The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

The chapels at the ambulatory

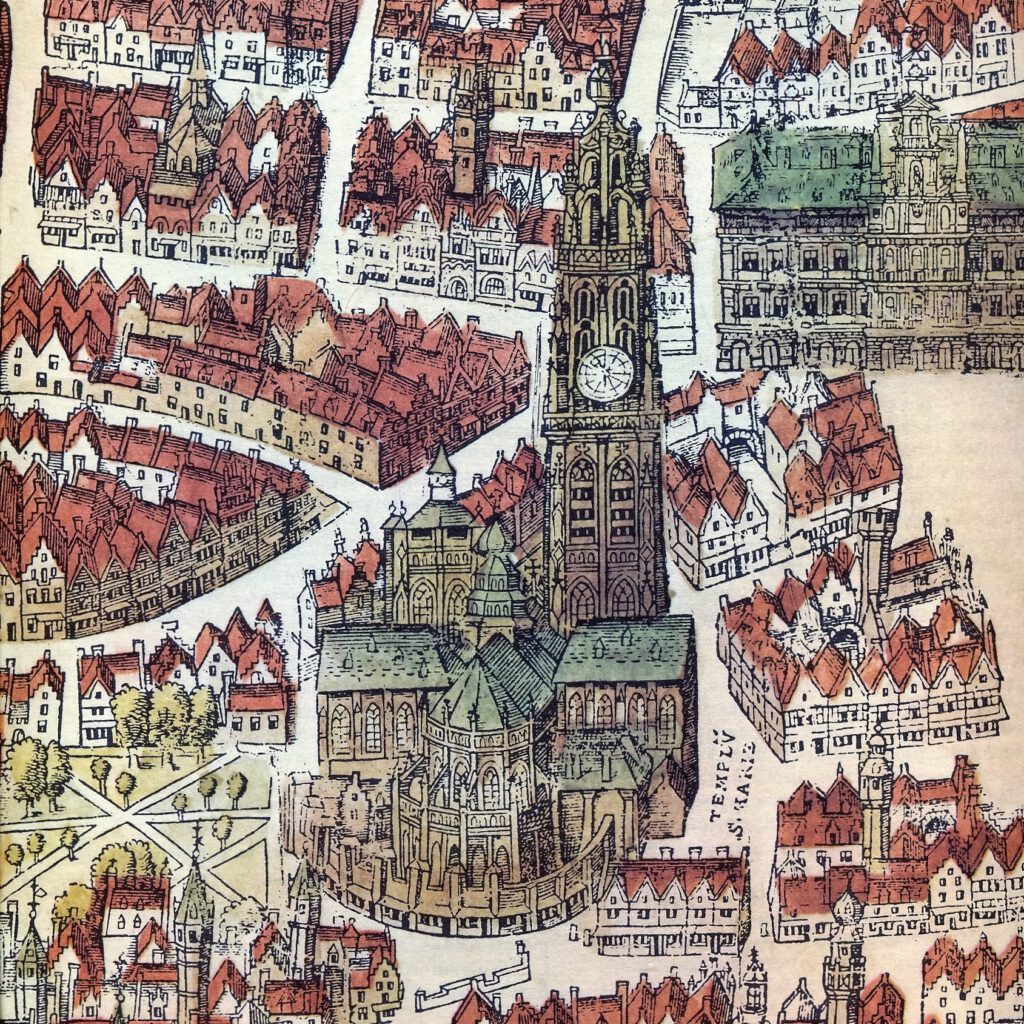

The five radiating and the six choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. chapels around the ambulatoryProcessional way around the chancel, to which choir chapels and radiating chapels, if any, give way. are part of the first phase of the construction of the Gothic church, which was started in about 1351. The first corbels were put at the two mother pillars: at the southern ambulatory a man’s face and Samson and the lion, at the northern one a man’s face amidst foliage. On the keystones of a few chapels, and especially of the ambulatory there are prophets, which can be dated between 1387 and 1391. Neither their number, nor their location or the text on the banderol that has gone gone missing, make it possible to identify them as some of the four Major Prophets or the twelve Minor ones. In the choir the oldest remaining retablePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. fragment was excavated, a stone Calvary (end 14th century).

When this new part was completely brought into use in ca. 1413 – with the Romanesque naveThe rear part of the church which is reserved for the congregation. The nave extends to the transept. still standing – it was understandably the more important groups who succeeded in obtaining a stand here. Among the strictly religious brotherhoods this was first of all the Circumcision Guild, which, exactly because of its exceptional relicA remnant of the body of a saint or a (part of) an object that has been in contact with a saint, Jesus, or Mary. The very first sanctuaries were built on graves of saints. Remnants of these saints were distributed to other churches and chapels. The first altars were usually the sarcophagi of the saints. Hence the custom of placing relics under the altar stone. Relics are also kept in shrines, and sometimes displayed in reliquaries. later moved to the more spacious chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

, which gives out to the northern transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right. (the present SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Antony’s Chapel). Further the oldest city guards were to be found there such as the Old Crossbow (in the present Saint Vincent’s Chapel), the Old Longbow (in the present Louis Frarijn’s Chapel, later in the present Lamentation Chapel) and the Young Longbow in Saint Barbara’s Chapel.

The decoration was dictated by fashion. Typical of the first half of the 16th century were mural paintings with a red background, with on it the so-called ‘pressed brocade’, a decorative relief with a base of wax. The incidence of light, the foundation of Gothic church architecture, was more and more hidden from view because the altars became gradually higher: in the 16th century, certainly after 1585, by the wide, painted triptychs, in the 17th century by the high Baroque portico altars.

After having been looted by the French revolutionaries the dozen of chapels presented a cheerless prospect, until the middle of the 19th century, when they received a new specific use as devotional chapels. This was the onset of a totally new design in neo-Gothic style, which as far as the wall and ceiling decoration were concerned, went back to older traces of decoration, as far as possible. In this way the former users of these spaces were honoured, which was part of the nationalist feelings of those days. For long Catholics dreamt of a revival of the guild system in a Christian way, but 19th century social economic reality did not allow this any longer. The tangible consequence was that professional associations no longer desired a devotional space of their own, not even their former chapels. The only initiative in this direction, this of Saint Luke’s Guild, failed quite soon and could only be brought to a ‘good’ end thanks to the private initiative of a vicarAccording to Canon Law, a vicar is a substitute of a minister. In a diocese, several vicars assist a bishop: priests who look after a certain policy area within the diocese (parishes, liturgy, etc.). who celebrated his jubilee. A burial chapel in the strict sense, was made impossible by law. This is why some families wanted to be remembered by a complete series of stained glass windows in one and the same chapel. Some chapels received a devotional purpose on the occasion of a patronage appointment – Saint Joseph as the patron of the Catholic Church in 1870, Saint Vincent de Paul as the patron of charity in 1885 – or a beatification or canonization – BlessedUsed of a person who has been beatified. Beatification precedes canonisation and means likewise that the Church recognises that this deceased person has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. Like a saint, he/she may be venerated (not worshipped). Some beatified people are never canonised, usually because they have only a local significance. Louis Fraryn in 1868 and Saint John Berchmans in 1888.

In the turbulent 1960’s the austere, modernist style got a hold over churches because of the renewal of the Second Vatican CouncilA large meeting of ecclesiastical office holders, mainly bishops, presided by the pope, to make decisions concerning faith, church customs, etc. A council is usually named after the place where it was held. Examples: the Council of Trent [1645-1653] and the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965], which is also the last council for the time being., and triumphalist neo-Gothic with its colourful fringes fell into disgrace. The ambulatory and its chapels could only just avoid another iconoclasm. After the 1998-2004 restoration the chapels and the ambulatory shine again in their full 19th century glory. Some dream of giving these spaces an appropriate interpretation in line with Christian values as they are lived today.

Before Circumcision or Jerusalem Chapel

A small church that is not a parish church. It may be part of a larger entity such as a hospital, school, or an alms-house, or it may stand alone.

An enclosed part of a church with its own altar.

,

also the municipality’s Chapel of the Adoration of the Magi

After the northern transeptThe transept forms, as it were, the crossbeam of the cruciform floor plan. The transept consists of two semi transepts, each of which protrudes from the nave on the left and right. had been finished this adjacent chapel was built from 1494 till 1499: an extra space that blurs the original idea of a cruciform floor plan. The space is also unusually large as it was meant for the city councilA large meeting of ecclesiastical office holders, mainly bishops, presided by the pope, to make decisions concerning faith, church customs, etc. A council is usually named after the place where it was held. Examples: the Council of Trent [1645-1653] and the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965], which is also the last council for the time being., which shared the prestige of this chapel with pilgrims that had returned from the Holy Land, the ‘Jerusalem Knights’. Because the brick vaultings showed quite a few irregularities they were overpainted with a clean brick imitation.

The importance of the harbour showed as far as the municipality’s chapel. In Antwerp the English Company of Merchant Adventurers warranted the import of semi-manufactured woollen cloth to have it perfected by the cloth shearers. Here their members were privileged with jurisdiction of their own and exemption of beer and wine excises. Within a stone’s throw of this chapel the town gave them a premises, which they extended to a partly covered market: the ‘English premises’. It is not a co-incidence that the first stock exchange was founded in their neighbourhood. As a consequence the then Wolstraat [Wool Street] was popularly called ‘Engelandstraat’ [England Street] and it got its present name, ‘Oude Beurs’ (Ancient Stock Exchange) in 1531. The Merchants were royally protected by Henry VII. The two 1503 stained glass windows remind of the Intercursus Magnus, the important commercial treaty that the Burgundian and English sovereigns concluded in 1496. The Merchant Adventurers suspended it and moved to Bergen-op-Zoom, but in 1502 the Antwerp city council could entice them with new privileges and this was the direct occasion to have these windows installed.

Each of the two parties has been immortalized in a stained glass window, with on each the royal couple assisted by their name saintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. (except for Henry VII of England). They are typified by their blazons, their mottos and their crowned initials linked up by lovers’ knots.

On the Burgundian window, which is the left one, are Philip the Handsome and Joanna I of Castile (‘the Madwoman’). Above them their kingdom is represented by the patron saints: Andrew for Burgundy and James for Spain.

On the right there is the English window, with king Henry VII of Lancaster and queen Elizabeth of York, respectively patronized by the patron of England, Saint George, and the proper name saint, the generous Elizabeth of Hungary. Also two holy kings of England have been represented – in the form of statues in niches. Directly behind the king there is ‘Saint’ Henry VI, and behind the queen there is Saint Edward the Confessor. By the marriage of this royal couple the horrible War of the Roses between the two royal houses came to an end and the dynasty of the Tudors was founded. It would be logical if the framing alluded to this by alternating the two symbols of the new dynasty: the red white Tudor rose and the Tudor harrow. In the course of the 19th century restoration however by mistake the red white Tudor rose was replaced by the red Lancaster rose. At the bottom there is the coat of arms of the Merchants with two leaping up horses as armour bearers.

But from the very beginning this chapel was actually destined as a worthy accommodation for the city relicA remnant of the body of a saint or a (part of) an object that has been in contact with a saint, Jesus, or Mary. The very first sanctuaries were built on graves of saints. Remnants of these saints were distributed to other churches and chapels. The first altars were usually the sarcophagi of the saints. Hence the custom of placing relics under the altar stone. Relics are also kept in shrines, and sometimes displayed in reliquaries., which was brought here only in 1513. Now it is hard to believe, but the medieval Antwerpians believed they possessed one of the most important relics in Christianity: Jesus’s foreskin (preputium Domini). In accordance with the Jewish law the Messiah was circumcised on the eighth day of his life, was He not? The legend went that the precious valuable was a gift from the margrave of Antwerp, Godfrey of Bouillon, the famous crusader, who in 1099 accepted the title ‘Protector of the Holy Grave’ in Jerusalem, and who would also have given the ‘Holy Blood’ as a present to Bruges. Not by co-incidence the alleged circumcision relic, which was a symbol of Catholicism with its commercialized devotions, got lost in the turbulent period of the 1566 Iconoclasms.

After the restoration of Catholic worship in 1585, the chapel was devoted to the Holy Three Kings. In the same way as the three Magi in the group of statues above the altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine. knelt down to present their offerings to the Infant Jesus, the members of the town council came to offer three heavy wax candles here on the feast of EpiphanyOn January 6 the gospel story is commemorated which tells how magi from the East came to honour Jesus as the Son of God. This feast is also called Epiphany (from the Greek word referring to the manifestation of a deity), because the magi acknowledge Jesus as the Son of God who has become man.. This devotion may explain the choice for the theme Rubens was asked to work out for the States Room in the Antwerp City Hall at the occasion of the negotiations for the Twelve Years’ Truce in 1609: The adoration of the Magi (Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado).

Although the relic had disappeared, the place of worship kept being called ‘Circumcision Chapel’. Since 1590 the altar was adorned with The Lamentation of Christ, the subdued dramatic masterpiece by Quentin Matsys (1509-1511), which the municipality had bought from the cabinet makers’ guild in 1577, at the recommendation of Maarten de Vos, so that it would not vanish from Antwerp. Until the placing of Rubens’s Descent from the Cross this monumental triptych was known as the most worth seeing work of art in the cathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is., as shows in an Austrian travel account from 1606. After 1798 this extraordinary work of art ended up in the KMSKA (Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp) via the museum of the Academy. Even in the 17th century people were glad to be reminded of this relic with the colourful stained glass windows at the eastern side of the northern transept: next to Jesus’s circumcision (1615), the donator Godfrey of Bouillon is shown here as the founder of Saint Michael’s ChapterAll the canons attached to a cathedral or other important church, which is then called a collegiate church. In religious orders, this is also the meeting of the religious, in a chapter house, with participants having ‘a voice in the chapter’. (1616).

In 1806 the elegant Baroque devotional statue of Saint Antony of Padua (Artus II Quiellinus, second half 17th century) from the abolished Friar Minor conventComplex of buildings in which members of a religious order live together. They follow the rule of their founder. The oldest monastic orders are the Carthusians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians [and their female counterparts]. Note: Benedictines, Premonstratensians, and Cistercians [and their female counterparts] live in abbeys; Jesuits in houses. was entrusted to the main church. The devotion for this saint, whose popularity fiercely increased in the 19th century, has been located in this spacious chapel. The book in his hand first of all stands for the gospelOne of the four books of the Bible that focus on Jesus’s actions and sayings, his death and resurrection. The four evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. ‘Gospel’ is the Old English translation of the Greek evangeleon, which literally means ‘Good News’. This term refers to the core message of these books., which was the inspiration of his life. It also recalls the story of a stolen textbook that was brought back to the saint anonymously, which was the occasion to make him patron saint of lost objects.

Formerly devoted to Saint Antony Abbott

and to Saint Hubert of the hunters

From the very beginning the Guild of Saint Antony Abbott was located here, and they shared the chapel with the Saint Hubert hunters’ guild from ca. 1587 till 1797. In 1594 Maarten de Vos painted the popular theme The temptations of Saint Antony (Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp) for their altar. The tempting phantasies which in the form of extravagant demons, half animal, half human, do not release the Egyptian hermitA person who lives alone and isolated from the world in order to live a sober and pious life. The home of a hermit is called “hermitage”. (251-356) and carry him through the air, have no doubt caught the attention of the spectator – hopefully with an edifying effect. On the late Gothic 15th century keystone this theme has been pithily worked out: two devils menace the very old Antony.

It is very exceptional that the pair of silver ampullas of both guilds, a high Baroque creation by Norbert Lesteens (1669), has been preserved. On the wine ampulla two angels press grapes, on the water ampulla swimming angels catch a sea serpent. Even the ampulla’s ears have been thematically decorated! Just like on the altar triptych, on the border of the embossed dish that goes with them, of the two saints most attention is given to Saint Antony.

Even more exceptional is the way in which the late Gothic reliquaryContainer for relics. Often this is a philatory: a decorated glass holder on a pedestal, in which a relic can be placed for veneration. It is important to know that relics cannot be worshipped, only venerated. horn of Saint Hubert (ca. 1525) could survive so many troubles. In about 1820 it was taken to Saint Charles Borromeo’s Church. In the yearly Saint Hubert’s Guild massThe liturgical celebration in which the Eucharist is central. It consists of two main parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The main parts of the Liturgy of the Word are the prayers for mercy, the Bible readings, and the homily. The Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the offertory, whereby bread and wine are placed on the altar. This is followed by the Eucharistic Prayer, during which the praise of God is sung, and the consecration takes place. Fixed elements are also the praying of the Our Father and a wish for peace, and so one can symbolically sit down at the table with Jesus during Communion. Mass ends with a mission (the Latin missa, from which ‘Mass’ has been derived): the instruction to go out into the world in the same spirit. worshippers still come to venerate the relic there and in this way it has kept its mediating role in the relation of the worshipper with his God.

In 1888 Jan-Baptist De Boeck and Jan-Baptist Van Wint supplied the wooden neo Gothic retablePainted and/or carved back wall of an altar placed against a wall or pillar. Below the retable there is sometimes a predella. for the devotion of the Holy Heart of Mary, which was then housed in this chapel. To remind us of the former devotions, the statues of Saint Antony Abbott and Saint Hubert each crown a wing. The figure of Mary in the centre is invoked with ‘Holy Mary, refuge of sinners, pray for us’. To give evidence of her mediating role towards God, she is flanked by the Calvary and the Pieta, two scenes that represent her ‘com’-passion in the full sense of the word as taking part in Jesus’s healing suffering. On top of these we can see the two most striking scenes of conversion in the New TestamentPart of the Bible with texts from after the birth of Jesus. This volume holds 4 gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, 14 letters of Paul, 7 apostolic letters and the Book of Revelation (or Apocalypse).: Mary Magdalen’s (Lk. 7:36-50) and Paul’s (Acts 9:4). On the wings there are 16 saints who arose from a sinful life through their faith in Jesus Christ and their devotion for Mary.

Formerly Saint George’s of the Old Crossbow

the two Saints John of the cabinetmakers

The keystone, end 14th or beginning 15th century, indicates that from the very beginning the oldest of the six Antwerp armed guilds, the Old Crossbow Guild, founded in 1306, had a chapel at their disposal in the oldest part of the new, Gothic church This chapel was devoted to Saint George. This brave patron saint, with a shield and a sword, is standing on the dragon that he has just laid low. Notice the peculiar detail of the dragon’s tail that has playfully coiled around the tree trunk. Already before this the guild had a chapel near the shooting range, in the Southern part of the city, which was the origin of Saint George’s church.

The vault painting, which proudly shows the emblem of the crossbow and the guild’s heraldic arms, has been dated ‘1566’, but it was completely restored in 1898. The emblems in the wall decorations also testify of 19th century interest in proper history.

In 1590 the cabinetmakers took the place of the Old Crossbow, after this guild had moved to the transept. The cabinetmakers did not leave any trace on the spot, but fortunately their Baroque altar triptych by Hendrik van Balen from 1622 has still been preserved.

In 1895 family members wanted to commemorate their deceased sister, who had devoted her whole life to charitable works. This is why the chapel was devoted to Saint Vincent de Paul (1581-1660), paragon of Christian charity. Since the 1840’s this French saint was made widely known in Belgium by the charitable activities of Saint Vincent de Paul’s societies in many parishes. Since 1856 the seat of the Saint Vincent’s Society of the Antwerp district was in Kammenstraat, where now the centre of Sint-Egidiusgemeenschap (Saint Giles Community) is.

Sculptor Jan Baptist van Wint carved the central part of the retable (1898), which has been constructed around the statue of ‘Monsieur Vincent’, who can be recognized well by his physiognomy with his fringe of beard and sharp nose, the priest’s cassockA long, usually black, garment that reaches down to the feet and is closed at the front from bottom to top with small buttons. Synonym: soutane. and the calotte. The naked child on his arm represents the work of clothing the naked. Around this group of statues the other Works of Charity have been elaborated with Vincent as the main character: on the left, freeing the prisoners and below it burying the dead, on the right visiting the sick and underneath harbouring the strangers. On the predellaThe base of an altarpiece. Like the altarpiece, the predella may be painted or sculpted. below are the works that are mentioned most: feeding the hungry and quenching the thirsty. Vincent is assisted by members of the congregations he has founded: on the one hand the brothers Lazarites, on the other the Daughters of Charity, the popular sisters with the wide wimples or cornettes, which accounts for their nickname ‘flying nuns’. These sisters were also active in Antwerp, such as in Saint Vincent’s hospital since 1875. On the painted wings of the predella (Jan Antony, 1897) seven angels mention the seven Works of Charity on banderols. The choice for the saints on the wings (also by Jan Antony, 1897), was partly inspired by their charitable commitment, partly by the name saints of the deceased person.

Of all parishioners the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul undoubtedly had the most intense bond with the devotion of this altarpiece. In the 20th century these sisters ran the parochial girls’ domestic science school in Reyndersstraat and engaged in home nursing from their house in Heilige Geeststraat, which was behind the school.

Ever again the ‘Works of Charity’ (Mth. 25:31-46) have been the inspiring guideline for Christians to dedicate themselves to their destitute fellow men, each time in different social circumstances. Today, in a time when parish borders fade away, there are other initiatives of social relief, such as De Loodsen, het Werk der Daklozen (for the homeless) and Sint-Egidiusgemeenschap (Saint Giles Community), that take up these tasks.

Formerly chapter room, Saint Ursula’s chapel

In the 14th century the first bayThe space between two supports (wall or pillars) in the longitudinal direction of the nave, transept, choir, or aisle. of the present Saint Joseph’s chapel that gives out onto the ambulatoryProcessional way around the chancel, to which choir chapels and radiating chapels, if any, give way. was a separate longitudinal chapel. To the north a wall partitioned it off from the Gothic chapter room, which then took the two northern bays of the present chapel. To assemble (day)light was needed, but when the Circumcision chapel was built, the windows in the western wall were bricked up.

The original devotion in the old longitudinal chapel cannot be detected anymore, but one can imagine how the canons passed by here when they went to the chapter room coming from the sanctuary. It is not impossible that the keystone Moses with the ‘two tables of the law’ (The Ten Commandments) is connected with the chapter meetings, where texts of ecclesiastic law are directive.

Once the meeting hall had been transferred to the southern side of the ambulatory the former chapter room was established as a chapel in honour of Saint Ursula. The costs for this were fully borne by the passionate canonSomeone who, together with other canons, is attached to a cathedral or collegiate church and whose main task is to ensure choral prayer. Gaspar Van den Cruyce, who had brought relics of this martyrSomeone who refused to renounce his/her faith and was therefore killed. Many martyrs are also saints. from Cologne. Just before the chapel was consecratedIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words. in 1593, the forty-year-old, but physically weak, canon died and was buried in front of the altar, which is, exceptionally, against the northern wall. In the same year his family had the chapel enlarged by having the northern wall of the adjacent chapel pulled down. Across the entire space a grisaille wall painting (1593) has been repeated. In the two friezes there is a simple cross as family arms [Cruyce = ‘kruis’ = cross]. The whole is made up of elaborate grotesques consisting of birds, a couple of dogs and angels with a lute. Also the pillars of the adjacent bay in the ambulatory were made part of this decoration. The anonymous altar triptych with a Calvary called as it were the name of the canon, who has been depicted on the left inner wing (iconographically right). On the right wing is Saint Ursula, while the name saint of the benefactor is on the outer wings, which together form The Adoration of the Magi. In 1798 the triptych was sold but in the beginning of the 19th century it was given back to the church. Now it is in the northern ambulatory near the chapel. Immediately after pope Pius IX had proclaimed Saint Joseph patron of the Church during the First Vatican Council in 1870, it was decided to devote this old chapel to Jesus’s foster fatherPriest who is a member of a religious order. and two years later the nearly completely renewed space was consecrated. In the central niche of the retable, carved by Jan-Baptist De Boeck and Jan-Baptist Van Wint in 1871, is the statue of Saint Joseph with the infant Jesus on his arm.

Around it seven polychrome tableaus evoke scenes from his life. The most eye-striking one is this in which young Jesus is learning his foster father’s craft: Jesus, on his knees, is holding a pair of compasses and is looking up at Joseph, who is planing boards at his bench. While behind Joseph there is a rack with carpenter’s tools, there is a meaningful shelf with books behind Mary. After all the lady of the house stands for the more intellectual and contemplative, and also the educational work: she is praying from a book, which does not prevent her from watching her growing child.

The painted wings by Louis Hendrickx (1873) draw the attention by their astonishing details and the warm hues of textiles. In the upper sections they illustrate the patronage of Saint Joseph: on the left (iconographically right) pope Pius proclaims him patron of the Church, on the right king Charles II of Spain dedicates the Southern Low Countries to him in 1679.

In 1870 it was discovered that a rose window had been walled up. In that same year this gave rise to a conspicuous stained glass window by August Stalins and Alfons Janssens, after a design by Louis Hendrickx: The tree of Jesse, in which Joseph’s descent is traced to Christ’s most important ancestors and climbs up to king David. Distant relatives of canon Van den Cruyce donated the stained glass windows Saints Julius and Victoria (1872) and Saints Ursula and Gaspar (1873). The bright colours from the Paris workshop Edouard Didron darken the chapel, which from the very beginning gave rise to quite some criticism.

of the artists

The attribute of the saint bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’. on the keystone is so vague that we cannot identify him. And so we can only guess the oldest destination of this chapel.

The Antwerp association of painters and other artists, founded in 1382 and certainly since 1454 known as Saint Luke’s Guild, was possibly the first guild to have received a complete chapel of their own. Later this honour however was claimed by the linen weavers. Apart from this, Saint Luke’s chapel is the only of the chapels around the ambulatory that has kept its original function.

Because Saint Luke’s Guild collided with the headstrong nature of their deanPriest – usually a parish priest himself – who coordinates the work of several neighbouring parishes [a deanery]., Adam van Noort, the commission for the definitive altar piece, Saint Luke portrays Mary and Child, was given to one of their most renowned members: Maarten de Vos. For him this 1602 realisation was probably one of the most glorious in his long career, since this altar piece was representative of the artists’ guild. The scene, which is situated in a palace rather than in a painter’s workshop, shows the technical as well as the intellectual aspects of the craft. De Vos also finished the predella panels but due to his death in 1603 the execution of the wings had to be left to Otto van Veen and Ambrose Francken. The adoption to the fashionable portico altar in ca. 1754 caused the panels to be dispersed, but thanks to the French confiscation they were reunited and finally ended up in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1648-1649 the stained glass windows were renewed. The guild’s dean, the famous printer Balthasar Moretus, paid for the central window with the coat of arms of the guild. The deans of the glaziers donated the two side windows.

In Baroque times there used to be five candleholders (Peter I Verbrugghen, 1657-1658) on the balustrade. They took the form of angels, each representing one of the important forms of art in the guild: painting, sculpting, building, poetry and printing. Unfortunately this original work of art got lost during the French Revolutionary Rule.

Only a few artists found a final resting-place in the chapel of their guild: beside Maarten de Vos, among others engraver ‘carver’ Philip Galle ( 1612), painter Cornelis de Vos ( 1651) and sculptor Peter I Verbrugghen ( 1686). Their tombstones however have gone missing.

Saint Luke’s Guild was abolished in 1795 and refounded in 1808. In 1854 it celebrated its official 400 year jubilee with a gigantic ‘Landjuweel’ (a festive theatre contest with a tradition that goes back to the Middle Ages). At this occasion a new altar was consecrated in its old chapel. This was the only realisation of the special committee ‘to re-establish the altar of Saint Luke’s Guild in the former cathedral church of Antwerp’. Apparently the revenues of the exhibition of ancient paintings in the Province House (the present Bishop’s House) in the next year, did not provide for the dynamism and finances needed.

So they had to wait until 1892, when again the stained-glass artists installed a present in kind. Saint Luke’s chapel, the only chapel of the ambulatory that had not been redecorated yet, gave the stained-glass workshop Stalins-Janssens the opportunity to immortalize themselves with a stained-glass window of their own in the cathedral, at the occasion of their 25th anniversary, four years before. This explains why Saint Augustine and Saint Alphonsus Maria de’ Liguori, the name saints of the two stained-glass artists, flank Luke. Even though the score of the angel top right may seem very realistic at close quarters, it is pure phantasy, no composition. The same workshop also made the two side windows with name saints but the churchwardens asked for the use of monochrome grisaille colours so as not to make the chapel too dark. The left one commemorates Carolus Ludovicus Borre and Carolina Julia Smekens, the right one was made on the initiative of Emile Dumont for deceased members of his family.

When in 1893 also Mgr. PetrusHe was one of the twelve apostles. He was a fisherman who, together with his brother Andrew, was called by Jesus to follow Him. He is the disciple most often mentioned In the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. His original name was Simon. He got his nickname Peter (i.e. rock) from Jesus, who, according to tradition, said that He would build His Church on this rock. Josephus Franciscus Sacre celebrated his 25th anniversary as a parish priestA priest in charge of a parish. and dean, he had an altar built in honour of Saint Luke, financed with the gifts from worshippers of the deanery. For this industrious priestIn the Roman Catholic Church, the priest is an unmarried man ordained as a priest by the bishop, which gives him the right to administer the six other sacraments: baptism, confirmation, confession, Eucharist, marriage, and the anointing of the sick. this was more than merely looking back nostalgically at a glorious past, but it was a symbolic onset to follow the footsteps of the guilds of olden years and to work hard for the foundation of the Verbond der Christene Vakverenigingen van Antwerpen en Omstreken (Society of Christian Unions of Antwerp and Environs), the present Beweging.net. The whole decoration of the chapel was designed and lead by architect Frans Baeckelmans from 1892 till 1894.

The retable (Albrecht de Vriendt, 1893) has been worked out symmetrically and breathes the atmosphere of pious romanticism. The traditional theme of Saint Luke portraying Our Lady and Child has been widened into Mary is honoured by the arts. Mary is sitting on an impressive neo-Romanesque throne amidst a closed blooming garden with apple blossom and many kinds of flowers such as lilies, roses, poppies. The ‘garden locked’ has been borrowed from the Song of Songs (4:12) and serves as an allegory for Mary’s Immaculate Conception. With the old city device ‘Furtunata Antverpia’ on the back of the throne Antwerp considers itself fortunate with Mary as the patron of the city. As a consequence the Antwerpians honour her with arts. Our Lady’s Cathedral in the background on the right does not only represent the church of the person celebrating his jubilee, but also architecture that reveres Mary. Angels singing and playing the violin praise with music. The coat of arms of Saint Luke’s Guild and of Chamber of Rhetoric ‘de Violieren’, which flank the throne, stand for the plastic, and literary and musical sections within the guild.

On the left panel, in the interior of his church, the praying and kneeling Mgr. Sacre, who is celebrating his anniversary, is backed by Saint Joseph and further on the left wing are the two other name saints: Francis of Assisi and the apostleThis is the name given to the principal twelve disciples of Jesus, who were sent by Him to preach the gospel. By extension, the term is also used for other preachers, such as the Apostle Paul and Father Damien (“The Apostle of the Lepers”). Peter. On the other wing Thomas Aquinas and Jerome typify the Monsignor as a man of theological studies.

A year later the wall and vault paintings by Jan Baetens were made. The reconstruction painting on the vaulting is an interpretation of the angels that used to be there originally. At the top of the side walls are the coats of arms of Antwerp patrons and artists. At the bottom of the eastern wall, against a red background, in the large coat of arms of Saint Luke’s Guild, the three empty, still to be coloured shields explain the Dutch verb schilderen (to paint; schild = shield). Underneath the bouquet of yellow flowers (‘violets’) refer to the Chamber of Rhetoric de Violieren, which joined the guild in 1480. The umbrella Saint Luke’s Guild took over its literary motto: ‘Uut jonsten versaemt’ (‘joined by fondness’ or ‘gathered by fondness’). Since then this motto has been referring to all crafts that were united by the guild. As a last detail you may notice how blue tiles on the floor alternate with white ones carrying the neo-Gothic initials ‘SL’.

Formerly Saint Thomas of the furriers

On the keystone a prophet with a turban, in bust, is holding a banderol in both hands. In the beginning of the 16th century the craft of the furriers took over the chapel from Saint Thomas confraternity. Later the company of lamb workers was founded within the furriers’ craft. Their patron was John the Baptist, who had indicated Jesus as the Lamb of God. This is why, after the Iconoclast Fury, Maarten de Vos had to divide the space available on the retable (1574) between the two patron saints in a balanced way: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas on the central panel, and on the wings The BaptismThrough this sacrament, a person becomes a member of the Church community of faith. The core of the event is a ritual washing, which is usually limited to sprinkling the head with water. Traditionally baptism is administered by a priest, but nowadays it is often also done by a deacon. of Christ and The Decapitation of Saint John the Baptist. Via the École Centrale the triptych has ended up in the KMSKA (Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp).

Theophile Smekens was a judge, for many years he was the president of the Royal Society to Promote the Fine Arts in Antwerp and he was the co-founder of Saint Vincent’s Society in Antwerp. He asked his former fellow-student Jean-Baptiste Bethune to make stained glass windows: first to commemorate his deceased father Charles (‘Carolus’) ( 1861) and the latter’s first and second wife on the left window, later for his deceased brotherA male religious who is not a priest. Louis ( 1868) on the right one. By co-incidence these windows can be seen as pendants of the ones that Bethune had made for Saint Barbara’s chapel, on the opposite side of the ambulatory, a few years before. Finally, in 1887, Theophile Smekens commissioned stained glass windows, this time to August Stalins and Alfons Janssens, in honour of his sister Carolina Julia, his already deceased brother Emilius ( 1869) and – not the least – of himself. With his name saint Theophilus – positioned higher – in the central window, the commissioner could enjoy his ‘memorial’ for more than 30 years … until he himself closed his eyes in 1921.

The exceptional canonization of a Fleming by Pope Leo XIII in 1888 was the immediate cause to dedicate this chapel anew to the patron saint of Flemish studying youngsters. The decoration of the chapel was designed by Adolphe Kockerols and executed by architect Frans Baeckelmans. This time the Le Grelle family bore all the costs, which enabled them to link their name to the cathedral. The chapel was consecrated in 1891.

By means of the wall paintings by Jan Baetens and of the retable by Piet van der Ouderaa it is possible to go through the short life of John Berchmans. The coats of arms on the left wall indicate the municipalities where he lived; the ones on the right wall are of popes: those who were reigning during his lifetime as well as those who contributed to his canonization.

In the background of the retable a few scenes from his life are told. John is an altar boy in the main church of Diest, which, to improve the perceptibility, has been simplified into an open field chapel here. During his noviciate in Malines he is wearing the Jesuit cassock and he is teaching catechism to children in the exterior parishes. From Antwerp he sets off to Rome – on foot, via Loreto – with a few companions to continue his studies: filled with joy John kneels down when he discerns Saint Peter’s BasilicaA rectangular building consisting of a central nave with a side aisle on each side. On the short side opposite the entrance, there is a round extension, the apse, where the altar is located. The Antwerp Saint Charles Borromeo church is based on this basilica structure.

An honorary title awarded to a church because of its special significance, for example as a place of pilgrimage. There are 29 basilicas in Belgium, the best known of which are the Basilica of Scherpenheuvel and the Basilica of Koekelberg. Worldwide this is Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. These churches do not have the architectural form of a basilica.

in the distance. After his final philosophy exam he became gravely ill and he died on 13 August 1621, only 22 years old. On the day of his death many people come to pay their last respects. Blind Catarina da Recanati is healed when touching the dead body: the main theme of the central panel.

Even though the style of the painting should be seen as historic realism, the fantasized interior of a Roman loggia has nothing of the Baroque San Ignazio Church or the sacristyThe room where the priest(s), the prayer leader(s) and the altar server(s) and/or acolyte(s) prepare and change clothes for Mass. where his body was lying in state. The reflection in the candleholders strikes the imagination.

On the wings are the patron saints and the arms of Henri Le Grelle († 1872) and his distant relative Marie-Therese Julie Le Grelle († 1888), to whom he was married. However tempting for all kinds of edifying interpretations, the letters ‘A A A’ did not originally belong to the Le Grelle family, but to family related by marriage and their actual meaning has not been discovered yet.

On the predella there is Christ amidst his twelve apostles. In the once gilded reliquary above the retable there is a fragment of a garment of the saint.

Formerly Saint Martin of the wine taverners

True to tradition the easternmost radiating chapelA chapel on the curved back wall of the choir. In the symbolism of the cruciform floor plan, in which the choir stands for the head of the crucified Jesus, these chapels form, as it were, a halo around this head. This accounts for their name: ‘radiating chapels’., through which the sunlight enters the church in the morning, is linked up with ‘Christ, the Light of the world’. Here this is also emphasized by a relief on the keystone: Christ Salvator. Traditionally the chapel is devoted to Mary, who gave Christ the light of life.

For about 100 years the choirIn a church with a cruciform floor plan, the part of the church that lies on the side of the nave opposite to the transept. The main altar is in the choir. boys honoured Mary with an antiphony here every evening. Throughout the years this was the Salve Regina (Hail Queen), which was also the name of the then confraternity here. But due to the foundation of the new Guild of Our Lady’s Praise, in 1478, the homage to Mary was given more and more in the spacious Our Lady’s Chapel in the northern aisleLengthwise the nave [in exceptional cases also the transept] of the church is divided into aisles. An aisle is the space between two series of pillars or between a series of pillars and the outer wall. Each aisle is divided into bays..

From 1476 the chapel was used by the guild of the Old Longbow until 1590, when the chapter had asked them to move to the southern transept. Their place was taken by the Wine Taverners’ guild, who commissioned The Wedding at Cana to Maarten de Vos in 1597 for this chapel.

In 1866-1867 this space was refurbished as the chapel of the Lamentation of Christ, which is a synonym of the Pieta: the sculpture, ascribed to Artus II Quellinus, which has been positioned in the centre. With wide gestures and a painful look up to heaven, Mary evokes her sorrow at the lifeless body of her son. The high-Baroque wooden statue however was polychromed in a neo-Gothic way.

The three brightly coloured stained glass windows (Jean-Baptist Bethune, 1866) show Jesus’s life, with an emphasis on the Passion (left and central window) and His glorification (right window). The first scene, The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, opens the whole thematically because old Simeon alludes to Jesus as Light of the world, but also announces Mary’s suffering (Lk. 2:25-35).

The wall paintings after a design by Francois Durlet, 1861, were executed by Jan Baetens six years later, and are the oldest neo-Gothic ones in the choir chapels. They consist of emblems of former users. On the left: crossed arrows and a glove of the Old Longbow. On the right: a wine press and a bunch of grapes of the wine taverners, based on a similar wall painting from 1597. Against the side walls there are strings of thistles and passion flowers, which are symbolic of Jesus’s crown of thorns. Even the three pistils of the passion flower refer to the three nails of the cross.

As a sequel to the scene of the Pieta, there is a white stone statue by Jan Baptist De Boeck and Jan Baptist Van Wint in a niche left of the altar: Christ entombed.

Formerly Saints Crispin and Crispian of the shoemakers

It is possible that the guild of the Young Longbow had this chapel from its foundation in 1485 until it moved to the central naveThe space between the two central series of pillars of the nave. in ca. 1595. Afterwards only the one guild of tanners and shoemakers made use of it, but after they had split up in 1682 the tanners went to the chapel of the alms-house in Huidevettersstraat (Tanners Street) for their services. On the altar triptych in the cathedral this guild were all too glad to have Ambrose I Francken represent their patron saints Crispin and Crispian, who not only worked in favour of the poor and proclaimed the Christian faith, but were also themselves shoemakers by profession. The central panel, with on it their strongly embroidered tortures, was confiscated by the French occupier and finally ended up in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts. The wings, which were removed in ca. 1674 to make the central panel fit in the new Baroque portico altar, were kept in the possession of the shoemakers’ guild and after the 1802 concordat they were preserved in Saint Charles Borromeo’s Church, where the yearly guild’s mass is still celebrated.

The polychrome late Baroque statue of Saint Barbara by Jacobus II van der Neer (1826) was made on the occasion of the dedication of the chapel to this saint martyr and patron saint against sudden death. The foundation of the brotherhood in her honour in 1877 was the stimulus to have the chapel redecorated after a design by architect Frans Baeckelmans (1889-1891), which included a painted altar triptych by Jean-Baptiste Anthony (1891). The central panel tells the legend of Saint Barbara. In the middle is the young, ravishing king’s daughter, in rich clothes, with her attributes: the sword of martyrdom and the tower in which she was locked up by her father and in which she had a third window made in honour of the Triune God, core of Christian faith. In the left scene she is being taught the Christian belief by Origenes, to great anger of her father, who does not agree with her conversion. Notice that the crucifix in the hands of the Christian teacher is a true representation of the neo-Gothic triumphal crossLarge crucifix hanging in the first arch of the choir or chancel. In churches with a rood screen, the triumphal cross usually stands on this. in the cathedral. The Gothic church tower under construction in the background may be regarded as a successful and playful naturalistic representation of her most personal attribute. In the right scene the father is at the point of decapitating her personally with his sword. On the predella Christ is flanked by the four evangelists. The wings show patron saints of the Lombaerts family: on the left Saint Cornelia and Saint James, on the right Saint Joseph and Saint John the Baptist.

With the white marble memorial slab (Jozef Geefs, 1852, after a design by Francois Durlet) the Royal Society to Promote the Fine Arts in Antwerp has paid tribute to its chariman Franciscus-Antonius Verdussen ( 1850), alderman, member of parliament and since 1839 also chairman of the church board. In 1815 he was a member of the delegation that went to The Hague to advocate that the paintings that had returned from Paris but were retained in Brussels, would actually come to Antwerp. The stained glass windows show the patron saints of the donators. The left window was made by Jean-Baptiste Bethune in 1864, the central and the right one by the workshop of August Stalins and Alfons Janssens in 1889-1890.

Formerly the Four Holy Crowned Ones of the masons, stonedressers and slaters

From 1389 this chapel housed the precious Circumcision relic, until the new Circumcision guild, founded in 1427, soon moved it to the next chapel.

The wall painting with the Calvary reminds us of the Confraternity of the Holy Cross, which shared the altar here until 1492. The location of these two devotions of the passion is not co-incidental since the warm southern side of the church is symbolic of Jesus’s full love, preparatory to the total sacrifice of His life. Because the services for the Old Longbow guild took place here until 1476, their patron saint, Sebastian, is standing by this Calvary.

The wall painting with the escutcheon of the Bode family underneath, refers to the murder of bailiff Jan Bode in 1389. Between the next of kin of the victim and the murderers a reconciliation deal was made, which was ritually concluded with a kiss. The murderers, Jan and Nicolaas van Wyneghem and Jan Winken, were obliged to found an everlasting mass for Jan Bode’s salvation.

Afterwards the chapel only belonged to the guild of the masons, stonedressers and slaters, namely an important part of the building industry. Their patron saints were the Four Holy Crowned Ones: four Roman martyrs who exercised the profession themselves. The altar triptych with Their work, their refusal to make an idol and their sentence, a work by Frans II Francken from 1598, is now in KMSKA (Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp).

The lack of occupancy after the French Revolutionary Rule since 1798, ended in 1868, when the chapel was devoted to Louis Frarijn, alias Ludovicus Flores, who had just been beatified by pope Pius IX. On the altar there is a large reliquary, which looks very much like a Gothic church building. On the stained glass windows, made by Henri Dobbelaere in 1868, after a design by Louis Hendrickx, saints have been represented who mainly have a link with Antwerp or with the then archdioceseThe most important diocese within a church province. In the Belgian Church Province, this is the Diocese of Mechelen-Brussels. An archbishop governs an archdiocese..

On the left and right windows are missionaries who brought Jesus’s gospel to Antwerp. Above them there are coats of arms that are related to their birthplace or their origin, below them are the escutcheons of the place where they died. On the left window: Saint Eligius, Saint Dymphna and Saint Amandus. On the right one: Saint Willibrord, Saint Walpurga and Saint Norbert. In the central window are martyrs of faith, who in their turn carried the Christian faith from their own Flemish homeland to other places. With them the coats of arms of the places of their birth and death are underneath, whereas above them are the arms of their own religious orderOrganisation of unmarried women or men who want to live in community to devote themselves to religious life. They follow the rule of their founder: e.g., Augustine, Benedict, Norbert, Francis, Dominic, Ignatius, … When joining the Order, members take three vows: obedience (to the superior), poverty (no personal possessions) and purity (no physical relationship).. In the middle is the Antwerpian Ludovicus Flores, who had just been beatified. He lived with his parents in Wolstraat (Wool Street) for a few years but they emigrated to Mexico via Spain. He entered the order of the Dominicans and around 1609 he was sent to the Philippines as a missionary. In 1620 he set off for Japan, where Christians were fiercely persecuted. On the way his ship was captured by Dutch pirates, who delivered him up to the Japanese. Together with many others he died a martyr at the stake near Nagasaki on 20 August 1622. This explains why in the stained glass window we can see firewood behind him and the palm in his hand, sign of heavenly victory in martyrdom.

The stone statue of Frarijn, by Jan-Baptist De Boeck and Jan-Baptist Van Wint, also dates from 1868. A street name on the Left Bank honours this eventful Antwerpian. He is flanked by the Jesuit Saint John Berchmans from Diest and the Friar Minor from the Brussels area, Saint Francis of Rode, one of the nineteen Martyrs of Gorkum († 1572). On the scroll of parchment are the names of those who shared his sad fate. In 1819 the painting that served as funeral a monument for the Plantin family was put here, as closely as possible to its original position in the ambulatory.

Formerly Circumcision chapel,

Saint Gregory of the soap boilers,

Saint Ambrose of the schoolteachers

This space too was meant for prayer. In 1431 at the latest it housed the Circumcision guild and its precious city relic: Jesus’s foreskin (or what was passed for it). This may explain that one of the oldest mural paintings in the cathedral (first half 15th century), the legendary Mass of Saint Gregory, of which the most striking remainder is the Man of Sorrows, with an aureole that has been worked out in relief, is to be found here. During the consecration pope Gregory saw the suffering Christ, standing on the altar: a popular late Medieval EucharisticThis is the ritual that is the kernel of Mass, recalling what Jesus did the day before he died on the cross. On the evening of that day, Jesus celebrated the Jewish Passover with his disciples. After the meal, he took bread, broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat. This is my body.” Then he took the cup of wine, gave it to his disciples and said, “Drink from this. This is my blood.” Then Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” During the Eucharist, the priest repeats these words while breaking bread [in the form of a host] and holding up the chalice with wine. Through the connection between the broken bread and the “broken” Jesus on the cross, Jesus becomes tangibly present. At the same time, this event reminds us of the mission of every Christian: to be “broken bread” from which others can live. theme to emphasize that the sacred hostA portion of bread made of unleavened wheat flour that, according to Roman Catholic belief, becomes the body of Christ during the Eucharist. in the Eucharist really is ‘The Body of Christ’. The parallel with the Circumcision relic is obvious. Because of the city relic this was also the municipality’s chapel, but already in ca. 1497 they moved to the new, spacious ‘Circumcision chapel’ (the present Saint Antony’s chapel); the Circumcision guild and the relic followed some 15 years later.

Since the construction of the chapter sacristy behind it in 1482-1487, this could be entered through a narrow door on the right, until 1736, when it was replaced by the wide Baroque doorway (Cornelis Struyf) meant to enable them to set off ceremonially in a procession. Unfortunately the figure of Saint Gregory in prayer was definitively destroyed to this purpose. It is also regrettable – though not irreversible – that the little Medieval door was walled up again in 2014.

In 1497 the chapel was used by Saint Gregory’s guild of the soap boilers, who came from the Venerable chapel. The presence of the older painting of Saint Gregory was probably not foreign to this choice. From then on the altar and the chapel were known by the name of Saint Gregory, while the decorative leather bucket stencils that were glued to the wall (but have now been hidden again under whitewash) illustrated the professional activities of the soap boilers. In 1585 they received company of the schoolteachers’ guild, which soon resulted in a new, joint altar triptych by Frans I Francken.

The stained glass window, designed by Pieter van der Ouderaa and executed by August Stalins and Alphonse Janssens in 1881, was a present of the Geelhand family to commemorate canon Christiaan Geelhand († 1731). Underneath the traditional name saints, Saint Christian and Saint Louis, his motto is ‘Animo et Fortitudine’ (inspired and strengthened). The marble cenotaph of bishop Ambrose Capello was originally in the sanctuary.

Because since 1803 the former chapter sacristy has mainly been used as the large sacristy for the side altars in the ambulatory and especially for the parish altar (the high altar and since ca. 1960 the crossingThe central point of a church with a cruciform floor plan. The crossing is the intersection between the longitudinal axis [the choir and the nave] and the transverse axis [the transept]. altar) this former choir chapelA chapel along one of the straight side walls of the choir. is the only one that has not received its original function back, but only functions as a passageway to the sacristy.

Formerly Saint Barbara

The small door to the adjacent service building has been preserved here. From ca. 1487 it gave access to the chapter library, and presumably from 1592 to the chapter house. In 1661 the chapel was taken into use by the newly founded confraternity of Saint Barbara, who commissioned Thomas Willebrord-Bosschaert to copy a painting by Antony van Dijck: Christ at the cross (Dendermonde, Our Lady’s Church).

The only noteworthy 19th century event was the renewal of the stained glass window by the Stalins-Janssens workshop in 1891. With it the Gife children wanted to honour their father, Eugene Ludovic Gife, who lead the restoration works at Our Lady’s Church for 25 years, and his wife, Hendrika Isabella Nuijens. By executing the six name saints in 15th century style and in bright, yellow brown pastel colours, they wanted to avoid disturbing Rubens’s colourful triptych The ResurrectionThis is the core of the Christian faith, namely that Jesus rose from the grave on the third day after his death on the cross and lives on. This is celebrated at Easter. (funeral monument for Jan Moretus and Martina Plantin) as much as possible with the incident light of the (normally multi-coloured) stained glass window.

The refurbishing, including the new altar, was the present of parishioners in honour of the golden anniversary of the ordination of Mgr. Frans Cleynhens, resigning parish priest of Our Lady’s parish and dean of Antwerp (1921). He widened the tribute to his person to the soldiers of the parish who died in the First World War. He could not attend the consecration of the chapel however. In 1922, only half a year after his resignation, he died.

On the altar painting Our Lady of Peace (Jozef Janssen, 1924) Mary and Child are enthroned in the sanctuary of the church, where the high altar is standing in its then form. In front of them King Albert, in military uniform, is on his knees, while Jesus offers him peace with an olive branch. Queen Elizabeth, who is wearing a nurse’s uniform of the Red Cross and attending to a wounded soldier, may be seen as a suggestive echo of war propaganda. Still this representation indicates that she often visited wounded soldiers and that she stimulated the popularity of the Belgian Red Cross. Both sovereigns are backed up by their respective patron saints, Albert of Louvain and Elizabeth. On Mary’s right hand side is Mgr. Cleynhens, whose jubilee is being celebrated, and on her left CardinalIn the Roman Catholic Church, a cardinal is a member of the pope’s council and thus he has an important advisory role. Up to the age of eighty, the cardinals also elect the new pope. Most cardinals are also bishops, but this is not a requirement. ArchbishopThe bishop in charge of the archdiocese. In actual practice, this also means that he is the head of the church province. Mercier. In his hand he has the famous pastoral letter from ChristmasThe feast commemorating the birth of Jesus. It is always celebrated on December 25. 1914, in which he fiercely denounced the German aggression, random executions of civilians and destructions, and on the other hand praised true patriotism. On the marble throne one can read the invocation ‘Regina Pacis OPN’ (Queen of Peace, pray for us), the title that pope Benedict XIV granted to Mary during the First World War. The five small scenes on the predella give images of war events in as many cities. In the middle is Antwerp, surrounded by towns that met with far heavier German shelling. From East to West: Dinant, Louvain, Ypres and Nieuwpoort.

During the opening ceremony of the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp, which was partly held in the cathedral, Cardinal Mercier’s speech was highly acclaimed in the press. A journalist summarized it as follows: Before 1914 sports were a means to prepare for war. […] But now they serve as a preparation for peace. […] They serve as social training, […] they teach self-control and discipline, gallantry and pride. […] we must be convinced of the social meaning of sports, which do not only steel our muscles and strengthen us, but also contribute to improve our beings.

The bronze plaque against the wall honours each of the 45 parishioners who died in battle. In this way the Cardinal’s call was answered: it was his express wish to continue cherishing their sacrifice of love for our freedom. Thinking of the Americans who arrived in Antwerp by boat – only a stone’s throw from here – Mercier personally had a plaque put in this church: to thank the United States for the strong help they had rendered including food supply. In 1927, at the entrance of this church the British put up a memorial for the soldiers of the British Commonwealth who died in battle – as they did in some thirty French and Belgian cathedrals.

The small door to the adjacent service building has been preserved here. From ca. 1487 it gave access to the chapter library, and presumably from 1592 to the chapter house. In 1661 the chapel was taken into use by the newly founded confraternity of Saint Barbara, who commissioned Thomas Willebrord-Bosschaert to copy a painting by Antony van Dijck: Christ at the cross (Dendermonde, Our Lady’s Church).

The only noteworthy 19th century event was the renewal of the stained glass window by the Stalins-Janssens workshop in 1891. With it the Gife children wanted to honour their father, Eugene Ludovic Gife, who lead the restoration works at Our Lady’s Church for 25 years, and his wife, Hendrika Isabella Nuijens. By executing the six name saints in 15th century style and in bright, yellow brown pastel colours, they wanted to avoid disturbing Rubens’s colourful triptych The Resurrection (funeral monument for Jan Moretus and Martina Plantin – p. 92) as much as possible with the incident light of the (normally multi-coloured) stained glass window.

The refurbishing, including the new altar, was the present of parishioners in honour of the golden anniversary of the ordination of Mgr. Frans Cleynhens, resigning parish priest of Our Lady’s parish and dean of Antwerp (1921). He widened the tribute to his person to the soldiers of the parish who died in the First World War. He could not attend the consecration of the chapel however. In 1922, only half a year after his resignation, he died.

On the altar painting Our Lady of Peace (Jozef Janssen, 1924) Mary and Child are enthroned in the sanctuary of the church, where the high altar is standing in its then form. In front of them King Albert, in military uniform, is on his knees, while Jesus offers him peace with an olive branch. Queen Elizabeth, who is wearing a nurse’s uniform of the Red Cross and attending to a wounded soldier, may be seen as a suggestive echo of war propaganda. Still this representation indicates that she often visited wounded soldiers and that she stimulated the popularity of the Belgian Red Cross. Both sovereigns are backed up by their respective patron saints, Albert of Louvain and Elizabeth. On Mary’s right hand side is Mgr. Cleynhens, whose jubilee is being celebrated, and on her left Cardinal Archbishop Mercier. In his hand he has the famous pastoral letter from Christmas 1914, in which he fiercely denounced the German aggression, random executions of civilians and destructions, and on the other hand praised true patriotism. On the marble throne one can read the invocation ‘Regina Pacis OPN’ (Queen of Peace, pray for us), the title that pope Benedict XIV granted to Mary during the First World War. The five small scenes on the predella give images of war events in as many cities. In the middle is Antwerp, surrounded by towns that met with far heavier German shelling. From East to West: Dinant, Louvain, Ypres and Nieuwpoort.

During the opening ceremony of the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp, which was partly held in the cathedral, Cardinal Mercier’s speech was highly acclaimed in the press. A journalist summarized it as follows: Before 1914 sports were a means to prepare for war. […] But now they serve as a preparation for peace. […] They serve as social training, […] they teach self-control and discipline, gallantry and pride. […] we must be convinced of the social meaning of sports, which do not only steel our muscles and strengthen us, but also contribute to improve our beings.

The bronze plaque against the wall honours each of the 45 parishioners who died in battle. In this way the Cardinal’s call was answered: it was his express wish to continue cherishing their sacrifice of love for our freedom. Thinking of the Americans who arrived in Antwerp by boat – only a stone’s throw from here – Mercier personally had a plaque put in this church: to thank the United States for the strong help they had rendered including food supply. In 1927, at the entrance of this church the British put up a memorial for the soldiers of the British Commonwealth who died in battle – as they did in some thirty French and Belgian cathedrals.

The small door to the adjacent service building has been preserved here. From ca. 1487 it gave access to the chapter library, and presumably from 1592 to the chapter house. In 1661 the chapel was taken into use by the newly founded confraternity of Saint Barbara, who commissioned Thomas Willebrord-Bosschaert to copy a painting by Antony van Dijck: Christ at the cross (Dendermonde, Our Lady’s Church).

The only noteworthy 19th century event was the renewal of the stained glass window by the Stalins-Janssens workshop in 1891. With it the Gife children wanted to honour their father, Eugene Ludovic Gife, who lead the restoration works at Our Lady’s Church for 25 years, and his wife, Hendrika Isabella Nuijens. By executing the six name saints in 15th century style and in bright, yellow brown pastel colours, they wanted to avoid disturbing Rubens’s colourful triptych The Resurrection (funeral monument for Jan Moretus and Martina Plantin – p. 92) as much as possible with the incident light of the (normally multi-coloured) stained glass window.

The refurbishing, including the new altar, was the present of parishioners in honour of the golden anniversary of the ordination of Mgr. Frans Cleynhens, resigning parish priest of Our Lady’s parish and dean of Antwerp (1921). He widened the tribute to his person to the soldiers of the parish who died in the First World War. He could not attend the consecration of the chapel however. In 1922, only half a year after his resignation, he died.

On the altar painting Our Lady of Peace (Jozef Janssen, 1924) Mary and Child are enthroned in the sanctuary of the church, where the high altar is standing in its then form. In front of them King Albert, in military uniform, is on his knees, while Jesus offers him peace with an olive branch. Queen Elizabeth, who is wearing a nurse’s uniform of the Red Cross and attending to a wounded soldier, may be seen as a suggestive echo of war propaganda. Still this representation indicates that she often visited wounded soldiers and that she stimulated the popularity of the Belgian Red Cross. Both sovereigns are backed up by their respective patron saints, Albert of Louvain and Elizabeth. On Mary’s right hand side is Mgr. Cleynhens, whose jubilee is being celebrated, and on her left Cardinal Archbishop Mercier. In his hand he has the famous pastoral letter from Christmas 1914, in which he fiercely denounced the German aggression, random executions of civilians and destructions, and on the other hand praised true patriotism. On the marble throne one can read the invocation ‘Regina Pacis OPN’ (Queen of Peace, pray for us), the title that pope Benedict XIV granted to Mary during the First World War. The five small scenes on the predella give images of war events in as many cities. In the middle is Antwerp, surrounded by towns that met with far heavier German shelling. From East to West: Dinant, Louvain, Ypres and Nieuwpoort.

During the opening ceremony of the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp, which was partly held in the cathedral, Cardinal Mercier’s speech was highly acclaimed in the press. A journalist summarized it as follows: Before 1914 sports were a means to prepare for war. […] But now they serve as a preparation for peace. […] They serve as social training, […] they teach self-control and discipline, gallantry and pride. […] we must be convinced of the social meaning of sports, which do not only steel our muscles and strengthen us, but also contribute to improve our beings.

The bronze plaque against the wall honours each of the 45 parishioners who died in battle. In this way the Cardinal’s call was answered: it was his express wish to continue cherishing their sacrifice of love for our freedom. Thinking of the Americans who arrived in Antwerp by boat – only a stone’s throw from here – Mercier personally had a plaque put in this church: to thank the United States for the strong help they had rendered including food supply. In 1927, at the entrance of this church the British put up a memorial for the soldiers of the British Commonwealth who died in battle – as they did in some thirty French and Belgian cathedrals.

Formerly Saint Boniface of the tailors

The keystone with singing angels only dates back to about the middle of the 15th century, but about the earliest users of the chapel nothing is known. In ca. 1630 Artus Wolfort painted The adoration of the Magi for the altar in the tailors’ Saint Boniface’s chapel. After the French Revolutionary Rule the painting ended up in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts via the local museum of the academy.

In 1825 parish priest, and later Cardinal and Archbishop, Engelbert Sterckx founded the first confraternity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Belgium. The altar, after a design by Francois Durlet (1844), was the first neo-Gothic realisation in the cathedral and one of the first ones in Antwerp. The polychrome retable statue of the Sacred Heart, added by Frans De Vriendt in 1874, typifies the sternly linear, spiritless ecclesiastical neo-Gothic. It is quite bizarre that of all statues, the one that focuses so much on Jesus’s bondless love, does not show the single trace of warm-heartedness. At that time church art was far too much used for the benefit of dogmatic abstractions. Christ is flanked by Francis de Sales and John, the only evangelist who mentions that water and blood came out of the wound when Jesus’s heart was pierced (John 19:33).

On the opposite wall is the painting The apparition of Christ to Saint Margaret Mary Alaqoque (Corneel Seghers, ca. 1844). In 1673-1675 this nunFemale member of a religious order saw an apparition of Christ, who showed her his heart, in her convent in Paray-le-Monial.

Although it is only visible as the side wound, Jesus’s pierced heart is central in the stained glass window The devotion to the Sacred Heart finds its origin in Jesus’s crucifixion (Edouard Didron, 1872), in which some thirty saints from all times are gathered around the lamentation of the dead Christ.