Galleria fotografica gigapixel

Nel 2021, Gilles Alonso, un fotografo francese che vive ad Anversa, ha contattato TOPA.

È specializzato nella fotografia ad “altissima risoluzione”, conosciuta anche come Gigapixel.

Con questa tecnologia, un’immagine può essere ingrandita quasi all’infinito.

In questo modo, un dipinto rivela dettagli che non si vedrebbero mai in una chiesa o in un museo.

In altre parole, si guarda con gli occhi del pittore!

Si è offerto di fotografare un quadro con questa tecnica in ciascuna delle cinque chiese turistiche di Anversa.

Il risultato è sorprendente!

I seguenti dipinti possono già essere ammirati in questo modo.

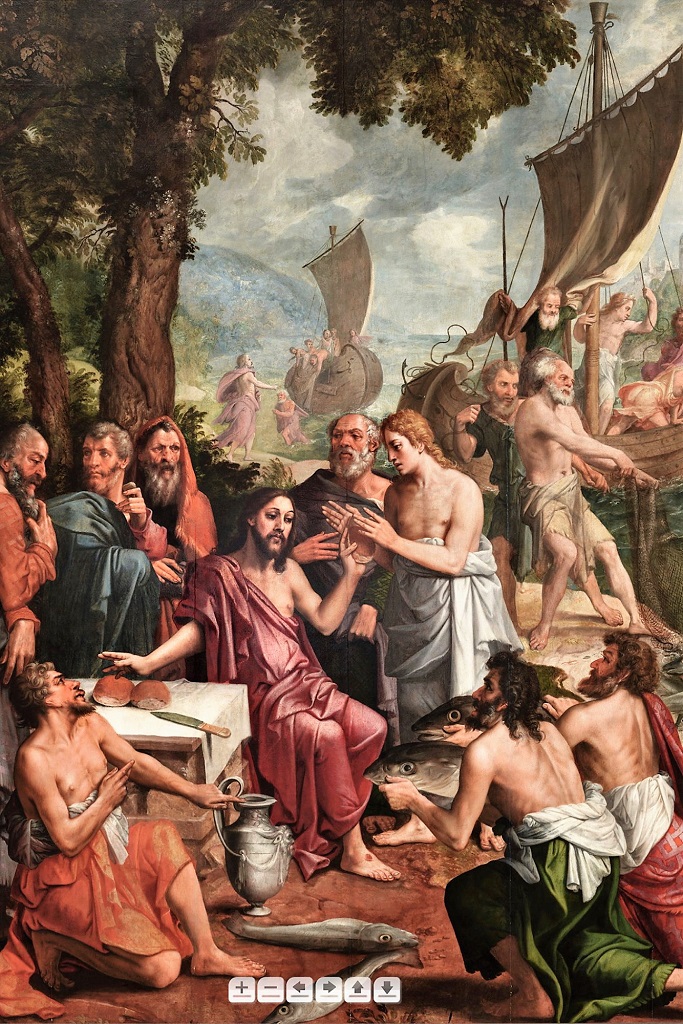

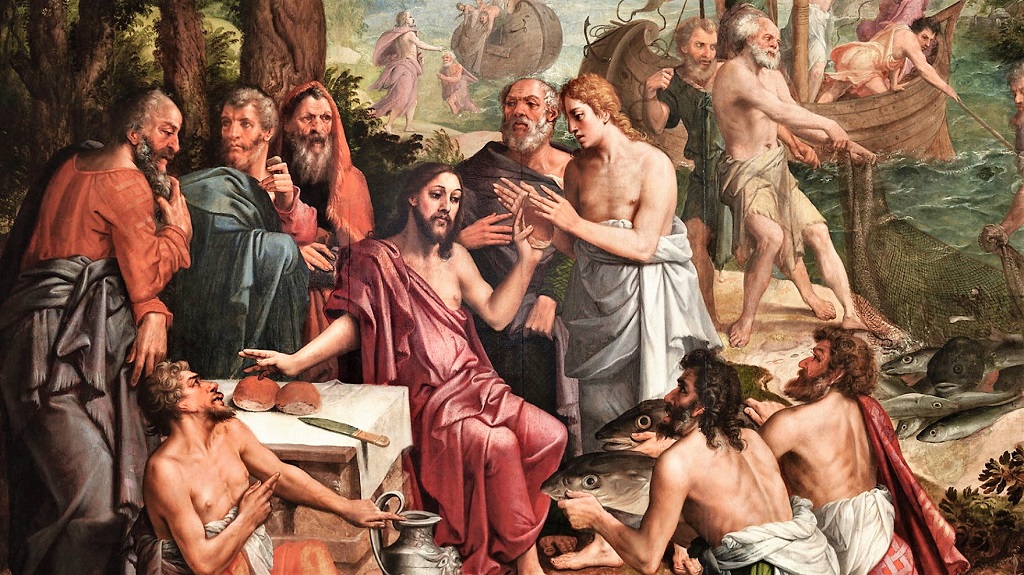

Puoi ingrandire e rimpicciolire e spostarti usando le icone in basso o il mouse.

Nella Cattedrale di Nostra Signora: “La presa miracolosa” di Hans van Elburcht

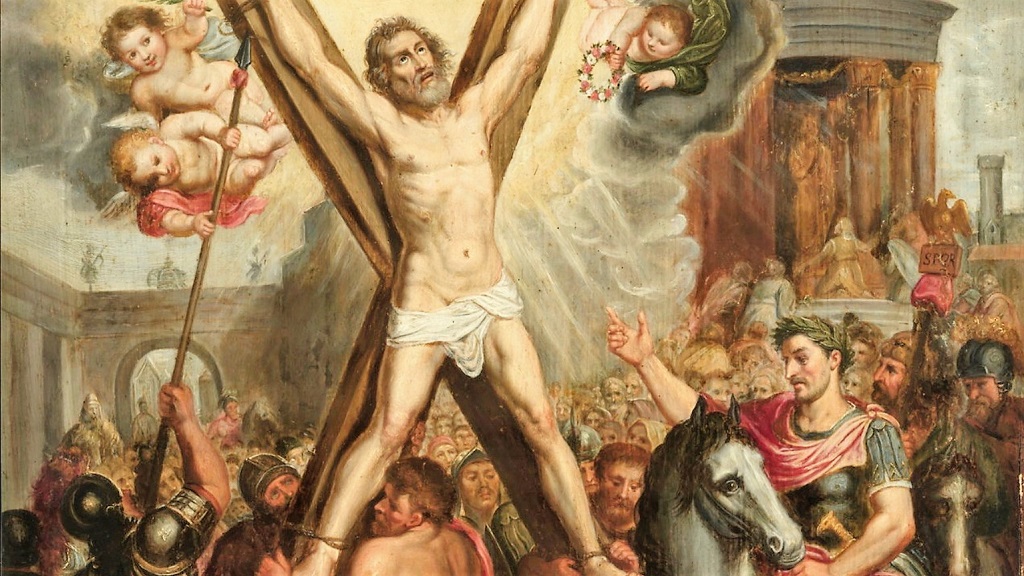

Nella chiesa di Sant’Andrea: il modello per “Il martirio di Sant’Andrea” di Otto Van Veen

Nella chiesa di San Carlo Borromeo: “L’incoronazione di Maria” di Cornelis Schut

Nella chiesa di San Giacomo: “Madonna col Bambino” di Peter Paul Rubens

Nella chiesa di San Paolo: la “Disputa sul Santissimo Sacramento” di Peter Paul Rubens

Qui sotto c’è una descrizione dettagliata di ognuno di questi dipinti. (in inglese)

The fishmongers’ altarpiece by Hans van Elburcht, ca. 1560, reflects the devotion for their patron saints: the apostle-fisherman par excellence, Peter, the most important one, is in the central panel and on the left panel of the predella; the apostles Philip and James the Less are on the wings.

The fishmongers’ altarpiece by Hans van Elburcht, ca. 1560, reflects the devotion for their patron saints: the apostle-fisherman par excellence, Peter, the most important one, is in the central panel and on the left panel of the predella; the apostles Philip and James the Less are on the wings.

The main scene in the foreground was inspired by a print from 1556 by Pieter van der Heyden, which in its turn goes back to a work by Lambert Lombard. Because it was adapted to a portico altar the triptych was made smaller, probably in 1621, when the fishmongers’ altar was moved to the western pillar of the central nave. Unfortunately we do not know anymore what the complete central scene looked like originally.

The central panel shows in three acts successive scenes from the story of the miraculous catch of fish (John 21:1-14). The story is to be read from the background top left [I] to the middle ground centre right (II) and then back to the foreground on the left [III]

[I] On the initiative of Peter six apostles join him to go fishing on Lake Tiberias, but they do not catch anything. At the apparition of the Risen Christ (✛) on the bank there is a miraculous catch of fish. While the other six apostles do everything they can to hoist the full nets aboard, Peter (A1) wades through the water to Christ.

[III] ‘The other disciples came in the boat’, ‘dragging the net with the fish’. At Jesus’s demand for some of the (miraculous) fish that they have just caught Peter (A1) drags the rich catch ashore.

[III] In the foreground the emphasis is on the supply of the ‘large fish’, which Jesus (✛) gave them in His turn together with the bread. Peter (A1), once again as (second) main character, has knelt in front of Jesus, together with young John (A2) with the blond hair.

The wings focus on the two other patron saints of the guild. The left wing shows the baptism of the Ethiopian eunuch (alias ‘the Moor’) by Philip (Acts 8:26-40) (Rotterdam, Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum). On the right we see the martyr’s death of James the Less (Saint-Ghislain, Convent of the Sisters of Mercy).

In the last quarter of the 16th century, presumably after the restoration of Catholic worship in 1585, the two panels of the predella were added, by an anonymous artist probably from the surroundings of Ambrose Francken. Here Jesus invites fishermen to follow him: they will be the first apostles. On the left panel (iconographically right) with The calling of Peter at the miraculous catch of fish (Lk. 5:1-11), one can see how in the background fish is being supplied on the quays. Its location reminds of the Antwerp Wharf with the fish market in front of the Steen. On the right panel another pair of brother-fishermen is shown at The calling of James the Greater and John (Mth. 4:21-22, Mk. 1:19-20). They leave their father Zebedee behind in the boat. Due to the adaptation to the new altar James in grisaille disappeared from one outer wing and Philip on the other was severely damaged.

The modello hangs in the corridor of the museum. The original hangs on the south side of the sanctuary.

The modello hangs in the corridor of the museum. The original hangs on the south side of the sanctuary.

While the posture and gestures of some of the painting’s figures might suggest that this scene depicts ‘the crucifixion of Andrew’ – as the painting has often mistakenly been called – this image in fact depicts Andrew’s death, precisely at the time when he was to be released from the cross. The image originated from the Legenda Aurea, by the Dominican monk Jacobus de Varagine (1228-1298). In the Greek town of Patras, Maximilla had been willingly converted to Christianity by Andrew.

Wife to the Roman proconsul Ageas, a cruel and pagan man, Maximilla began to distance herself from Ageas, both literally and spiritually. In consequence, and completely oblivious to any criticism, her husband had Andrew crucified. While tied to the cross, Andrew kept on preaching tirelessly to the growing crowd for two more days. Alarmed by the massive protest against his unjust ruling, the proconsul decreed that the disciple should be released from the cross.

- Left in the foreground (iconographically to the right), Maximilla is seated close to the cross. Filled with sadness about Andrew’s suffering, she looks directly at the viewer, while she wipes away her tears with a piece of cloth in her left hand. Two children lean against her, as does one of the two women in conversation, who has her arm around Maximilla’s waist in an effort to comfort her.

- The crowd that has come to listen to Andrew preaching from the cross gather around both cross and executioners, and cry their support to the latter , who are freeing Andrew from the cross.

- In the foreground (ichnographically to the left), proconsul Ageas is seated on a grey horse. His extended right arm does not allude to his initial command, to crucify Andrew, but instead refers to his second command, to undo Andrew’s martyrdom. The standard with the Roman eagle emphasizes Ageas’s authority.

- Instead of erecting the cross, the soldiers and executioners carry out the proconsul’s new command. Raising his lance, the armoured soldier to the left is about to cut loose the rope at Andrew’s right hand, as does the executioner in blue loincloth with the ropes at the saint’s left foot. A soldier and two servants hope to pull down the cross.

- About to succumb yet looking forward to his full encounter with God, Andrew lifts his eyes to heaven. High on the cross, raised above the human mass, the saint already appears to partake in his mediating role between God and humanity. As legend has it, Andrew answers that God is expecting him, and then dies, surrounded by heavenly light – just before the soldiers cut the ropes.

- Heavenly light, a sign of divine assistance, surrounds the white incarnate of Andrew’s body. The anticipation of heavenly joy seemingly makes Andrew forget the pain of martyrdom. The martyr’s delight and surrender in seeing the heavenly light is in stark contrast to the bystanders below, who have been overly preoccupied with earthly torture.

- Three angels, one with a palm and two with a laurel wreath (a laurel crown and a red-and-white flower garland), symbolically offer Andrew the heavenly reward. Thwarting the soldier in armour carrying the lance, a fourth angel even ensures that Andrew won’t be denied the honour of martyrdom! The saint’s exaltation in heavenly glory was a typical motif of the Counter-Reformation, which strongly promoted the cult of saints. By emphasizing how the saints suffered to bear witness of their faith, these were put forward as vigorous examples of ‘good works’, the importance of which was denied by Lutherans and Calvinists. As such, the cross – that instrument of torture occupying almost two thirds of the entire painting – here appears as a trophy prefiguring victory.

In the background to the right, a round small temple can be seen, with a statue of the idol worshipped there. Left in the background, a gatehouse is topped by two Roman cuirasses with lances. Below right, a small dog frolics happily.

This work is on the altar of the Rubens Chapel.

This work is on the altar of the Rubens Chapel.

This painting was once commissioned to Rubens, but for some unknown reason was never delivered to his patron. Presumably it is a votive painting, which the unknown bishop ordered to express his devotion to Mary. Thus Pieter Pauwel could give it a new purpose, which he only did on his deathbed in the new prospect of his own burial chapel. In Romanticism, this was wrongly interpreted as if Rubens had designed this work as his personal memorial piece, and people were tempted to identify as many characters as possible in the painting as members of Rubens’s family, including the master. In any case, Rubens’ choice of this painting expresses his personal devotion to the Virgin.

At the time of Rubens’ death, the abbot of Saint Germain in Harelbeke profoundly testified: “He left us to see the original of several beautiful paintings he had left us”. In that case, this painting already gives us a pleasant glimpse of that heavenly original…

Mary (Ma) is sitting on a marble bench in front of a portico covered with foliage, while she is crowned by several cherubs with a garland of flowers. She herself functions as a throne for her Son. The roguish Jesus Child (JC) on her lap looks up smilingly at his mother and playfully stretches out his hands to the unknown bishop (B), who kneels down.

Behind him stands Mary Magdalene (MM), recognisable by the loose hair, the bare chest and shoulder, and the balsam jar in her hand. She is accompanied by 2 holy women.

On the far left, Saint George (G), in full armour and with a red banner in his hand, approaches triumphantly, with the speared carcass of the vanquished dragon at his feet.

On the right, the ascetic church father Saint Jerome (H), dressed only with a cardinal red drapery around the loins, kneels on his attributed lion. With difficulty, supported by a frisky angel, he holds a heavy bundle of folios in his lap: the ‘Vulgate’, i.e. the Bible that he translated into the Latin vernacular. In his raised right arm, he unfolds a banderole. Looking back, he seeks eye contact with the viewer, hoping to draw you into the intimacy of this ‘conversation with the saints’.

In the 19th century, a copy was made by the Antwerp artist Niklaas Delin. During the World War, this was used instead of the original: one could not be too careful or too cunning!

This work is on the Altar of Sacraments.

This work is on the Altar of Sacraments.

Around 1609, the Dominicans ordered this altarpiece and the two predella pieces Moses and Aaron from P.P. Rubens. On the occasion of the new choir stalls with two side altars, the Baroque altar of the Sacrament was built by Peter I Verbruggen in 1654-56. For aesthetic (and other?) reasons, the new altar was conceived – according to the contract – as a pendant to the opposing altar of the Virgin Mary, which had been begun four years earlier. In order to fit neatly into this porch altar, Rubens’ panel is enlarged in 1680, especially at the top and bottom, but also slightly in width (to 377 x 246 cm),

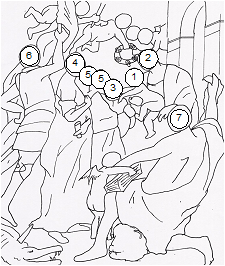

In 1616 the painting is called The Reality of the Blessed Sacrament, in other words: The real presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. The Italian term ‘dispute’, by which this painting is known, is not so much to be understood here as a discussion in the event of a difference of opinion, but as a meeting of like-minded Catholics who are looking for arguments to substantiate this belief about the Eucharist. That it is not about a pious adoration of the Sacrament either, but about an intellectual dialogue, characteristic of the scholastic tradition, is made clear by the gesticulations of authoritative scholars and church ministers: “fingers are raised, pointing, emphasising, refuting and summing up the arguments”. The Mannerist, somewhat exaggerated figures are typical of Rubens’ early period.

God the Father (∞), in heavenly soft colours of white, pink and yellow, and the symbolical dove of the Holy Spirit in the upper register underline Jesus’ real presence in the consecrated host.

Frolicsome angels (E) hold open the books of the Bible on phrases from the New Testament that form the foundation for the reality of Jesus’ presence in the Eucharist, but so that the spectator can read the text from a great distance, only one syllable per line is usually depicted.

Far left: “Caro mea vere est cibus, et sanguis meus vere [est] pot[us]” (= John 6:56; my flesh is real food and my blood is real drink). In the centre left and right this is almost repeated: “Hoc est corpus meum, quod pro vobis datur” (Lk 22:19: This is my body, which is given for you). And on the far right: “accipite et comedite: hoc est corpus meum” (Mt 26:26-27: Take and eat, this is My body).

Moreover, Rubens accentuates this point of faith through the construction and the colours. The lozenge-shaped composition is intended to create a field of tension around the white host, which, encased in a Gothic cylindrical monstrance, is not only iconographically the centre of attention, but was also originally, before the enlargement of the panel in 1680, formally the focal point.

The supernatural dimension in the tangible Blessed Sacrament is emphasised by the white host contrasting with the heavenly, blue middle field.

That blue is flanked in the colour composition by the two figures in the foreground: on the left in a golden cope, on the right in cardinal’s red. In this way the sequence of the main colours is neatly triangulated.

At the time of the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Church wanted to substantiate its view of the Eucharist against the Protestants by appealing to authoritative theologians from the, unsuspected, first centuries of Christianity. Therefore, the four great Western Church Fathers come to the fore. The two bishops, with a golden damask choir dressing gown, on the left, are Ambrose (Am), in front, as the eldest, who turns his head to the second, his pupil Augustine (Au) behind him. On the right, as their full counterpart, are a cardinal, possibly Hieronymus, in a thoughtful pose, and a monk in black Benedictine habit, possibly Pope Gregory I the Great (G?), who was first a monastery founder and abbot. But if there is an old holy man half-naked (H?), then it is St Jerome as a penitent in the desert, who, however, always has a cardinal’s red cloak with him. In that case the cardinal on the right would be the learned Saint Bonaventure. Can the black-haired man behind Ambrose be identified with John the Baptist, who in the desert was not at all concerned about a fine appearance and referred to Christ as the “Lamb of God” (the preeminent address of Jesus, as present in the host of the communion? Behind the half-naked man, the man with the elongated bald head, thoughtfully pulls on his beard and takes notes; he looks a lot like Saint Paul (P). In that case, his writing refers to the oldest exposition of the Last Supper and to the oldest formulation of the Eucharist, namely in his First Letter to the Corinthians (11:23-39). The pope, with the golden tiara, is Urban IV (U), who, through the agency of the Liège beguine, St Juliana of Cornillon (), behind him, instituted the feast of the Blessed Sacrament in 1264: ‘Corpus Christi’. He is engaged in a conversation with the great Dominican theologian Thomas Aquinas (T), who can be recognised by the golden bead on his chest. Among the other clergymen in different habit, there is another Dominican. The beardless young man in toga, dressed in red, is John the Evangelist. His two neighbours are probably also evangelists.

In 1794, the French Revolutionaries took Rubens’s painting to Paris as war booty. In 1815, the altarpiece returned to Antwerp, in 1816 to its original location.

Su questo sito web si possono scoprire altre opere di Gilles Alonso.