The Our Lady’s Cathedral of Antwerp, a revelation.

The bishop's church

A bishop’s church only distinguishes itself from all other churches by a piece of furniture: the bishop’s seat or cathedra. This explains why a bishop’s church is also concisely named after it: a ‘cathedral’. On the back of the cathedra is the escutcheon of the present bishopPriest in charge of a diocese. See also ‘archbishop’..

In the sacristyThe room where the priest(s), the prayer leader(s) and the altar server(s) and/or acolyte(s) prepare and change clothes for Mass. there is a series of portraits of the Antwerp bishops. They represent ‘apostolic succession’, with which their authority and its legality are emphasized, which results from the uninterrupted succession in episcopacy. It can be noticed that they too were subjected to fashionable features, such as the long wigs from the middle of the 18th century, and the pride with which two of them had their valuable watches depicted as well. The 17th bishop, Jacobus Thomas Wellens, lets himself be led by Death, which incites him to be generous to a mother and her child in need: an allusion to his commitment for poor relief. Just next to the entrance to this sacristy there is the painting Episcopal consecrationIn the Roman Catholic Church, the moment when, during the Eucharist, the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus, the so-called transubstantiation, by the pronouncement of the sacramental words. of Godfried van Mierlo o.p. as bishop of Haarlem, which took place in this church in 1571. The bishops are privileged to be buried in a tomb underneath the sanctuary. Their bones however were stolen by the French Revolutionaries. One bishop, Franciscus d’Espinosa, a Capuchin monkA male member of a monastic order who concentrates on a life of balance between prayer and work in the seclusion of a monastery or abbey., preferred to be buried with all simplicity among the common people in the Green Graveyard in 1742. In 1840, when the foundations for Rubens’s statue were made in Groenplaats, his tomb was discovered.

The tomb of bishop

Marius Ambrosius Capello

(Artus II Quellinus, before 1676)

In the Baroque period the bishops had a set of tombs constructed in the sanctuary. The fifth and last monument was this of Msgr. Capello, the seventh bishop of Antwerp (1652-†1676), which was situated in the southern part of the sanctuary. At his birth, in Antwerp, his Italian parents gave him ‘Marius’ as baptismal name, while when entering the Dominican order he received the monastic name ‘Ambrosius’. Due to its exceptional sculptural quality Capello’s tomb was the only one that was not destroyed by the French Revolutionaries, but it was preserved for the École Centrale. Fortunately it returned to the cathedralThe main church of a diocese, where the bishop’s seat is., but because of its present position at the entrance to the sacristy, which brought about a totally different orientation, its original context became completely lost. On top of the red veined sarcophagus the bishop lies outstretched full length, in his episcopal vestments. The bishop’s crozier next to him has gone missing, but a putto still functions as a shield bearer of Capello’s escutcheon. With the upper part of his body raised, attentively looking up in the direction of the high altarThe altar is the central piece of furniture used in the Eucharist. Originally, an altar used to be a sacrificial table. This fits in with the theological view that Jesus sacrificed himself, through his death on the cross, to redeem mankind, as symbolically depicted in the painting “The Adoration of the Lamb” by the Van Eyck brothers. In modern times the altar is often described as “the table of the Lord”. Here the altar refers to the table at which Jesus and his disciples were seated at the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper. Just as Jesus and his disciples did then, the priest and the faithful gather around this table with bread and wine. and his hand folded in prayer, the bishop kept on assisting at the religious rites: the Baroque theme of the so-called perpetual adoration. Moreover he contemplated the hopeful perspective of Mary’s assumption, as it had been painted by Rubens.

With his long curly hair, his delineated moustache and goatee the portrayed person follows the gentlemen’s fashion of his day. It is astonishing how naturalistic the sculptor, Artus II Quellinus, renders the material: the full cheeks, the double chin and the bony veined hands are nearly physical. The imitation of tissues is nicely varied, from the extremely fine lace at the collar and the sleeves, the meticulously pleated rochetA long-sleeved, half-length white robe worn over a cassock. Rochet is a synonym. till the embroidered paraments of the cope with a buckle and the high mitreThe ceremonial headgear of bishops and abbots. The front and back are identical pentagons pointing upwards.. True to nature the cushion also gives way under the pressure of his left arm.

On the cope there are scenes from the life of SaintThis is a title that the Church bestows on a deceased person who has lived a particularly righteous and faithful life. In the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church, saints may be venerated (not worshipped). Several saints are also martyrs. Marius, who in Italy is better known by the popular Christian name ‘Mario’, after whom Capello was named at his baptismThrough this sacrament, a person becomes a member of the Church community of faith. The core of the event is a ritual washing, which is usually limited to sprinkling the head with water. Traditionally baptism is administered by a priest, but nowadays it is often also done by a deacon.. In the days of emperor Claudius (268-260 AD) Marius and his family travelled from Persia to Rome to venerate the apostle’s tombs. First of all they took care of the imprisoned Christians. Afterwards Marius sought contact with the free, persecuted Christians. During the night he was attracted by their singing of psalms and knocked at their door. As they were afraid of the civic guard the Portuense Christian community dared not open it, but Callistus, their bishop, told them it was Christ himself who was knocking at their door. On the relief at Capello’s right shoulder Marius greets with his hat politely in his hand. The bishop opens the door – detailed with a lock and hinges – to him only suspiciously ajar but also indicates him as the ‘Christ’. This ‘embroidered medallion’ is also to be found on the cope of Saint Gregory on the triumphant high altar that Capello gave as a present to Saint Paul’s, the church of his order, and which was made by Peter I and II Verbruggen (1670). In the relief on top of his right shoulder Marius unflinchingly testifies of his Christian faith in front of the emperor. In the scene underneath he is taken to prison. In the undermost relief Marius is talking to a man (?). Because of his religious testimony and his commitment for the persecuted Christians Marius is finally tortured, in the relief bottom left. While two men keep Marius’s head in check, one of his feet is chopped off with an axe. It is remarkable that there is not a single scene in which Marius’s wife Martha or their two sons, Audifax and Abachus, are also depicted. A concession to the celibate bishop?

- Our Lady’s Cathedral

- History & Description

- Preface

- Introduction

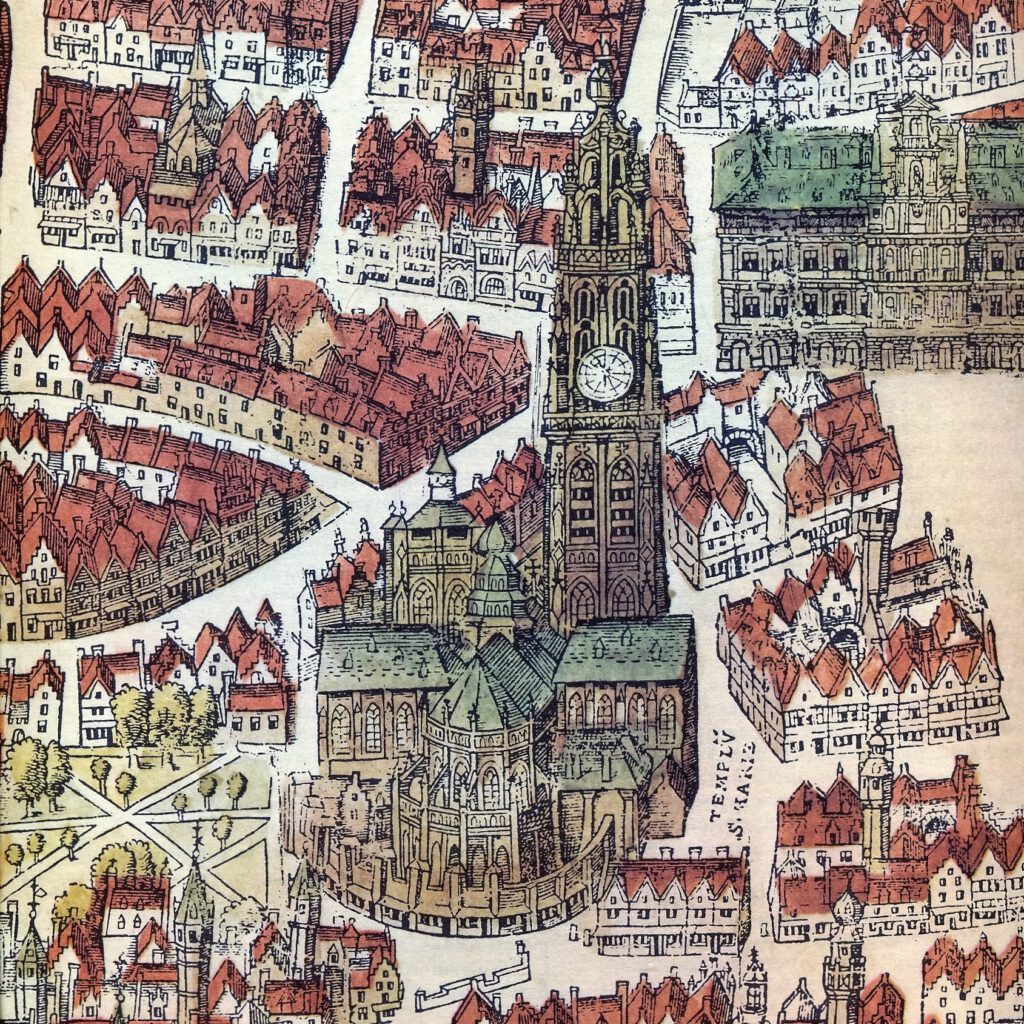

- Historical context

- A centuries-long building history

- A cathedral never stands alone

- Our Lady’s spire

- The main portal

- Spatial effect

- Mary’s Assumption (C.Schut)

- Erection of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- Descent of the Cross (PP.Rubens)

- The Resurrection (PP.Rubens)

- Mary’s Assumption (PP.Rubens)

- The high altar

- The collegial choir

- The bishop’s church

- The parish church

- The pulpit

- The confessionals

- Caring for the poor

- The Venerable chapel

- Mary’s chapel

- Corporations and guilds

- The ambulatory

- Funeral monuments

- Praise the Lord!

- Pull all stops: the organs

- Cross-bearer (J.Fabre)

- Bibliography