The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

Our Lady's Spire

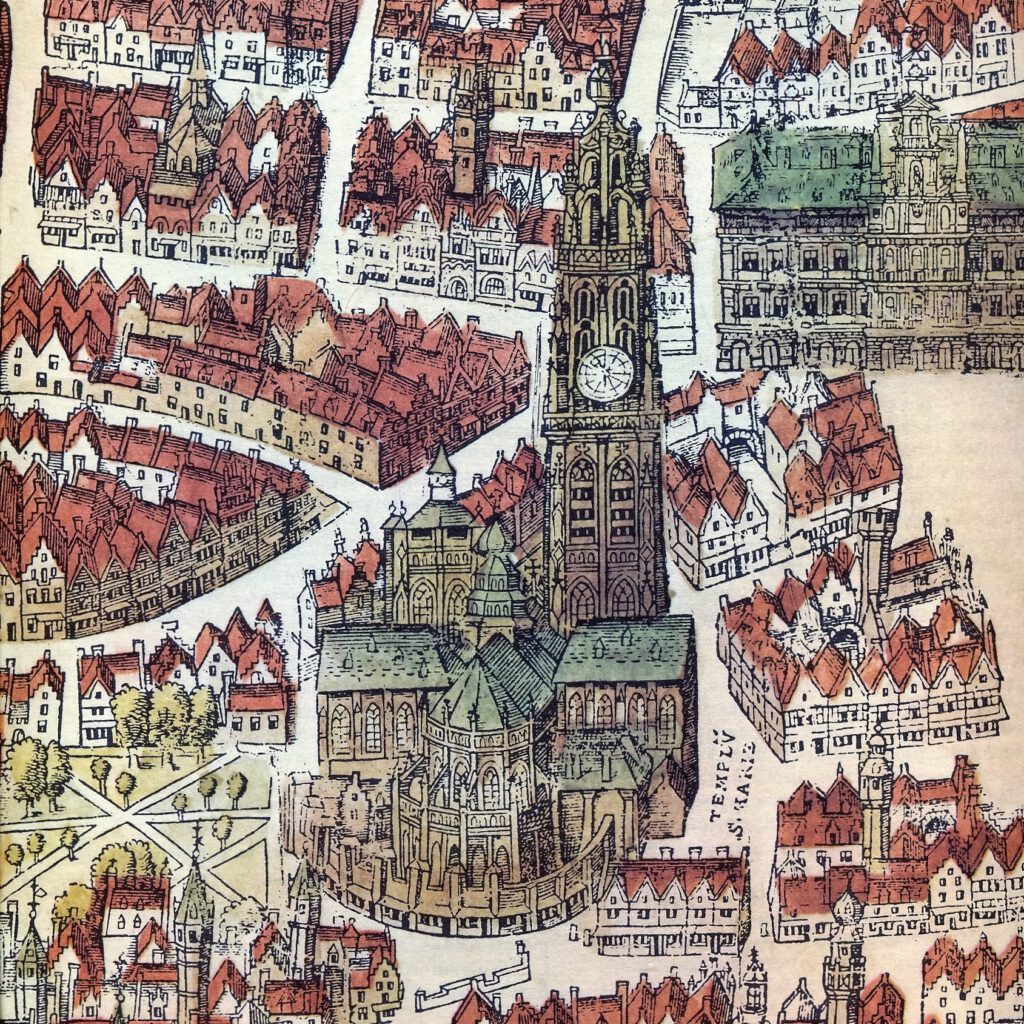

What makes Antwerp cathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is. unique is its elegant 123m (403ft.) tall tower, which draws everybody’s attention: the symbol of the city that all Antwerpians are proud of. In the flat landscape this spire can be seen from miles around. In former times, when everybody shared the same Catholic belief and the urban skyline did not know any competitive or obscuring high-rise blocks, Our Lady’s spire was the religious orientation point in the wide vicinity.

Once you come closer you can have a better view from alongside: from Oude Koornmarkt, the corner of Pelgrimstraat or Tempelstraat, or from Korte and Lange Ridderstraat. It is extremely fascinating to see the different colours of this tower following the changing incidence of sunlight.

For people on the road the tower in the landscape is a signpost to their destination. But even more this tower is a signpost for those who are on the road in their lives to their final destination. The spire points to Heaven, which is the symbol of the transcendence of God, ‘the Most High’. Without any doubt at the same time the pride of the urban community plays its part, since the most important church tower is also the belfry, which used to be the custom in the duchy of Brabant. This explains why Our Lady’s spire is still city property and as a consequence from ground level it cannot be entered but by the stairs tower, which only gives out onto the street.

There are only few towers that embody the ideal of a Gothic tower so strongly as the Antwerp Our Lady’s spire does. What makes this tower so unique is the elegance with which it rises high above the sea of houses. Most church towers in these regions have a square base made of stone, on which a wooden spire has been put. The result is a quite abrupt transition. Here the unstoppable upward movement is so gradual that one hardly notices the structure of the edifice. Slowly but surely this tower becomes more slimline and finer. From a robust square base of ca. 144 m² (1,550 ft².) the colossus rises, foot by foot, nearly unnoticed to one single point of only a few cm² that touches Heaven. The Art of a Tower. This is why only few artists manage to paint this subtle dynamism perfectly.

From ground level in Oude Koornmarkt this gradual rise, section by section, can be contemplated quietly. The wall at the bottom is still extremely sturdy: a nearly rough massThe liturgical celebration in which the Eucharist is central. It consists of two main parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The main parts of the Liturgy of the Word are the prayers for mercy, the Bible readings, and the homily. The Liturgy of the Eucharist begins with the offertory, whereby bread and wine are placed on the altar. This is followed by the Eucharistic Prayer, during which the praise of God is sung, and the consecration takes place. Fixed elements are also the praying of the Our Father and a wish for peace, and so one can symbolically sit down at the table with Jesus during Communion. Mass ends with a mission (the Latin missa, from which ‘Mass’ has been derived): the instruction to go out into the world in the same spirit. of stone. Each time the width of the cubic content of the next section has been shrunk with some ten centimetres (four inches), which has a diminishing exponential effect on the surface area. In the second and following sections, also in the Southern tower, merely decorative structures of glassless windows have been fitted into the actual walls of the tower between the buttresses. This causes a more lively and lighter effect. The richer decoration at the window of the second section already makes it airy. From the fourth section of the Northern tower there are no blind walls behind the windows: they constitute the belfry windows for the heavy chiming bells. The more the tower rises higher, the more not only does the heavy base with its enormous buttresses narrow but also the walls have been exploded more and more and also been worked out more decoratively. The most brusque switch is this from the fourth to the fifth section: from a square base to a narrower, octagonal drum. Because the sides of the octagon are not parallel with the sides of the square base, the drum gives the illusion of being roundish. This effect is also caused by the fact that when looked at from the front the drum shows two sides, which, due to the absence of a compact mass of stone, are not perceived as the sides of a polygon. Each of the eight sides only consists of two open window structures one above the other, which let the sound of the smaller carillon bells out. Because the drum has been twisted with respect to the square base it also stands freer. Also the accentuated but airily worked open balustrade contributes to this because it blurs the attachment of both volumes. Yet the heavy buttresses of the square base evolve into the enormous tall, slender pinnacles, which shoot as it were through the balustrade. Even though their presence was meant constructionally in the first place, to exert pressure on the corners that have to absorb the pressure of the octagon, they wreathe about the drum decoratively, which is no less important. Because they are as tall as the drum one does not see immediately that the square is becoming circular. And because they allow one to see the sky they cause an extra airy effect. The circular character is confirmed by the balustrade on the octagonal drum, which seems to be hexadecagonal due to the pilasters that divide each side equally. Finally the central stairs shaft rises surrounded by crosswise positioned pinnacles and on top it is nothing but sculpture. It is not for nothing that this natural stone tower is described as ‘stone lacework’: so exquisitely elegant and so richly decorated are the sculptured elements of the tracery, pinnacles and balustrades, which increase in volume proportionally with the height of the tower. Proper to what happened in the beginning of the 16th century, Renaissance enters into Gothic architecture as decorative morphology, which can be seen in the top – unobtrusively – in half arches and twisted octagonal columns. It is nearly incredible how such a massive tower base can receive such rising impetus and is finally absorbed into thin air: a tower that shoves off from the ground as a gigantic rocket on its way to Heaven. Please do not look for some hidden symbolism, let alone magical powers, in the number 123. The builders never knew a height of 123 metres, as they counted in Antwerp feet, which means that for them the tower was approximately 430 feet tall.

It took nearly a century to build the tower. The wooden crane which has been in the Southern tower since 1533 gives an idea of the labour-intensive way of construction, in which labourers patiently hoisted up beam after beam, heap of stones after heap of stones. It consists of a wheel in which one or two workers trod to make it move. In the middle there is an axle around which a rope is wound that goes over a pulley on the highest level (of each stage of the construction).

The official date of finishing the tower is the consecrationIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words. of the tower cross by Adriaen Aernout, auxiliary bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’. of Cambrai. Anno 1518. September 1st. Then the tower or Our Lady was completed, and the cross, which had first been christened and anointed, was put on to the tower and they danced around this cross on the scaffold that had been made around it, for everybody to be seen. The ‘highest’ dancing party ever in Antwerp!

The Antwerpians are not sad that the second tower could never reach the same height, since the one completed tower looks more elegant. The reason why this second tower was never finished, has to do with the audacious dream of the ‘New Work’.

In a laudatory poem of over 500 verses (1723) the poet and monkA male member of a monastic order who concentrates on a life of balance between prayer and work in the seclusion of a monastery or abbey. Godefridus Bouvaert expresses how much the tower and the city are linked to each other inseparably.:

Sweet city full of art, preferred by every power!

In all that I possess there is not one such tower;

That in Strasbourg, it is not so ingenious

Though quite as tall or slightly taller is its truss.

In Europe ‘t would be even more subject of talks

If this rich jewel had been hidden in a box

And if people coming from everywhere

Could only see the tower once a year.

And if making too many debts did not withhold

Me, or, if I could, I had it covered with gold.

And still it would be too little, and gold too poor,

Art deserves quite more and demands better amour.

Antwerp, please, preserve this jewel evermore,

Whose building lasted a hundred years minus four,

Drop everything you wish like a wielded flower,

The town will be great with the standing Tower.

The weather cock and the chiming bells

On top of the cathedral tower there is a proud gilded weathercock. In the first place it is a weathervane, but symbolically it is also an alarm clock. Together with the bells it incites the believers to come to church. The oldest city bell – also the alarm bell – Orida (‘the Terrible one’, 1316), which used to be in the Romanesque church tower, can be admired in the Vleeshuis Museum ‘The sound of the city’. From the chiming bells that are still there Gabriel (1459) is the oldest one. The largest one, Carolus (1507), called after prince and later emperor Charles V, was the alarm bell and now rings at grand festivities. In times without engines no less than 16 men, spread over four storeys, were needed to chime this colossus, which weighs nearly six tons. When the carillon plays, even in the roaring city, you can experience how strongly the cathedral remains the soul of its vicinity.