroud on the brim of the sarcophagus, while with his raised right hand [of which the index has broken off however] he is pointing at his stately official portrait of olden times, which is carried to Heaven in an apotheosis. Is this a momento mori, which wants to say as much as: ‘This is how I was in my prime’, or do the almoners want to self-confidently indicate how one hopes to deserve one’s heaven? This portrait, a relief medallion that was made post mortem, is one of Capello’s five sculpted portraits! The oval portrait medallion is framed by a laurel wreath and crowned with the bishop’s mitreThe ceremonial headgear of bishops and abbots. The front and back are identical pentagons pointing upwards., which is flanked by a bishop’s crosier crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept]. with an olive branch, which has disappeared. In a true apotheosis two floating angels blowing trumpets, and a putto carry the medallion towards Heaven. Originally there used to be a torch turned upside down, as a symbol of death.

The text on the scroll that is across the middle of the sarcophagus, honours the generous donator ‘as arch almoner, with which enough has been said’. Below the sarcophagus two putti are holding the bishop’s coat of arms, which is crowned with a green bishop’s hat, a bishop’s heraldic motif. The hat that on his escutcheon alludes to the name ‘Capello’ (Hat), however it is not the heraldic green bishop’s hat, but the red one of an archbishopThe bishop in charge of the archdiocese. In actual practice, this also means that he is the head of the church province.. A trace of ambition?

Following the famous Italian master of Baroque Bernini, the red veined marble is used for the tomb, the black marble for the draperies and the white marble for the figures.

Originally this monumental funeral monument was against a wall in Saint George’s Church. This late Baroque masterpiece by sculptor Peter I Scheemaeckers from 1688, has been preserved thanks to the French selecting it for the local museum.

It is surprising how many sayings have been represented here. A man of the world is standing with one foot in the grave, and he faces death. Death grins at him and pulls his sleeve: ‘here you’. The man tries to escape from Death but it will be in vain. However much he struggles, his last hour has struck. The same intriguing message is brought by Time, alias Chronos, on top, who holds up the curtain of the main scene with one hand. That ‘time flies’ is made clear by the man’s long beard and the wings. He is showing the young man – and not only him – the merciless hour glass. Originally he also carried a scythe. Time surpasses all earthly glory: each form of power and esteem, be it civil, military, ecclesiastical, intellectual or artistic, respectively in the form of a crowned globe, a club, a mitre and crosier, a book and a theatre mask. At one side a putto is carrying an inverted torch and makes clear: ‘you are blowing out your last candle’.

The man is holding a banderol in his hands on which a text has been engraved: “Joseph effugit mulierem non mortem” (Joseph could escape from the woman but not from death). It alludes to the story of Joseph from the Old TestamentPart of the Bible with texts from before the birth of Jesus. (Gen. 39:1-23). Potiphar’s wife wanted to seduce him and grabbed him by his garment (v. 12), but he left the garment in her hands and fled.

At the bottom of the medallion there used to be the maxim Mors omnia tollit (Death takes away everything), but in 1854 this was replaced by a vainer family coat of arms. The fact that man, after this fleeting life on earth, has an eternal life waiting at his final destination, is symbolised by the circular movement of the ouroboros, the snake trying to bite its own tail. The flaming sword and the palm show that one may count on justice at the Last Judgment and on a glorious entry into Heaven. Can you imagine that in our day someone would want to keep the memory to himself ‘alive’ in such a contemplating way?

- Our Lady’s Cathedral

- History & Description

- Preface

- Introduction

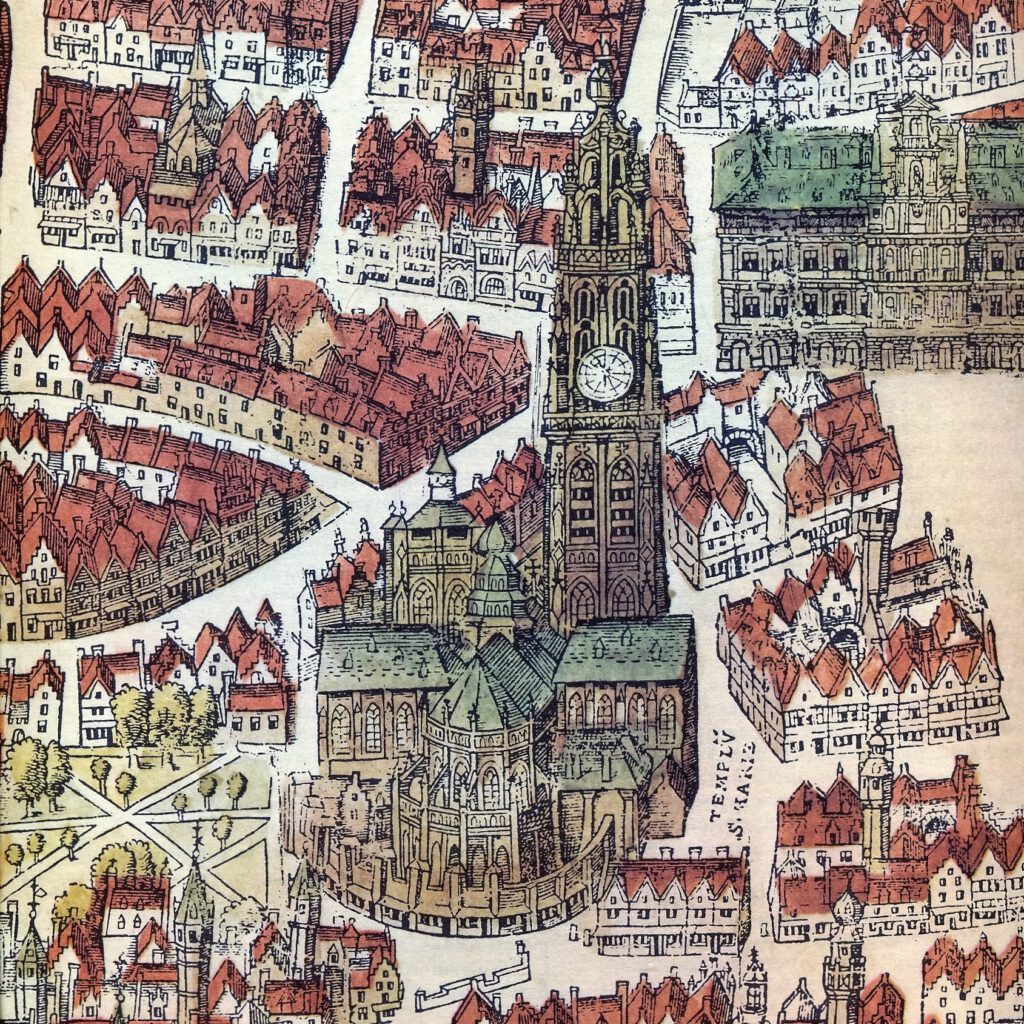

- Historical context

- A centuries-long building history

- A cathedral never stands alone

- Our Lady’s spire

- The main portal

- Spatial effect

- Mary’s Assumption (C.Schut)

- Erection of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- Descent of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- The Resurrection (PP.Rubens)

- Mary’s Assumption (PP.Rubens)

- The high altar

- The collegial choir

- The bishop’s church

- The parish church

- The pulpit

- The confessionals

- Caring for the poor

- The Venerable chapel

- Mary’s chapel

- Corporations and guilds

- The ambulatory

- Funeral monuments

- Praise the Lord!

- Pull all stops: the organs

- Cross-bearer (J.Fabre)

- Bibliography