The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

A construction history of centuries

The first proclaimers of Christian faith are said to have visited the precinct near the present Sint-Michielsstraat in the 7th century. There the first parish church was devoted to Saints Peter and Paul. After the raids of the Vikings in 836 the church was repaired and devoted to SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Michael, the angel who fights for the good cause and as such was very popular in the bellicose Middle Ages. In the 10th century or earlier – or, according to tradition, at the end of the 11th century through the agency of margrave Godfrey of Bouillon – a group of twelve clergymen, ‘canons’, were associated with this church: Saint Michael’s chapterAll the canons attached to a cathedral or other important church, which is then called a collegiate church. In religious orders, this is also the meeting of the religious, in a chapter house, with participants having ‘a voice in the chapter’.. Their first task was to pray the Liturgy of the HoursThe daily official public prayer in the Roman Catholic Church. On five [before the Second Vatican Council eight] moments spread over the day [and night], in abbeys, monasteries and chapter churches people come together to pray and chant these prayers. in community, but soon their worldly lifestyle incited the bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’. of Cambrai, whose diocese Antwerp was then part of, to intervene. He therefore made an appeal to a German from the Rhineland: Saint Norbert, the founder of the Premonstratensian order. He came to Antwerp in 1124 and urged the canons to live a more regulated life in a stronger community. Four of them agreed and founded the abbeyA set of buildings used by monks or nuns. Only Cistercians, Benedictines, Norbertines and Trappists have abbeys. An abbey strives to be self-sufficient. of Premonstratensian canons. So the first parish church was turned into a monasteryComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. church. Later this foundation evolved to become the famous St Michael’s Abbey, from which the abbeys of Averbode, Tongerlo and Middelburg were founded. Eight of the twelve canons chose more freedom and moved to the neighbourhood of a little eight metre (26 ft.) wide early Romanesque aisleless chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

devoted to Our Lady (first half 11th century), from which the chapter had its name since then.

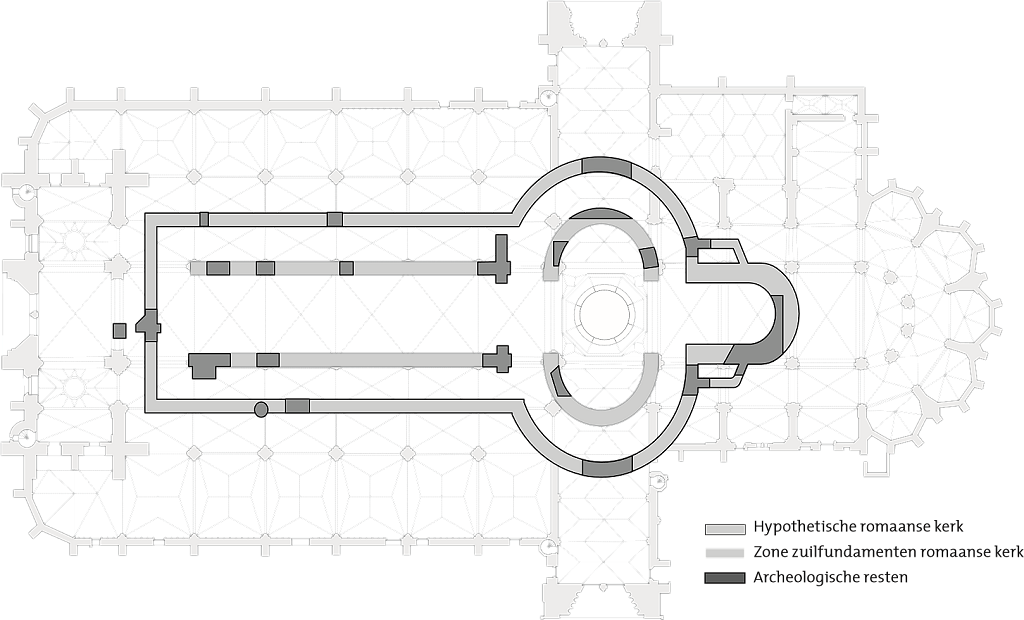

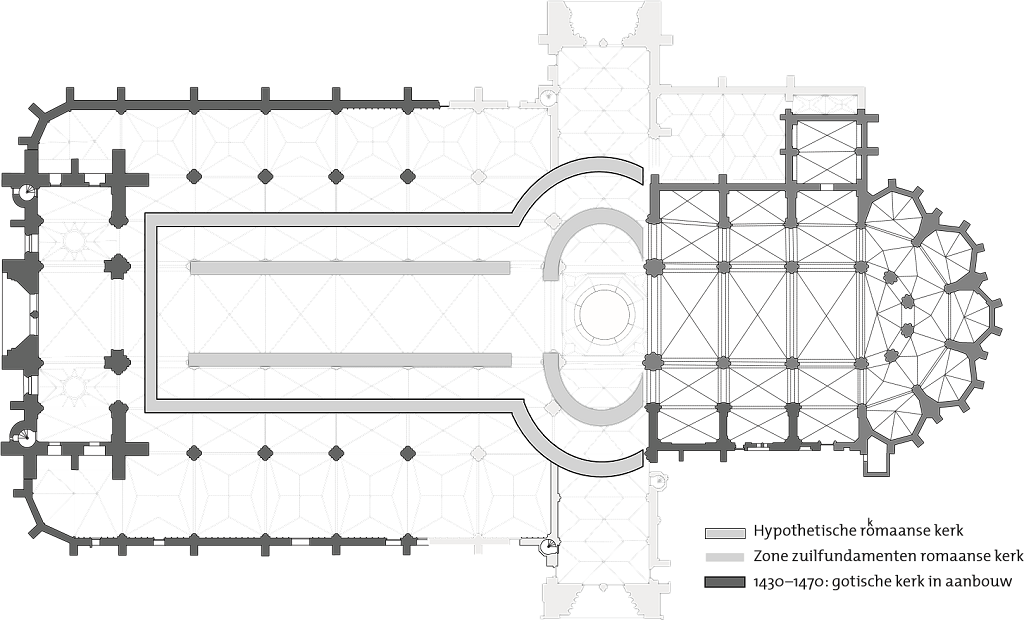

Thus in 1124 this chapel was elevated to a collegiate churchA church that is not a cathedral but does have a college (i.e., a group) of canons to conduct choir prayers. and the new parish church of Antwerp, positioned centrally between the already mentioned precinct of Saint Michael’s and the older settlement around the Steen. The construction of a new church was found necessary and the chapel was replaced by a real Romanesque church, which was surprisingly vast as could be concluded from the archaeological searching in the period 1970-1990. The house of prayer was 80 m (263 ft.) long and its shape can be compared to that of Sankta Maria im Kapitol in Cologne. The three aisled naveThe rear part of the church which is reserved for the congregation. The nave extends to the transept. had the same width as the present central naveThe space between the two central series of pillars of the nave., the inner aisles and part of the central aisles. The cloverleaf shaped Eastern part with a full ambulatoryProcessional way around the chancel, to which choir chapels and radiating chapels, if any, give way. had a width of no less than 42 m (138 ft.).

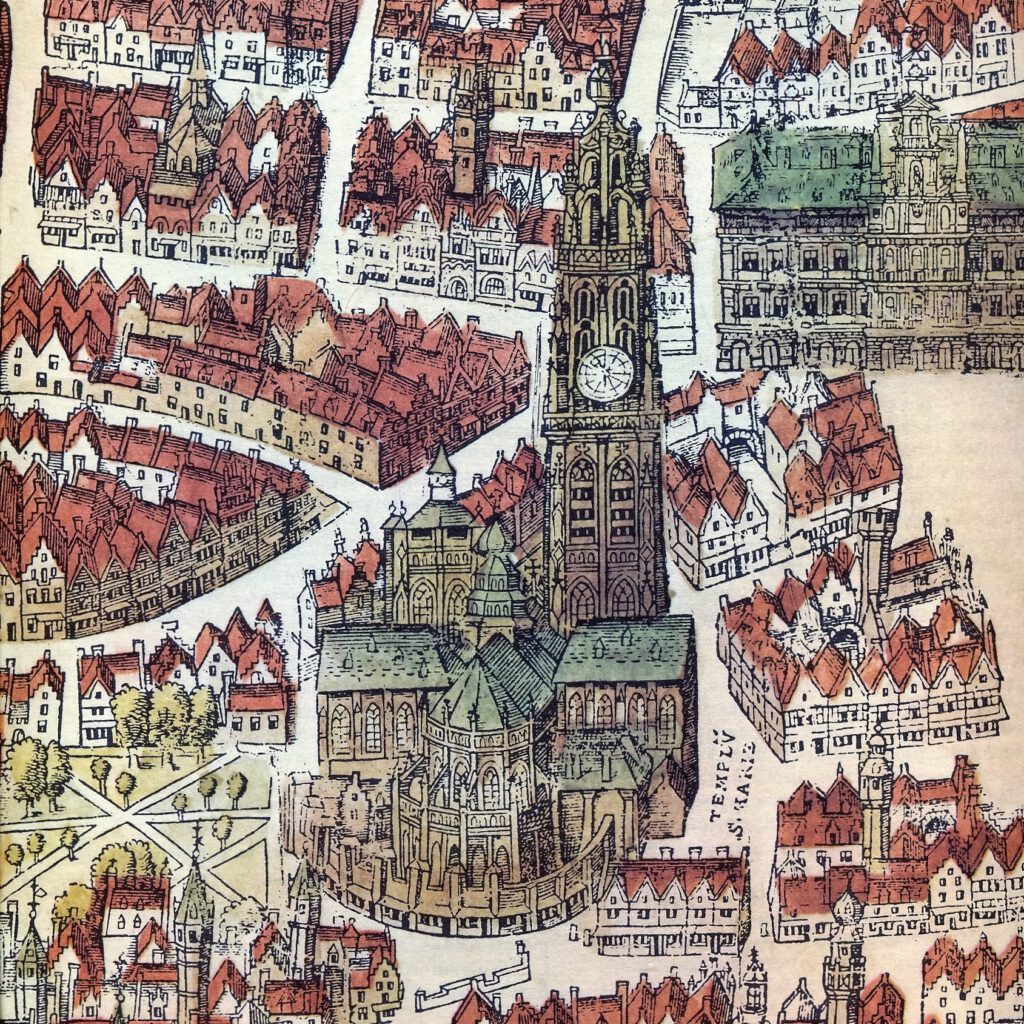

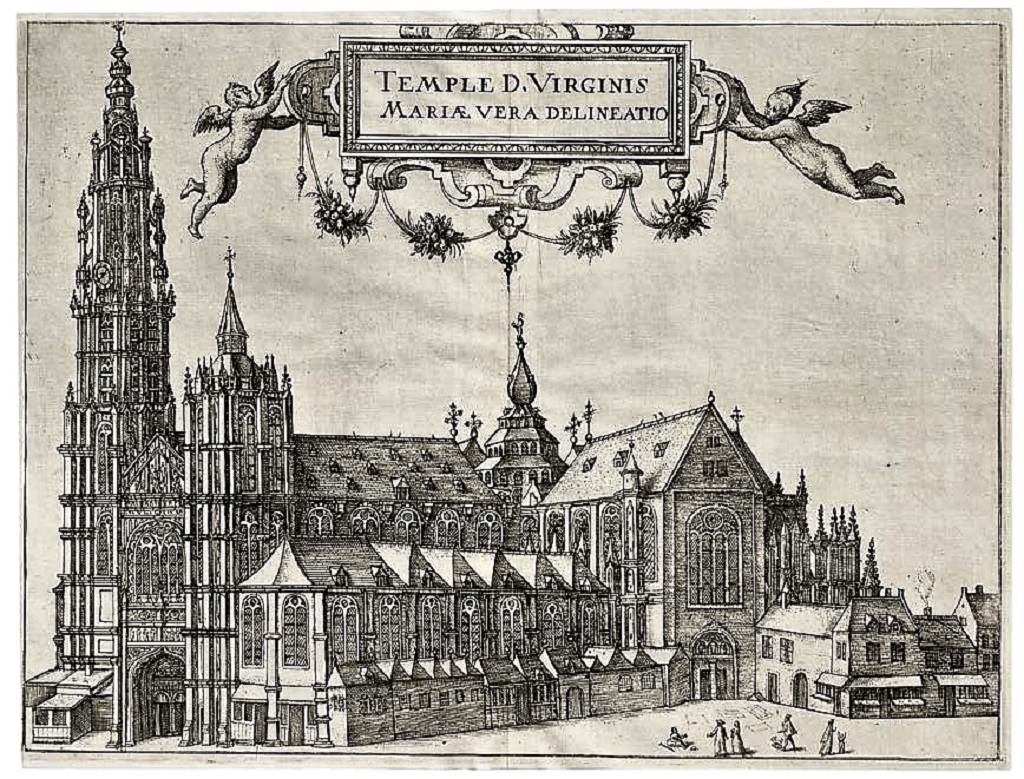

Because of the increasing importance of daily massThe liturgical celebration in which the Eucharist is central. It consists of two main parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The main parts of the Liturgy of the Word are the prayers for mercy, the Bible readings, and the homily. The Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the offertory, whereby bread and wine are placed on the altar. This is followed by the Eucharistic Prayer, during which the praise of God is sung, and the consecration takes place. Fixed elements are also the praying of the Our Father and a wish for peace, and so one can symbolically sit down at the table with Jesus during Communion. Mass ends with a mission (the Latin missa, from which ‘Mass’ has been derived): the instruction to go out into the world in the same spirit. – due to the aimed ‘effect’ for eternal salvation – it became more and more individualized: each officiating priestIn the Roman Catholic Church, the priest is an unmarried man ordained as a priest by the bishop, which gives him the right to administer the six other sacraments: baptism, confirmation, confession, Eucharist, marriage, and the anointing of the sick. ‘his’ own mass, with believers united for this particular devotion in a separate brotherhood at a private altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine.. In this way the number of chapelries increased: pious foundations that provided for the maintenance of an altar of devotion in a private chapel, including the salary of the officiating priest or ‘chaplain’. Thus for the important Marian devotion in 1294 the church was expanded with a ‘new construction’ (novum opus), which makes clear that the Gothic style had engrafted itself to the Romanesque building with at least one added chapel, long before the new church would be started in that style. Unfortunately not a single image of this church has come to us. Even if the seal of deanPriest – usually a parish priest himself – who coordinates the work of several neighbouring parishes [a deanery]. Lambertus de Rode, anno 1389, represented the most important church in his territory, the question would remain if this rudimentary representation (2.9 x 4.4 cm / 1.1 x 1.7 in.) with a Gothic spire on each transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right. of a Romanesque building – which is not impossible – corresponded with the reality of that day.

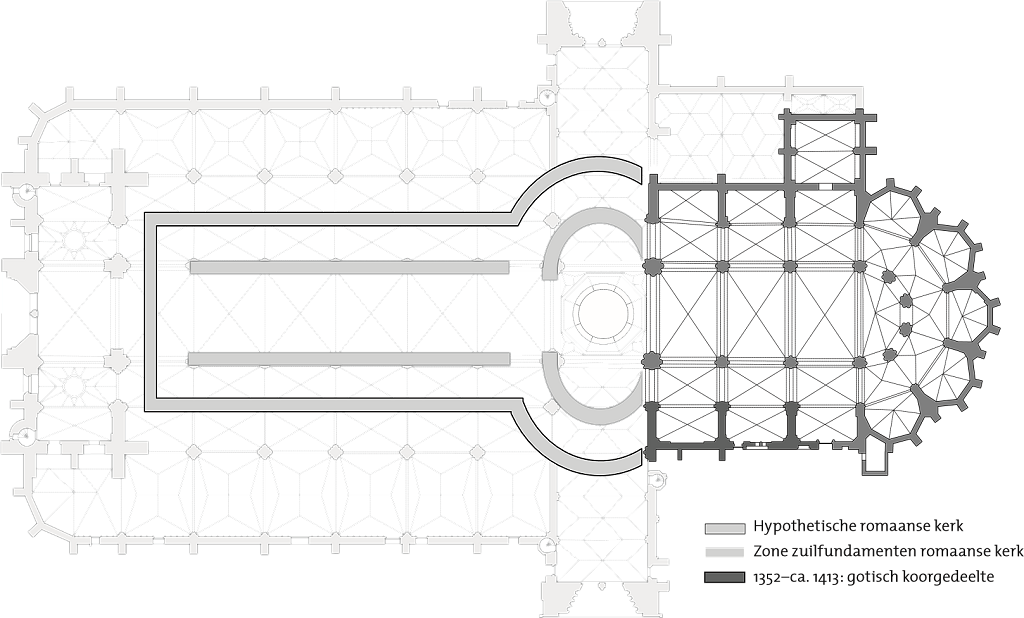

Due to the growing number of chapelry foundations a completely new construction was agreed. This is done in the ‘new style’, which will later be called ‘Gothic’. In 1352 the construction was started with the choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. in the East: the most important space for the canon’s daily Liturgy of the Hours. Because of lack of archives accurate dating is impossible. Only for the vaulting of the choir two exact dates are known: 1387 and 1391, the year the finishing of the choir could be started by installing a stained glass window. Together with the construction of the ambulatory, the radiating chapels and choir chapels the whole enterprise took about 60 years. Master builder Jacob van Thienen (before 1396-1403?) was also involved in the construction of the Brussels Saint Gudula’s church. In the meantime church life simply continued in the Romanesque nave.

Meanwhile the course of the river Scheldt changed substantially: an important turn for the further history of Antwerp and for the construction of this church. The river no longer found its way to the North Sea by the Eastern Scheldt alone, but by the new so called Western Scheldt. And so Antwerp came closer to the sea. But the sea itself also came closer to Antwerp, which could be felt especially at spring tide, when the church was flooded several times.

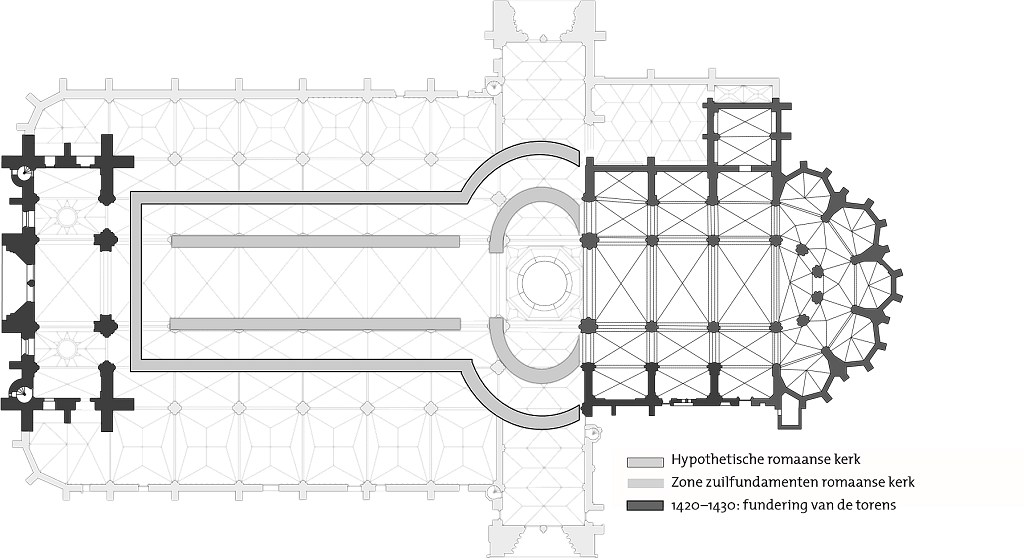

Because the nave, which had been planned to have six wide bays, would be longer than the Romanesque church, the western towers of the new church were outside the existing church, which permitted the execution of these immense time consuming constructions first keeping the old church standing for further use.

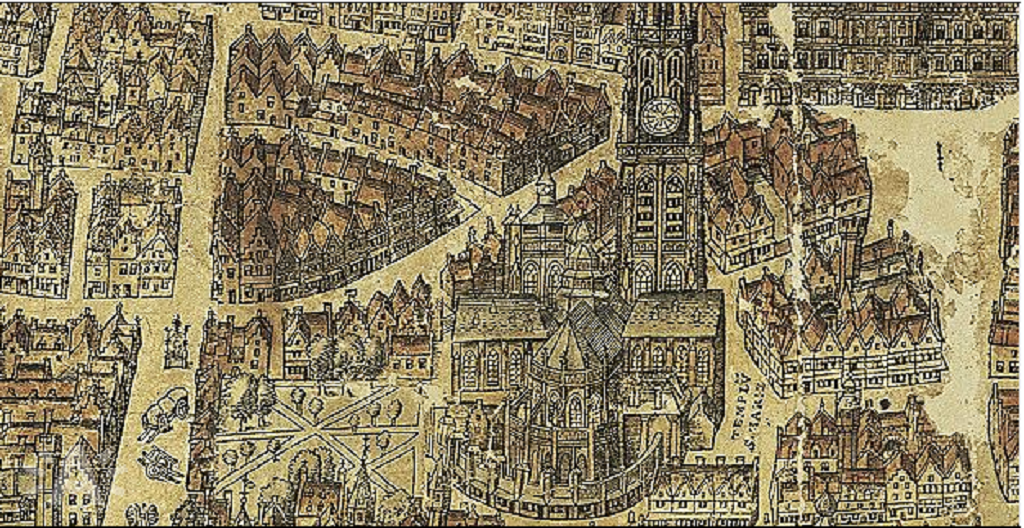

In about 1420, before founding the towers, the site of the church was levelled up three feet to stop the rising water. In 1420 and 1430 the foundations of the Northern and Southern towers respectively were laid under the lead of Peeter Appelmans. As such the length of the cruciform ground plan was definitively established. Since they were designed to be corner towers also the width of the church was indicated, which would consist of a nave and double isles at both sides.

While the stairs tower of the Northern belfry tower gives out onto the street, the Southern tower can only be reached via the church. Since it may be expected of stairs to fit perfectly to the doorway on every floor, starting with ground level, the stairs tower of the Southern tower must have quickly assumed the present floor level in the nave and the ambulatory in 1432. Because the floor was levelled up in the ambulatory the bases of the pillars there have completely disappeared under floor level, which has reduced the Gothic vertical dynamism there considerably.

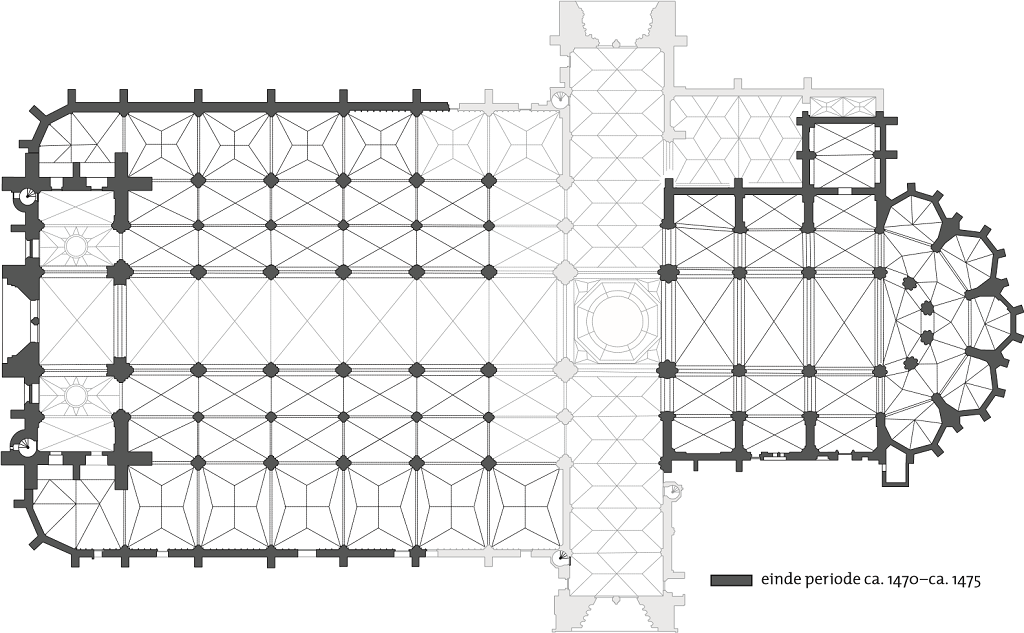

Because the number of foundations of chapelries kept on increasing and also the cash-rich crafts and guilds asked for private altars, already before starting the construction of the nave, the necessity was felt to enlarge the floor plan. In length this was impossible because the towers were already being built. And so a fifth and sixth aisleLengthwise the nave [in exceptional cases also the transept] of the church is divided into aisles. An aisle is the space between two series of pillars or between a series of pillars and the outer wall. Each aisle is divided into bays. was added. Because the extreme Southern aisle was meant to be the parish church, it has the same width as the central nave. The result is an extremely wide nave: 53.60 m (176 ft.). Under the lead of Everaert Spoorwater the four western bays of the extreme Southern aisle (1455-1469) and of the Northern aisle (finished ca. 1465) were constructed. By building these extreme aisles first the surface of the Romanesque nave remained comfortably amidst the four areas of the new Gothic church. Is it not logical that profit was taken from this opportunity to build in the old nave so that it could remain in use as long as possible? In any case in 1469 there was no question yet of pulling down ‘the old wall’ at the north end of the Romanesque nave.

To enable the construction of the extreme Northern aisle the last part of the interior of the former church was pulled down under the lead of Herman de Waghemaker from about 1478. This was the Gothic Our Lady’s Chapel, which had been added in 1294 and was replaced immediately by a new Our Lady’s Chapel in the uttermost Eastern bayThe space between two supports (wall or pillars) in the longitudinal direction of the nave, transept, choir, or aisle. in 1481-1482. In the adjacent bay the brotherhood of the Holy Cross was housed, although according to common symbolism this should have been in the Southern part of the church.

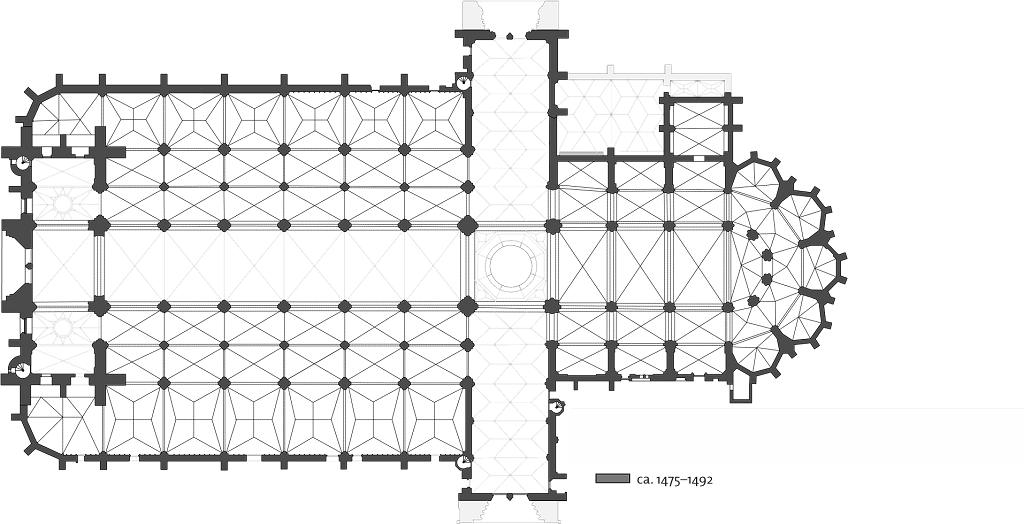

The two Western towers were constructed together as high as the belfry windows. In 1475 the construction of the Southern tower was stopped and five years later, after having finished the necessary bell-chamber, also the building of the Northern tower came to an end. In this way it became possible to focus on the construction of the central nave (1471-1487). Anyway there was a loss of income due to the founding of the new autonomous parishes of Saint George, Saint James and Saint Walburga, by which Our Lady’s Church had lost quite a lot of parishioners. This was partly compensated by the flourishing of the Antwerp harbour, causing a flow of immigrants and foreign merchants. The construction of the actual church progressed steadily. But there was also unexpected support: since the last quarter of the 15th century the devotion for ‘Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-op-het-staaksken’ (Our Lady at the stake) gave rise to numerous legends that contributed to success tangible in hard cash.

Once the new bell chamber had been finished, the last remainder of the Romanesque church could be demolished from 1482 onwards: the Northern tower, which until then had been the belfry of the City of Antwerp. This job explains why the building of the Northern transept (1487-1495) was started later than this of the Southern one (1481-1492). Moreover due to the enlargement of the church to one with seven aisles each transept needed one bay more than designed, if the cruciform ground plan was to be maintained. This is why for the foundations of the façade of the Northern transept more building land had to be bought, which explains the curve in the Southern alignment of Lijnwaadmarkt and Blauwmoezelstraat. In 1513 the adjacent Jerusalem Chapel was occupied by the Circumcision Guild. Next to the Southern ambulatory a series of buildings were constructed, including two sacristies and the chapter library (1482-1487).

Out of gratitude for the indulgence he had given to the church the year before, pope Julius II received his coat of arms on the boss that was put between the two towers in 1508. After having been suspended for a quarter of a century the construction of the prestigious Northern tower was resumed in 1502. In that year Dominicus de Waghemaker succeeded his deceased fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order.. To him the credit is due to have completed the tower. After only five years the octagonal drum was finished. In 1518 the Northern tower was crowned and the cross was consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words..

It could be expected that once the Northern tower had been completed the churchwardens would have made the Southern tower a full twin tower, but then we overlook the ‘Golden Age’. The boom in the Antwerp harbour was partly thanks to Maximillian of Austria, who in 1482 had given privileges at the expense of Bruges. Thanks to their economic success within a craft a number of subsidiary professional groups became independent crafts. Not only did crafts and guilds create distinct profiles for themselves by private guild houses on the Great Marketplace,but the richer among them also had social service centres or ‘alms-houses’ for members who had difficulty taking care of themselves. But all of them, without exception, were attached to having a private altar – preferably in the main church – and so the number of altars in Our Lady’s Church grew to no less than 57! The fact that also newcomers wanted to show themselves resulted in the umpteenth enlarging of the church, this time also in the length. For this the existing ambulatory, radiating chapels and the Southern choir chapels would be partly demolished.

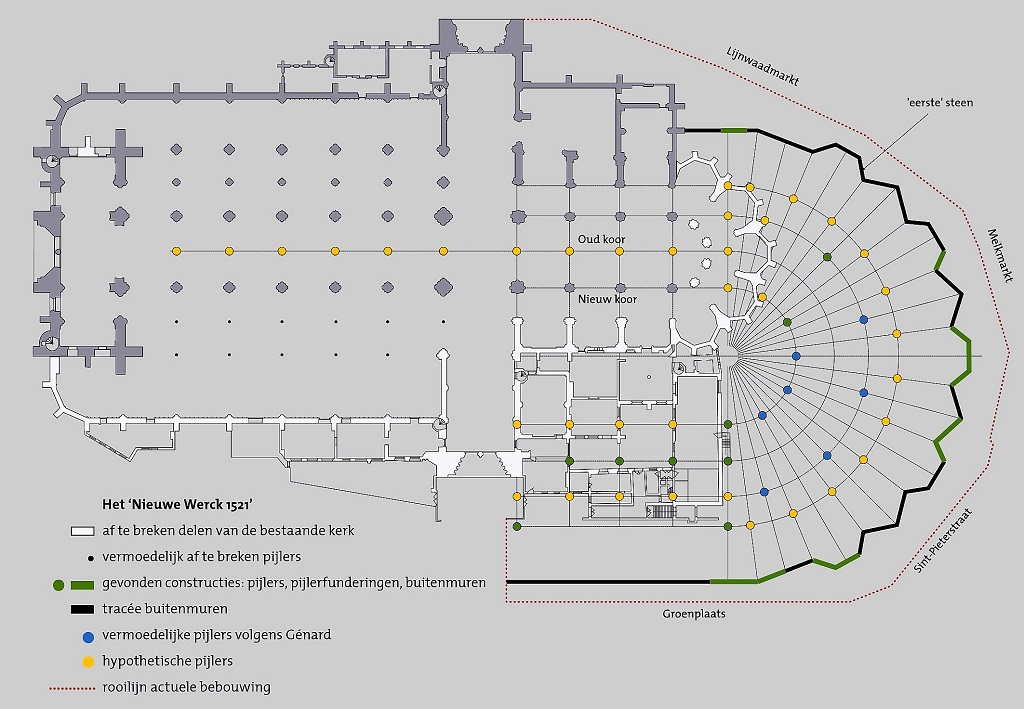

By adding a row of pillars the present, vaulted choir would be divided into two naves, just like the present central nave, which had not yet been vaulted then. In this way an extra row of places for altars would have been created. Thus the present central nave would have been downgraded to aisles. The new central nave would have had immense dimensions, although it is not clear what the elevation would have looked like. It is logical that all five Northern aisles would have been copied at the Southern end. The result was to beat all records: an eleven aisled church! The pillars of the present choir would then form a new, double ambulatory around an immense sanctuary, with radiating chapels that would more look like mini churches. Megalomaniac, unprecedented!

The church architectural ambitions of the Antwerpians apparently knew no limits. According to this megalomaniac plan of Dominicus de Waghemaker and Rombout II Keldermans the surface area of the present church would at least have doubled. If a symmetric frontage was wanted the new twin tower had to be moved South. This is the reason why finishing the present Southern tower was superseded. Also the project of an octagonal crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept]. lantern or tower, which was started in 1497-1498, was stopped in 1521 because the wider central nave of the ‘New Work’ that was planned, was to be provided with an adapted crossing construction.

Hardly had the Northern tower been completed when this audacious ‘New Work’ was started – not on the initiative of high ecclesiastical or civil authorities, but under the pressure of the ambitious guilds and crafts. The honour of laying the foundation stone for such an ambitious project was reserved to emperor Charles V, on 15 July 1521. Loyal to tradition the enterprise was started in the East with the construction of the new choir and ambulatory. In twelve years’ time the complete external wall of the radiating and choir chapels and at least eleven pillars were built to a height varying between 5 and 7 metres (16 and 23 ft.).

But due to the catastrophic fire in the night of 5 to 6 October 1533 the megalomaniac dream turned into a colossal washout. The fire of a carelessly extinguished candle at the Saint Gummarus altar of the woodworkers spread out over the roofs. ‘Little sparks kindle great churches’, according to rhetorician Cornelis Crul, who devoted a remarkable chronogram to this disaster. The rafters of the central nave, which had not been vaulted yet, crashed down to destroy the magnificent late Gothic retables. The blaze of Europe’s most famous church was great news and spread like a wildfire. In Freiburg Desiderius Erasmus, who found himself in several areas of tension, quickly wrote to his friend, the Antwerp cannon Conrad Goclenius. He found this disaster threateningly inauspicious and called it: ‘An omen that frightens me’.

Because the immediate restoration of the existing church was given priority, the ‘New Work’ was temporarily suspended. The heavily damaged pillars of the central nave did not get back their pretty nature stone mantles, but were only plastered. This solution was not only due to a quick or cheaper way of working, but at least as much to the Renaissance preference of round columns. Less than a year later, in 1534, the wooden crossing lantern was finished also in Renaissance style. Possibly this was meant to be a fast, temporary solution before the ‘New Work’ could be continued. Also the absence of plans to vault the central nave and the transepts frame in this supposition. Still it did not take long before the spectacular plans for the megalomaniac construction project were definitively filed.

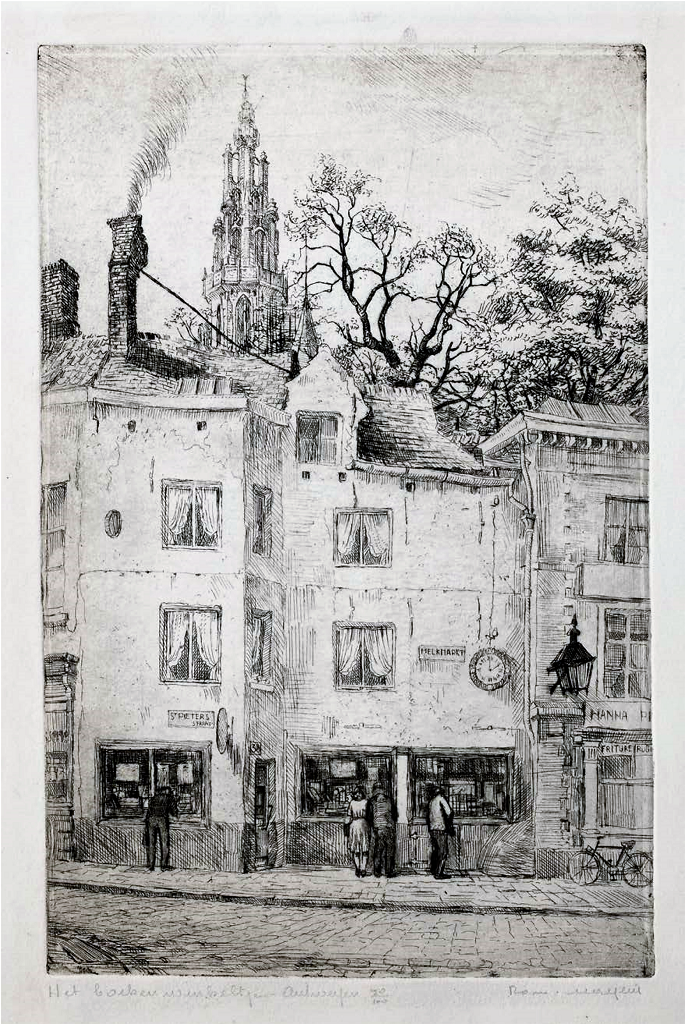

The onset of the newly planned choir still determines the outlook of the streets Lijnwaadmarkt, Melkmarkt, Sint-Pietersstraat and the Groenplaats. In order to make the investment as much cost-effective as possible about thirty small houses were built against the new exterior wall, often with a shop frontage. In this way it cannot be seen from the street. So as to use the enclosed space within the high wall as optimally as possible, it was levelled up. Some of the pillars were used as springing points for the ground floors of the ‘papenhuis’ (the priests’ house) with a library, which at the Southern end had a view on the Green Graveyard (the present Groenplaats). In this way as much daylight as possible could come in. The space between the remaining pillars was covered with sand. Hence the artificial mound that is now the garden of the presbytery, which until the French Rule was known as ‘het Papenhof’ (the priests’ garden).

On the occasion of the rearrangement of the garden of the presbytery, which had been re-acquired, city archivist Pierre Genard recorded eleven pillars: the so-called eleven pillars plan. Not less spectacular was the discovery of the tablet commemorating the laying of the foundation stone by emperor Charles V, when the house Lijnwaadmarkt 20 was pulled down in 1881. The churchwardens entrusted this unique testimony of the ‘New Work’ to the Antwerp Museum of Antiquities, but now – alas! – it seems to have disappeared.

Thanks to works on the sewer system in 2012 onsets of foundations of three more bundle pillars came to light. Their position can still be indicated thanks to the pattern in the renewed paving.

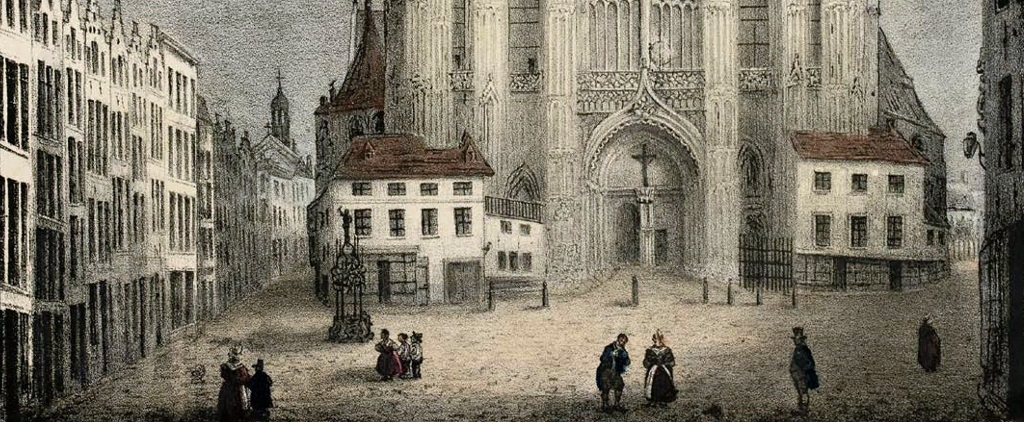

Two colourful stained glass windows give evidence of the resilience after the fire. Both are to be thanked to wealthy foreign families that had settled in Antwerp. The adoration of the Magi was donated by the Dassa-Rockox family and The conversion of Saul (to Paul) by the immensely rich bankers family Fugger, whose residence in Steenhouwersvest was marked by the tallest civil tower in town. Although the prestige of the grandiose church was not increased by being enlarged, it received a higher hierarchic title, because in 1559, due to the foundation of the bishopric with the same name, the main church of Antwerp was elected as if self-evident for the bishop’s see. Then the church became Antwerp ‘Cathedral’.

This administrative reorganisation however had little impact on the protesting organisers of the ‘Iconoclast Fury’, which caused horrible havoc here in 1566. Destructiveness raged through the country as a release of hostile resentment against the Catholic Church. In spite of being well orchestrated the actual moment of the event was coincidental: around 15th August, the feast of the patron saint with the traditional Marian procession. Numerous Antwerp retables – which many would envy us – were smashed to pieces. Even children were allowed to take part in the game: The heretics have also completely spoilt and destroyed the beautiful hymnbooks … as well as three pretty organs, and the children ran blowing pipes along the streets, selling them to each other playfully. Immediately after this the restoration of the altars was vigorously started.

The second campaign against statues and pictures, fifteen years later, took place by order of the owners of the church. As they had a position of power in the Antwerp municipality, the Calvinists forbade Catholic religious practice and confiscated the churches completely in 1581, although before there had been a two years’ period of tolerance. True to their austere form of religious practice they commanded that the church be cleared of all ‘papist’ furniture and that the altars be removed. Several guilds and crafts succeeded in carrying their precious retables to safety. After this triple reduction only the architectural frame was left of this largest treasury of late Gothic art in the Low Countries.

For four years ‘Holy Communion’ was celebrated in the choir, until in 1585 Alexander Farnese brought the town again under the lawful Spanish rule, restored Catholicism and forced it on the Protestants. The retables were put back or soon replaced by new ones in the spirit of Counterreformation. In twenty years’ time most brotherhoods, crafts and guilds succeeded in redecorating their altars with either a painted tryptic or a single altarpiecePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella.. For this they could appeal to a great many Mannerist artists of stature: Otto van Veen, Maarten de Vos, Frans I Francken. Those that due to circumstances waited some time, such as the guild of the arquebusiers (1611) and the chapter (1625), could make an appeal to Peter Paul Rubens’s talent. There were also some families who commissioned a funeral monument tryptic by him. Later the Italian artistic fashion dictated a removal of the wings of the tryptics so as to transform the altars into – preferably marble – portico altars. In the Baroque the focus shifted more and more to three-dimensional art: either carved wooden church furniture, or sculpted marble funeral monuments. The rich Baroque scenery of the 17th century cathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is. can still be admired in tens of paintings of church interiors, often linked with the name of Peter I Neefs.

In 1614, at the time of the archdukes, the central nave was finally vaulted followed by the Northern transept. On the keystones figure the sculptured coats of arms of the chapter, of the duchy of Brabant, of the Margraviate, of the town, of the Infanta and Archduchess Isabella and of Archduke Albert. The Northern transept was finished with the stately stained glass window in the frontage (Cornelis Cussers after a design by Jan Baptist Van der Veken, 1616). One year before in the Eastern side of this transept stained glass windows had been put, among which there is the window in honour of Our Lady of Scherpenheuvel, which also pays tribute to both sovereigns.

The end of the 18th century meant new misfortune, this time in the name of Enlightenment, starting with the ecclesiastic interferences of emperor Joseph II of Austria. One of the things he forbade, in 1784, was burial in churches and cities: a drastic change in the use of the church and the adjacent graveyard. Another radical law of the ‘emperor-sacristan’ was the abolishment of fraternities in 1786.

At their conquest in 1794 the French moved a few dozens of paintings to Paris as war contribution. Also the cathedral was robbed of its most famous works by Rubens. As a consequence of the French revolutionary laws the cathedral became national property in 1797 and the chapter was abolished. The most important paintings got a museological destination in the Antwerp École Centrale. Then the entire furnishings were sold publically. There was even threat of complete demolition! City architect Jan Blom was commissioned to make the necessary plans and provide a bill of quantities to this end. Because the churchwardens’ room was used as an office for the administration, it is the only one that has preserved its interior completely, including the Birth of Christ by Maarten de Vos (1577). The original painting on the mantelpiece Landscape with rest during the flight into Egypt by Joos de Momper and Hendrik van Balen (ca. 1620-1630) with caring Joseph carrying provisions to Mary and her Child, may be interpreted allegorically: the churchwardens, who ‘with due diligence’ are responsible for the material care for the church.

Soon after Napoleon had taken power he concluded a concordat with pope Pius VII. Anticipating this the main church of Antwerp was given back to religious service in the beginning of 1800. It was reopened as a parish church, no longer as a collegiate church, nor as a bishop’s church, because the Antwerp diocese had been abolished and so the church lost its title of cathedral. The rubble had to be cleared up and the floor, which had been broken up, had to be laid again. For the necessary repair Napoleon even gave a grant of 15,000 French francs to the fabric committeeAn official institution that manages the material resources needed for worship in a parish. In concrete terms, this means that it handles the (re)construction and maintenance of the church building, the purchase of liturgical vestments and objects, the payment of the organist’s wages and possibly the staff’s, … The fabric committee has revenues from particular intentions, special celebrations (especially weddings and funerals), a part of the collection and possibly from renting or leasing property.. Thanks to prefect Charles d’Herbouville many a work of art soon found its way back from the museum to Our Lady’s Church. Jan Blom’s first intervention in the church interior was repairing the Gothic profile of the pillars. Even though this was done in cheap stucco it can be seen as a first step towards rediscovering Gothic.

When refurbishing the empty church after 1801 in a first stage furniture was bought coming from convents and monasteries the French had abolished. These side altars, communionThe consumption of consecrated bread and wine. Usually this is limited to eating the consecrated host. rails, pulpit and confessionals are all Baroque. On 5th December 1815, very soon after the Battle of Waterloo, the paintings returned from Paris and were welcomed in Antwerp with bell chiming. It took another few months before the paintings by Rubens could be admired again in the church. The altars of the side-chapels of Our Lady and the Venerable chapel (1824-25) were rebuilt in the traditional Baroque style partly by reassembling recycled material. In the meanwhile Jan Blom had rebuilt the high altar in Classicist style (1822-1824).

Mid-19th century, a Gothic revival provided for a refurbishing in the neo-Gothic style with dozens of stained glass windows, as well as the monumental choir-stalls, the side-altars in the choir chapels and radiating chapels, the western rood loft and the monumental closed porches. Especially new devotions got personal chapels with neo-Gothic altars such as the Sacred Heart (of Jesus) in 1844, popular saints such as Saint Antony of Padua, or those who had just been beatified or canonized.

None of the two world wars seriously damaged the church. The most precious paintings were taken to the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in 1914. In the Second World War they were stored in bunkers in the church itself. After the First World War the last choir chapelA chapel along one of the straight side walls of the choir. was devoted to Our Lady of Peace in 1924.

In 1961, Antwerp became an autonomous diocese again. The church with its bishop’s see (‘cathedra’) could be called ‘cathedral’ again, and it is the Province – and no longer the town – of Antwerp which is responsible for its well-being. The Province decided for an overall restoration, a gigantic project, as well for the extent and complexity of the monument, as for the hidden surprises which history had (and still has) in store. Three stages can be distinguished: the nave (1973-1983), the choir and the transepts (1986-1993) and the radiating and choir chapels (1993-2014).

The central nave and aisles (1973-1983) were restored according to the then current aesthetic view with a preference for white, bare stone. When the stucco of the pillars had been chiselled off it became clear how severely their natural stone mantle had been damaged by the 1533 fire and that it had to be renewed for the greater part on nearly all the pillars. The aesthetic accent of this restoration philosophy also has a downside: in an aggressive way 15th and 16th century polychrome paintings on vaulting ribs and keystones have been irrecoverably sandblasted off.

In the second stage, the restoration of the choir and transepts (1986-1993) an historical approach was pursued. The church was approached as a whole in which all the different art styles should be present, even the neo-Gothic style, which until then had been looked at contemptibly. Not only is there a striking respect for the past, which has been increasing since the Romantic era, but also a respect for the future. Because it was not obvious which layer of paint from the 32 layers should best be removed and which should remain, the option was taken to put an extra layer of white paint above them all to protect the mural paintings, hoping that in the future there will be better restoration techniques allowing all the interesting layers to be exposed. This type of reasoning runs parallel with our ecological care for the future. Another result of this historic accent is the construction of an archaeological cryptOriginally an underground burial chapel in which the relics of the saint to whom the church is dedicated were kept and venerated. The crypt is usually found under the choir. In a pilgrimage church it mostly has two staircases leading to it. This made it easy to organise the influx of pilgrims: they went down one flight of stairs and up the other. underneath the sanctuary, with fragments of the Romanesque church in situ and a few painted tombs.

The third stage of the restoration works (1993-2014) under the lead of architect Rutger Steenmeijer included the ambulatory and the adjacent chapels. It was chosen to refresh the mainly neo-Gothic polychrome wall and vaulting paintings. The exterior restoration has mainly brought to light the ravishing white stone decorative architecture of the choir. This can be admired best from the cathedral garden. As it is the place of the ‘New Work’ this garden was listed as a precious archaeological site in 2014: a testimonial of a dream that never came true…

- Our Lady’s Cathedral

- History & Description

- Preface

- Introduction

- Historical context

- A centuries-long building history

- A cathedral never stands alone

- Our Lady’s spire

- The main portal

- Spatial effect

- Mary’s Assumption (C.Schut)

- Erection of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- Descent of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- The Resurrection (PP.Rubens)

- Mary’s Assumption (PP.Rubens)

- The high altar

- The collegial choir

- The bishop’s church

- The parish church

- The pulpit

- The confessionals

- Caring for the poor

- The Venerable chapel

- Mary’s chapel

- Corporations and guilds

- The ambulatory

- Funeral monuments

- Praise the Lord!

- Pull all stops: the organs

- Cross-bearer (J.Fabre)

- Bibliography